Kinship systems

A complex kinship system is a feature of Aboriginal social organisation across Central Australia. It determines how people relate to each other and their social, ceremonial and land-related roles, rights, responsibilities and obligations. For example, the kinship system determines suitable marriage partners, roles at funerals, everyday behaviour patterns and traditional land ownership groupings.

Today there are increasing numbers of ‘wrong skin’ marriages, in which people who would traditionally be prevented from marrying become partners. A result is families attempting to accommodate the contradictions this presents for the kinship system and wider relationships. Other rules of the system are more strongly enduring, such as avoidance relationships, especially that between mother-in-law and son-in-law. This applies through marriage but also in a classificatory sense within the kinship system, whereby the woman and man concerned are ‘classified’ as these in-laws by virtue of their membership in the relevant kinship categories. This in-law relationship requires a social distance, such that whole categories of people are not permitted in the same room or car, for instance. It is important to be sensitive to the signals or code for the rule, such as being told there is no space in the car or room even though there appears to be sufficient space.

Aspects of this system of social organisation differ between regions, namely in the division of society into so-called ‘skins’, named categories related to each other in prescribed ways through the kinship system. Yet there are more similarities than differences.

A moiety system (i.e. division into two groups: ‘sun side’ and ‘shade side’) exists across the region. Within this, most language groups also adhere to a section or subsection system with four to eight ‘skins’ or ‘skin names’, skins being Aboriginal English for the sections/subsections. An individual gains a skin name upon birth based on, but not the same as, his or her father. He/she automatically and permanently becomes a member of that section or subsection. Alternatively, the Pitjantjatjara language group, for example, is divided into moieties – ngana nt arka (literallty we-bone) ‘our side’, and tjanamilytjan (literally they flesh) ‘their side’ (Goddard 1996) – but don’t have sections or subsections so don’t use skin names, unless adopted for convenience from neighbouring language groups.

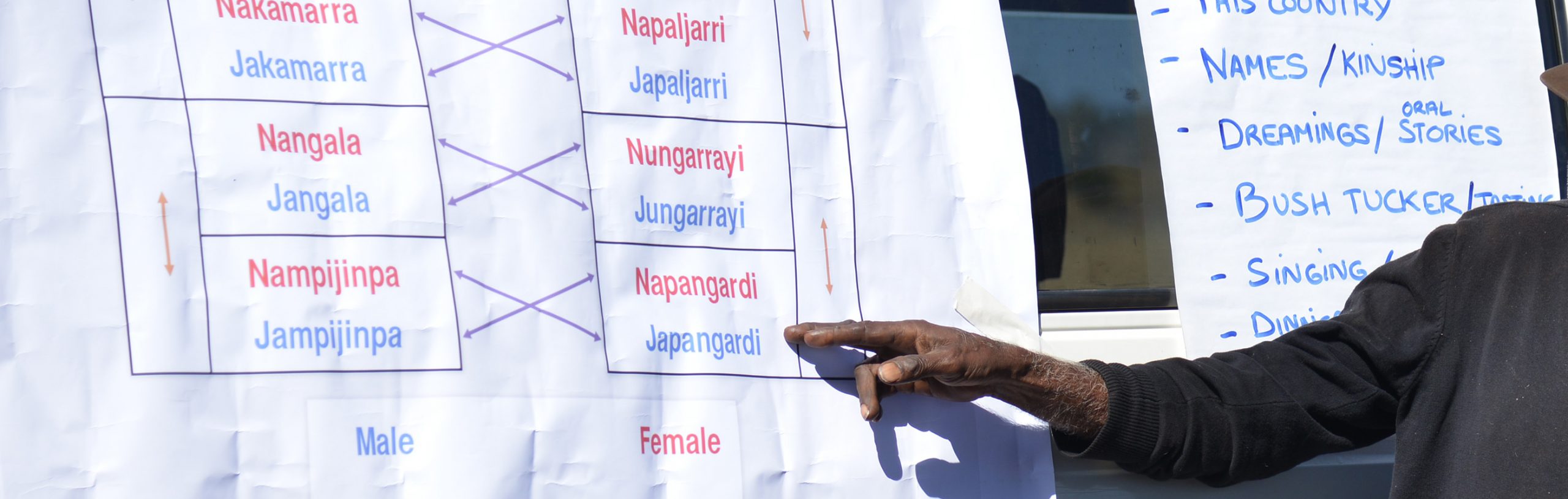

Skin names are spelled differently across the languages and dialects of central Australia, e.g. Warlpiri, Warumungu, Pintupi-Luritja and Pintupi, per the chart below.

This is largely because the languages have adopted different letters and letter combinations for writing particular sounds. It is best to keep to these spellings per language group.

Notice that the skin names starting with J (in Warlpiri) or Tj (in Western Desert dialects) denote males, and those starting with N denote females.

As well as their key part in social organisation, skin names can be used as personal identifiers, like a first name in English. With the person’s identity similarly fully understood by the context, skin names can be used to refer to someone who is absent.

Aboriginal people may have a number of names. For example, a person may have a European first name and surname, a bush name, a skin name and maybe even a nickname. Personal names are used less among relatives and community members than when the person is addressed by most non-Aboriginal people. Conversely, in some community organisations such as clinics, skin names have been frequently used like surnames. This can be a source of much confusion, heightened if a range of spellings are used.

Early contact relationships between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people were rather uncomfortable for the former since it was hitherto unheard of for a person not to be ‘something’ (i.e. not to have a skin classification, a firm social category). Thus Aboriginal people began to give non-Aboriginal people skin names. Some of the latter have taken this as a sign of acceptance, even particular fondness. It is truer to say that it is a mechanism Aboriginal people have employed to make their dealings with non-Aboriginals more comfortable, sometimes even favourable, for themselves. Here, Arrernte country singer Warren H Williams reflects on skin names given to non-Aboriginal people. Aboriginal people have generally come to understand non-Aboriginal people as relatively ‘free’ of kinship commitments of the kind that govern Aboriginal society. (Heffernan and Heffernan 1999:160)

Central Australian subsections or ‘skins’

| EASTERN/ CENTRAL ARRERNTE | KAYTETYE | EASTERN ANMATYERR | ALYAWARR | WARUMUNGU | WARLPIRI | PINTUPI LURITJA | PINTUPI | NGAANYATJARRA | |

| SKIN | Peltharre | Kapetye | Petyarr | Apetyarr | Purungu | ||||

| MALE | Tyapalye | Jappaljarri | Japaljarri | Tjapaltjarri | Tjapaltjarri | ||||

| FEMALE | Ngalyerre | Nappaljarri | Napaljarri | Napaltjarri | Napaltjarri | ||||

| SKIN | Pengarte | Pengarte | Pengart | ||||||

| MALE | Tyapeyarte | Jappangardi | Japangardi | Tjapangati | Tjapangati | ||||

| FEMALE | Ngampeyarte | Nappangardi | Napangardi | Napangardi | Napangardi | ||||

| SKIN | Kemarre | Kemarre | Kemarr | Akemarr | Karimarra | ||||

| MALE | Tyakerre | Jakkamarra | Jakamara | Tjakamarra | Tjakamarra | ||||

| FEMALE | Watyale | Nakkamrra | Nakamarra | Nakamarra | Nakamarra | ||||

| SKIN | Ampetyane | Ampetyane | Ampetyan | Milangka | |||||

| MALE | Mpetyakwerte | Jamin | Jampijinpa | Tjampijtinpa | Tjampijtinpa | ||||

| FEMALE | Tyamperlke | Nampin | Nampijinpa | Nampijtinpa | Nampijtinpa | ||||

| SKIN | Penangke | Penangke | Penangk | ||||||

| MALE | Tyaname | Jappanangka | Japanangka | Tjapanangka | Tjapanangka | ||||

| FEMALE | Ngamane | Nappanangka | Napanangka | Napanangka | Tjapanangka | ||||

| SKIN | Kngwarraye | Kngwarraye | Kngwarray | Kngwarrey | Tjarurru | ||||

| MALE | Tywekertaye | Jungarrayi | Jungarrayi | Tjungarrayi | Tjungarrayi | ||||

| FEMALE | Ngapete | Namikili | Nungarrayi | Nungarrayi | Nungarrayi | ||||

| SKIN | Perrurle | Pwerle | Pwerle | Apwerle | Panaka | ||||

| MALE | Tywelame | Jupurla | Jupurrula | Tjupurrula | Tjupurrula | ||||

| FEMALE | Ngamperle | Narurla | Napurrula | Napurrula | Napurrula | ||||

| SKIN | Angale | Thangale | Ngal | Yiparrka | |||||

| MALE | Tyangkarle | Jangala | Jangala | Tjangala | Tjangala | ||||

| FEMALE | Ngangkarle /Ngale | Nangala | Nangala | Nangala | Nangala |

Prepared by Inge Kral (2002) from Henderson and Dobson 1994:43; Heffernan and Heffernan 1999:159; Turpin 2000:121; Lizzie Ellis pers. comm.

References

- Breen, G. (2000) Introductory Dictionary of Western Arrernte. Alice Springs: IAD Press.

- Collins B. (1999) Learning Lessons: an independent review of Indigenous education in the Northern Territory. Darwin: NT Department of Education.

- Goddard, C. (1996) Pitjantjatjara/Yankunytjatjara to English Dictionary. Alice Springs: IAD Press.

- Green, J. (1984) A Learner’s Guide to Eastern and Central Arrernte. Alice Springs: IAD Press.

- Hale, K. (1995) An Elementary Warlpiri Dictionary. Alice Springs: IAD Press.

- Hansen, K.C. and L.E. (1992, 3rd Ed.) Pintupi/Luritja Dictionary. Alice Springs: IAD Press.

- Heffernan, J. and Heffernan, K. (1999) A Learner’s Guide to Pintupi-Luritja. Alice Springs: IAD Press.

- Henderson, J. and Dobson, V. (1994) Eastern and Central Arrernte to English Dictionary. Alice Springs: IAD Press.

- Hoogenraad, R. (2001) ‘Critical reflections on the history of bilingual education in Central Australia’ in J. Simpson, D. Nash, M. Laughren, P. Austin and B. Alpher (eds) Forty years on: Ken Hale and Australian Languages. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

- Hoogenraad, R. (2000) The history of Warlpiri education and literacy in the context of English and alphabetic writing. Unpublished manuscript.

- Hoogenraad, R. (1997) On writing and pronouncing Central Australian Aboriginal Languages. Unpublished manuscript.

- Hoogenraad, R and Thornley, B (2003) The jukurrpa pocket book of Aboriginal Languages of Central Australia and the places where they are spoken. IAD Press, Alice Springs.

- IAD Language Map (2002), Alice Springs.

- Kral, I. (2002) An Introduction to Indigenous Languages and Literacy in Central Australia Alice Springs: Central Australian Remote Health Development Services (CARHDS).

- Laughren, M., Hoogenraad, R., Hale, K., Granites, R.J. (1996) A Learner’s Guide to Warlpiri. Alice Springs: IAD Press.

- Nathan, P. and Leichleitner Japanangka, D. (1983) Settle Down Country – Pmere Arlaltyewele. CAAC: Kibble Books.

- Papunya School (2001) Papunya School Book of Country and History. Sydney : Allen and Unwin.

- Richardson, Nicholas (2001) Public Schooling in the Sandover River Region of Central Australia during the Twentieth Century – A critical historical survey. Unpublished Masters Thesis – Flinders University of South Australia.

- Turpin, M (2000) A Learner’s Guide to Kaytetye. Alice Springs: IAD Press.

- Yuendumu School Staff (2002) Yuendumu Two-Way Learning Policy 2002.