Category: News

Young leaders have been called upon to “keep our fire burning” as one of the country’s largest Aboriginal land councils celebrates five decades of fierce advocacy for land rights.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that this article may contain images and names of people who have died.

Thousands gathered at Alice Springs’ Telegraph Station on Saturday to mark 50 years of the Central Land Council, which today has 90 elected members representing more than 24,000 people in remote Central Australia.

CLC chair and Warlpiri man Warren Williams said the celebrations showed “the fire in our bellies still burns brightly, half a century on”.

“It’s very emotional because we get to remember some of our past delegates that have paved the way,” he said.

“There’s a lot of great achievements that have happened during [CLC’s history], getting our land rights back, our homes … people living on those homelands.

“50 per cent of the land that we’ve claimed is under [the] Land Rights Act, we’re still looking at some more.”

The CLC’s beginnings trace back to 1974, when elected leaders from around Central Australia gathered in Amoonguna, a community 15 kilometres south-east of Alice Springs.

Two years later the Aboriginal Land Rights (NT) Act 1976 was established, which paved the way for the newly-formed council to claim back and manage traditional lands.

Senior First Nations academic Marcia Langton, who spoke at Saturday’s event alongside former CLC director and former WA Senator Pat Dodson, said it was “the first time in Australian history” Aboriginal land rights were genuinely recognised.

“[The Act] still today represents the highest point of recognition of Aboriginal rights in land,” she said.

Ms Langton, during her five years as an anthropologist for the CLC in the 80s, consulted with traditional owners to develop land claim documents and lodge those with the federal court.

“I wanted every land claim to win. I think in my time we lost one, I think I worked on about 20,” she said.

“People’s understanding of their country, their knowledge of their country and their ability to give evidence in compliance with the Land Rights Act criteria for traditional owners was just astonishing … one of the great experiences of my life.

“In the nation’s history, [the land council is] a profoundly important institution.”

The celebrations on Saturday featured traditional dances, bands and singers, with crowds gathering from communities across the NT’s south to warmly support the performers.

A number of council stalwarts were also honoured throughout the day, and two truth-telling sessions were held.

One was a women-only event on the banks of the Todd River remembering the 1990s protests against plans to build a flood mitigation dam, which traditional owners say would have destroyed a sacred women’s site.

Many community members said the highlight of Saturday’s event was seeing young children take part in traditional dances.

“They learning the little kids as well for the women’s dancing, so they can grow up and continue dancing around their kids,” Arrernte traditional owner Phyllis Stevens said.

“The young generation will carry on the dances and stories and songs … keep the country strong and the land,” Annette Williams said.

Next generation to forge the CLC’s future

Mr Williams, who was elected as chair last month, said he would like to see young people step into council leadership roles and help the CLC “expand”.

He also said he’d like to see more women standing for the CLC ahead of the next council elections in April 2025.

“In that time [the CLC was formed] it was all men … it changed dramatically when women come on board,” he said.

“We [now have] about a third women on the CLC board.”

While the event was alcohol-free, organisers said they were disappointed their requests for local takeaway outlets and bottle shops to close on Friday and Saturday went largely unanswered.

Lhere Artepe was the only business to heed the calls, with the Aboriginal Corporation closing its three IGAs on Saturday.

“I commend Lhere Artepe for leading by example and urge others to show some responsibility and follow suit,” Mr Williams said ahead of the event.

An ABC news story.

The Central Land Council (CLC) has launched two new resources to assist traditional landowners to make the most of their native title rights.

The two booklets, How to Claim Native Title, and Native Title and Mining, were launched by the CLC at Ross River, with elected members travelling to the location an hour east of Alice Springs immediately after the council’s 50th anniversary celebrations on Saturday, October 5. The new resources are designed to complement existing booklets and information, and will be translated into Aboriginal languages to help people understand native title mining and claim processes under the Native Title Act (1993).

CLC CEO Les Turner said these resources will help empower traditional land owners.

“Knowledge is power, and these new booklets aim to return power where it belongs – with the native title holders…” Mr Turner said.

“This enables Aboriginal people to have a seat at the table to negotiate agreements when something is happening on their traditional country.”

The meeting at Ross River also marked the last meeting of elected members during this council’s term, with elections set to occur next April. CLC executive leadership will continue to meet every two months, with Mr Turner saying the council is hoping for more diversity in its applicants in 2025.

“Our chair and other members have been encouraging young people and women to join them on the next council,” Mr Turner said.

We mourn the loss of Elliot McAdam AM, former NT local government and housing minister, former Barkly Regional Council member and a man who spoke truth to power no matter who held it.

Mr McAdam was an outspoken and tenacious advocate for his people, especially women and children, and always put their rights and wellbeing first.

Central Land Council executive member and former chair Sammy Wilson recognised these qualities when he and Mr McAdam were youngfellas, mustering together at Everard Park Station in the north of South Australia.

“I grew up with him and he was like family to me. We loved riding horses. I’ve been learning from him. He never gave up for people. He made me think about how to look after the country. When I went up to Tennant Creek I always visited him.”

The Central Land Council members are proud to have fought side by side with Mr McAdam for alcohol restrictions in Tennant Creek in the 1990s, which he led as a senior staff member at the Julalikari Council, for Aboriginal rights and better living conditions.

As a prominent voice of the NO MORE campaign he spoke out passionately against family and domestic violence and as chair of the Barkly Region Alcohol and Drug Abuse Advisory Group he raised awareness of the root causes of alcohol and other drug abuse while working hard to address them.

He richly deserved his appointment as a Member of the Order of Australia for his integrity and many decades of service to his people.

Our hearts go out to Barb Shaw, his daughters, extended family and many friends.

Warlpiri woman Alice Henwood is an expert tracker from Nyirripi.(ABC Alice Springs: Victoria Ellis)

“Nyiya Nyampuju?” What is this?

The call rings out across the red clay and sand.

The voice belongs to Warlpiri woman Alice Henwood from Nyirripi, a small community about 400 kilometres north-west of Alice Springs.

“Nyiya Nyampuju?” she asks again.

The group of people, spread out like the tufts of spinifex across the land, slowly gather around to look at where she is pointing.

They are quiet.

Alice knows the answer to her question, but right now she is teaching.

Finally, someone speaks up.

“Wardilyka,” Bush turkey, he guesses correctly.

The questions continue.

“Ngana-kurlangu?” Whose is it? “Nyarrpara-purda?” Which direction?

A group of people are tested on their tracking knowledge.(ABC Alice Springs: Victoria Ellis)

Over and over she asks the group with each new set of tracks that are found.

There are many of the puluku, cow.

There’s also the ngaya, cat, the puwujuma, fox, the warnapari, dingo and excitingly, the endangered walpajirri, bilby.

Full story here: Warlpiri preserve language, culture through animal tracking program for next generation – ABC News

Jeffrey Curtis has been waiting a long time for a new ranger hub in Tennant Creek, but now it’s come — and he’s looking forward to seeing how it helps young people in the remote Northern Territory town.

The new Muru-warinyi Ankkul Ranger base, built by an Aboriginal-owned construction company, is bigger and airier than the last, with modern amenities.

The ranger group had previously been splitting their operations between two locations, but the upgraded single site replaces what was basically “a very old shed”, according to Mr Curtis.

“I’ve been waiting for a new one for a very, very long time, maybe 10 or 15 years,” he said.

“I’m very happy for this new ranger hub and I hope it can do better for the future for our young ones.”

Rangers as role models

Muru-warinyi Ankkul Rangers was established in 2003 and is one of the oldest Central Land Council ranger groups.

The rangers care for country by monitoring plants, animals and water, but they have also mentored Tennant Creek high school students; up until the work experience program was stopped due to COVID-19.

Ranger Kylie Sambo said she hoped to restart the program.

“It [learning about country] starts early. If they know it when they’re young, it’s easy for them when they are older to get back to their roots,” she said.

“This is just a fun way of trying to work with non-Indigenous people on country.”

Tennant Creek has long been facing problems of youth crime, but Ms Sambo knows first-hand the power of positive role models.

“When I was at school I would go on a lot of trips with Central Land Council and write up essays about what we were doing on country and that would give me credit with school,” she said.

“That helped me a lot with being on the streets and doing all of these things that are happening now.

“I watched them [rangers] as a kid first and then said to myself, ‘I’m gonna be a ranger some day’. And sure enough, I am.”

New hub cooler and closer

The new ranger shed has a large fan, lockers, a tool cage, welding benches and, outside, a pressure cleaner and wash bay, while the house on the property received a new kitchen, bathroom, furnishings, solar panels and air conditioning.

A new conference space and server room will allow the site to be used as a training facility, while space for heavy equipment storage means the site can be a central hub for other ranger teams from Arlparra, Lajamanu, Daguragu, and Ti Tree.

Ms Sambo said having a new truck and tractor stationed at the hub will also be a boon, as central regional rangers previously had to travel to Alice Springs to borrow big equipment.

“[The hub] can make a huge difference with the time the rangers spend on roads to get to places and then come back to do the job, and then get that equipment back to where it came from,” she said.

“That’s been one of the biggest problems.”

Modern way of caring for country

Ms Sambo said the new hub would help her work on country and learn about her culture.

“And I’m being paid to do that, which is very important, because with this society we live in, everything revolves around having funding, having money to do so,” she said.

“The ranger program that’s in place allows us to tackle jobs given to us by traditional owners and that is also deeply important to us, because we are connected to the country.

“This is just a modern way of taking care of country and taking care of family and taking care of the plants and animals.”

Mr Curtis said the rangers made him proud.

“[I’m] very happy with my group. We were established from 2003, but we’re still going,” he said.

“This ranger group has achieved a lot — a lot of training has been done and a lot of land management and conservation … it’s made us a stronger group.”

An ABC news story posted 20 Feb 2024

The old store in Engawala has been given a new lease of life, opening as an arts centre.

With few jobs in the community, Engawala’s many talented artists now have a dedicated space to work and earn an income from arts and crafts sales.

Tourists often drop in on Engawala, 200 kilometres northeast of Alice Springs, because the community is next to the Alcoota fossil fields. Those visitors now have a proper place to view and buy the artists’ work.

“The community are really supportive of the arts centre. Especially the board as well and Joy Turner, the elder for this community,” arts centre manager and Engawala local Janine Tilmouth said.

“We did this project so that there was a chance for people to have work and also to have their own community-owned arts centre, instead of someone else coming in and running it,” she said.

They first talked about turning the old store into an arts centre four years ago.

The community allocated a total of $145,000 to the renovation, which was made up of community lease money and matched funds from the National Indigenous Australians Agency.

Four residents then met with the Central Land Council’s community development team and Tangentyere Constructions to work out the details.

“The workers gave the old store a good clean-out and got electricity, benches and drawers,” resident artist Sharon Tilmouth said.

They boarded up some doors and fixed broken windows to make the building safe.

“We had to wait a while to get the work done, but Tangentyere Constructions did a good job,” Janine Tilmouth said.

“They listened to the community and suggested what would be good, with the sink and putting the drawers in.”

Tangentyere Constructions hired local residents Stewart Schaber and Leanne Dodd for some of the work and finished the job within six weeks.

“I helped pull out the fridges and I was painting the wall and glazing the floor. It’s the first time I’ve done this kind of work,” Ms Dodd said.

“I liked getting to work on time and communicating with the other workers.”

She also helped Tangentyere’s Aboriginal tradies Corey Coull and Adrian Shaw to coat the floor and install the benches and trolleys.

Ms Dodds is a local artist and helped the other artists with the designs painted on the floor.

The locals took over the centre ahead of the official launch in August.

“The arts centre looks good inside now. We’ve already started to work in the arts centre, doing paintings. I’m working at the shop now.”

Volunteers from Community First Development, a national organisation which connects skilled volunteers with Aboriginal communities, Taffy Denmark and Marella Pettinato were a big part of the project.

They helped write a business plan and sourced a $100,000 grant from the Aboriginals Benefit Account to paint the old store and build a shade structure. Now the artists can paint outside in good weather.

The money also paid for an eco-toilet, art equipment, insurances, governance training and project management.

During a year-long construction delay staff took part in intensive administration training.

“I got a lot of training from the volunteer Marella, for admin and bookkeeping and getting work-ready for the auditor. It’s a lot of work and I’ve learnt a lot,” said Janine Tilmouth.

Artists are also getting training from art professionals, and 12 community members have enrolled with the Batchelor College to complete visual arts certificates.

“The ladies have been screen printing,” Sharon Tilmouth said. “There was a workshop and one lady taught us. Lots of ladies have been using the arts centre and they’re happy with it.”

A $400,000 grant from the Indigenous Visual Arts Industry Support program pays for a website, the wages of two local art workers for two years and covers the costs of attending interstate art fairs.

Janine Tilmouth said the centre will build on sales through the art fairs and allow them to explore other markets.

“Maybe we can take our artworks to the cities, spread the word and add more to the website,” she said.

The Engawala art centre shows what can be achieved when Aboriginal people work with a lot of different people and organisations to drive their own development.

The money for this project came from the income the community receives from leases of its land and a three-year trial by the CLC and the NIAA.

The matched funds trial funds groups that use new income from land use agreements for community driven projects, but may not have enough money for the projects they want.

If you would like more information about this work please visit https://www.clc.org.au/strengthening-our-communities/

Ltyentye Apurte (Santa Teresa) has become the first remote Aboriginal community in the Northern Territory to fund its very own outdoor concrete skate park.

Nicky Hayes, Eastern Arrernte man and Spinifex Skateboards founder, has been the driving force behind this project.

A keen skateboarder since the age of 11, he became one of the few Aboriginal skateboarders to compete professionally and the NT’s first Aboriginal qualified skateboard instructor.

His next goal was to bring the benefits of skate boarding to his community, 80 kilometres south east of Alice Springs.

Ltyentye Apurte started out with a single skate ramp in 2017 and upgraded to a wooden double storey skate course in the recreation hall.

It launched the outdoor skate park last September.

“This is my way of giving back to community,” Mr Hayes said.

“Having an indoor park, and then from the indoor park to this outdoor park here right now.”

“An outdoor skate park brings a bit more to the community, but also more to young people and families as well. “

For the past four years he has run weekly skateboarding workshops at the recreation hall and the basketball court with the Atyenhenge Atherre Aboriginal Corporation and the youth program of the MacDonnell Regional Council.

“I wanted the skate park to improve the wellbeing of the kids in Ltyentye Apurte,” Mr Hayes said.

“To ensure they stay active and to have an outdoor skate park where families can hang out and accommodate young people’s needs of having fun within a safe space for skateboards, bikes and scooters.”

The skate park near the store, footy oval and basketball court has become another place where residents socialise and enjoy sport.

Mr Hayes took his idea for the $436,600 outdoor skate park to a community meeting two years ago.

A local working group that plans projects with the Central Land Council agreed to fund some of the project cost from Ltyentye Apurte’s community lease income and income from a pilot project of the CLC and the National Indigenous Australian Agency, on the condition that grant funding make up the balance.

“The working group were happy to be part of something that is unique, to be the first community to have an outdoor skate park,” Mr Hayes said.

The community’s Atyenhenge Atherre Aboriginal Corporation and the CLC’s community development team helped the working group to get the project done.

The CLC sourced the grant from the Aboriginals Benefit Account that made the park possible.

Construction started last August, with designers Eastbywest and builders from Grind Projects working every day to complete the park in five weeks.

The local kids made the park their own by painting parts of it with their designs. A painted Aboriginal flag also features prominently.

The community has plans to put in a shelter and landscaping to soften the area and add shade.

Some of the best skateboarders in the country came for the opening of the park to celebrate this Australian skateboarding history event.

Mr Hayes hopes they will keep coming back.

“Bringing competitions here might be a great thing as well, down the track,” he said.

For now he is just happy that the local kids visit the park every day until dark, spending less time on their screens.

“It has been tremendous to see all the kids in the community having fun and enjoying themselves each day.”

Warlpiri elders and expert trackers are leading a program in northern Australia to teach younger generations how to read Country.

In June 2022, some of the most respected elders of the Warlpiri nation gathered for a workshop in Lajamanu, a remote town in the northern Tanami Desert, south of Kalkarindji. It was one of the largest such gatherings in recent years and, were it not for the flies, it could have been the Roman senate: here were the elders of the nation, gathered to discuss the great issues of the day. One minute they were talking about complex matters of law and ceremony and custom. The next they debated the intricacies of Warlpiri language and stories of the past.

Any resemblance to the ancient Romans was truly ended by the fact of women being at the heart of this gathering; they wore beanies and cast-off clothes. There was much laughter, mobile phones rang often, and arguments erupted over such topics as which species of snake had left behind tracks across the red sand nearby. This was especially significant, for the elders in attendance were also the Warlpiri’s kuyu pungu, or master trackers.

Many, perhaps even most, of those present grew up in the desert or out bush. There, they learnt to read the tracks of the animals: which animal left the tracks, where it was travelling, and how long ago it passed by. The kuyu pungu at the Lajamanu workshop were from a long line of Warlpiri people who grew up learning how to read the country. Over time, they entered into an intimacy with the land that went to every aspect of their lives – kinship, ceremony, survival. The current kuyu pungu, those gathered at Lajamanu, were the last in that long line.

By the time that most of the workshop’s participants had reached adolescence, their desert lives were if not lost then much curtailed. Travelling between missions, cattle stations and cities, they worked as drovers and domestic help, if at all, returning to country whenever they could. Aside from rare exceptions, their children and grandchildren had little opportunity to learn the old ways. Torn between the lure of the cities and the obligations of the past, the young Warlpiri returned to country at weekends, if they were lucky, where they picked up fragments.

This is why the Warlpiri elders gathered in Lajamanu. Part of an ongoing project known as Yitaki Mani (“Reading the Country”), the aim of the workshop was to find a way to bridge that gap between generations, to address the possibility that some knowledge may soon be lost forever, and to find new ways to teach a people who no longer grow up on country. Run by the Central Land Council, the program and the workshop – and other workshops like it across Warlpiri country – faced the most daunting of tasks: to distil thousands of years of lived knowledge into teaching materials and techniques that could work in a classroom.

Witnessing the sessions – which ran under the guidance of Warlpiri elders, pastor Jerry Jangala and Myra Herbert Nungarrayi and others, assisted by linguists and anthropologists – was like watching an encyclopaedia unfold in real time. Flow charts emerged, the frequent use of photos maintained the visual essence of the experience, and field trips – to Emu Rockhole or the track to Tennant Creek – kept things practical. There were times when momentum seemed to unravel. On one of the excursions, a goanna had the misfortune to appear close by. Consequently, much of the day was “lost” as everyone shared a goanna feast around an impromptu fire. But like other seeming distractions – a sudden recitation of a Dreaming story, or an unplanned detour down a side track to honour a cultural obligation – these moments deepened the stories and the ability of these kuyu pungu to tell them.

“We have to make sure we all have all the knowledge, that knowledge of how to read the country. And that knowledge comes in many ways,” says Jangala. “We need this knowledge if we are to get back the old Warlpiri ways.”

The establishment of the Yitaki Mani program reflects changes in Australia regarding First Nations peoples, and builds on those defining points in the process of reconciliation. Recognition of citizenship in 1967, the development of land rights in the 1970s and the outstation movement in the 1980s all represented the move away from the nation’s integrationist impulse.

Yitaki Mani builds on this process, drawing from another nation-shifting development: Indigenous ranger programs. Running for more than 15 years, the establishment of these initiatives has expanded across the country, and there are now around 130 federally funded ranger programs, with additional state-funded groups. Most of them operate on Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs).

So successful have ranger programs become that their funding became a campaign issue during the 2022 federal election. The Morrison government promised to double the funding for Indigenous rangers, to $686 million over eight years. Labor matched this commitment and added $10 million per year to expand the programs.

From a conservation perspective, every now and then work undertaken through the ranger program makes headlines, and is credited with significant successes. Indigenous ranger groups have, for example, been central to the discovery of new night parrot populations across Western Australia.

Stephen van Leeuwen, the Indigenous chair of biodiversity and environmental science at Curtin University in Perth, says ranger programs have enabled conservation activities to operate on a much broader scale than would be possible through scientific programs working alone. “You can’t have an IPA without a ranger program. And you can’t have an IPA ranger program without a healthy country plan. You’ve got a workforce and people who want to be there.”

Van Leeuwen recognises the importance of elder knowledge in the process of engaging the younger rangers. “Yes, you want to empower [First Nations peoples] by giving them meaningful work. But the elders in the communities want to manage the country, and that commitment quickly flows on to the younger people in the community. They want to look after their country … Lots of the threatened species that are still extant are on the Indigenous conservation estate in the deserts and in northern Australia, so there must be something good happening there.”

The ranger program is also driving a wider re-evaluation of traditional forms of knowledge and storytelling. Successes like that of the night parrot “demonstrate the power of proper two-way science”, says Steve Murphy, an ecologist who has worked extensively with traditional owners. “Indigenous people were highly attuned and acutely aware of all aspects of the environment that they were living in over millennia. So the observational-based science that they built up was incredibly detailed. In many cases, people aren’t living 24/7 on country and aren’t needing to get their whole subsistence from these landscapes. It’s pedalled back a little – it’s more a knowledge about place and landscape. But it’s still there, and it’s better than any [geographic information system] and remote-sensing analyst can give us.”

Much has also been lost, Murphy acknowledges. “Historically, a lot of that ecological knowledge would have been held by people, but it’s gone. We have to acknowledge that it has gone from so many places. And that is another very important and often overlooked role of two-way science – rekindling and rebuilding that knowledge.”

It is with this backdrop of loss and renewal that the Yitaki Mani project carries such potential. If it is successful, its organisers hope benefits won’t be restricted to the Warlpiri. The conceptual frameworks and teaching materials will become available to other communities, enabling them to tap into their own deep wells of knowledge.

It is, as ever, a race against time, something of which the elders at the Lajamanu workshop are keenly aware. “Some of the young ones are interested, and want to learn more,” says Jerry Jangala. “But some are losing their culture, their ceremony, everything. It’s not good for our people. It’s not good for Australia. Our country will be lost. That’s why we’re here. To teach them another way to learn. After all, one day I won’t be here with you.”

Article written by Anthony Ham and published in The Monthly.

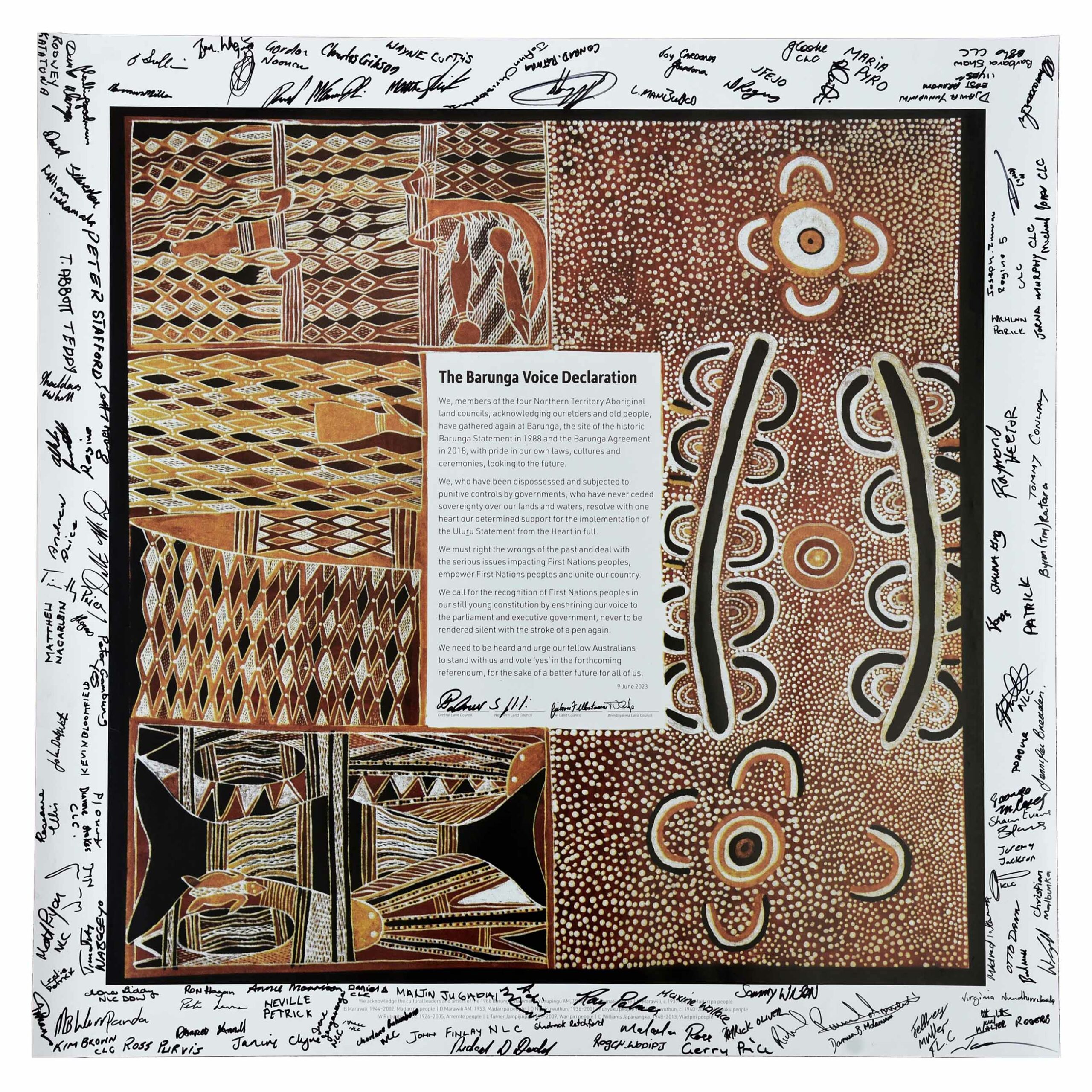

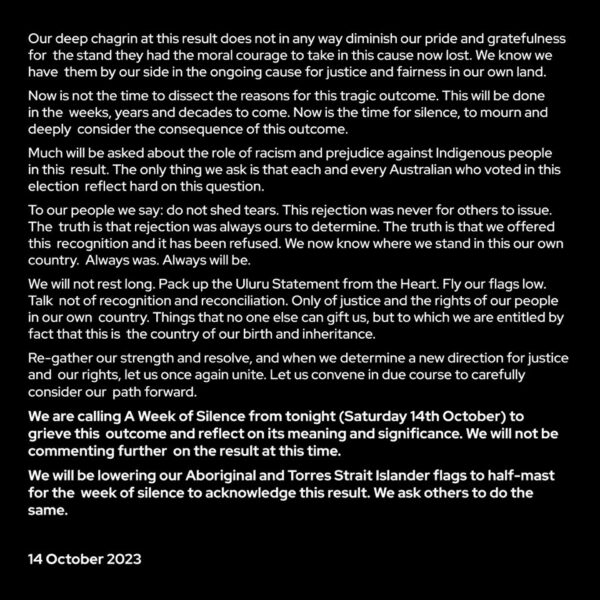

The ignorance expressed about the voice is only surpassed by the lack of knowledge about the rigorous process that led us to it.

I wonder who Senator Jacinta Price is referring to when she talks of “my people”.

She can’t mean the people I work for – 90 democratically elected Aboriginal men and women from the towns, remote communities and hundreds of tiny homelands of the southern half of the Northern Territory. People aged between 20 and 80, who are elected for three-year terms, meet three times a year out bush and who, for the past five years, have consistently expressed their strong support for the constitutionally enshrined voice to parliament the senator opposes.

A voice that allows local representatives to be heard about laws and policies that affect them and offer solutions informed by their unique knowledge and lived experience. What could be more practical? What could be fairer, more modest and unifying?

View the full feature article online here

A federal plan to protect threatened species has neglected almost all of central Australia and will not stop extinctions, wildlife advocates say.

The 10-year Threatened Species Action Plan was released last month, highlighting 20 important natural places and 110 national species of concern to be prioritised for protection.

Central Australia’s only priority area

Through the Northern Territory’s Central Land Council, traditional owners co-manage the MacDonnell Ranges National Park, which is the only priority area in central Australia listed in the federal plan.

Eastern Arrente man and land council chief executive Les Turner said rangers were poorly funded and unable to adequately manage the millions of hectares they were responsible for.

View the full feature article online here.

Ninety years after Pitjantjatjara man Yukun was killed by police and his remains sent to museums in Adelaide, he is finally laid to rest.

On the day Yukun was returned to Uluru, his descendants leapt into the deep, narrow grave to help ease him to rest as their elders looked on, weeping.

The ceremony, at the base of the rock on an unusually cold and rainy morning, helped ease the pain of almost 90 years of unfinished business that began with a Northern Territory police shooting in 1934.

View the full feature article online here.

The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) is an Australian government agency based in Canberra.

The objective of the ANAO is to support accountability and transparency in the Australian Government sector.

The ANAO is currently reviewing the governance of Land Councils in the Northern Territory.

Governance means doing things the proper way in organisations, according to rules, culture and the law.

We would like to hear your views on how the Central Land Council (CLC):

- Manages the operations of the CLC on behalf of Aboriginal people

- Conducts consultation with Aboriginal people

- Helps Aboriginal people and traditional owners manage and look after country

- Reports on the CLC’s performance

- And any other views you may have on how the CLC works

Please provide your responses before 30 September 2022 by:

• sending an email to the ANAO at clc@anao.gov.au or

• calling the ANAO on 0476 249 221 or

• submitting your comments on the ANAO website at www.anao.gov.au/clc

Any information you provide is confidential – it will not be shared with anyone outside of the ANAO.

Once we have finished collecting information, we will write a report that will be presented to the Australian Parliament in March 2023. It may contain some recommendations to help improve the governance of the CLC.

Alekarenge students are getting job-ready without having to leave their community, thanks to an innovative horticulture work experience trial.

The Alekarenge work experience pilot program is a partnership between Alekarenge Horticulture Pty Ltd and Centrefarm.

It helps middle and senior school students in the community south of Tennant Creek to gain valuable industry experience.

The students learn to grow crops such as garlic, pumpkins, cabbages, zucchini and watermelons alongside adult workers on the Aboriginal-owned farm near the community and also study horticulture at school.

Economic stimulus funding from the Aboriginals Benefit Account, administered by the Central Land Council, has allowed the project to expand its farm.

The project is using the $1,619,000 grant to buy equipment, build infrastructure and pay wages.

It has seen the first 10 trainees from the community graduate with a Certificate 1 in Agrifood Operations last year.

It has also sold fresh produce to Aboriginal-owned supermarkets in Tennant Creek, Alice Springs and Alekarenge’s Mirnirri Store.

The students also sold the store zucchini chocolate muffins and zucchini fritters they made.

“The funding will go a long way towards providing training and employment opportunities,” Centrefarm’s Joe Clarke said.

The work experience trial aims to offer fulltime work for six to 10 students, or a higher number of parttime placements, before it concludes in 2024.

The CLC’s economic stimulus funding has assisted 14 Aboriginal businesses and organisations with a combined total of more than $17 million in approved grants in 2021.

The money is helping to set up new ranger groups out bush, fund an Aboriginal economic development forum in Alice Springs, support another horticulture business near Ti Tree and kick-start or expand several social enterprises.

One of them has created some competition for Central Australia’s only funeral service.

Desert Funerals, a joint venture between Ngurratjuta and Centrecorp, aims to bring down the high costs of farewelling loved ones.

“Desert Funerals brings new competition to the market whilst committing to culturally appropriate and affordable funerals,” Centrecorp chief executive, Randle Walker, said.

The plan for a not-for-profit, culturally sensitive funeral service for remote communities and town was hatched in late 2018 and the service moved into an office near the Alice Springs cemetery last October.

Almost $400,000 in economic stimulus funding has helped the social enterprise get started, with the business holding its first funeral service in February.

Mr Walker said the funds were “instrumental in assisting Desert Funerals to become a credible alternative funeral provider through funding for hearses, building alterations and funeral equipment”.

Tennant Creek is not missing out on stimulus funding either.

When the Julalikari Council’s Jajjikari Café re-opened at the Nyinkka Nyunyu Art and Culture Centre in early 2020, after it had been closed for five years, the CLC’s stimulus funding allowed it to branch out into street food.

The Jajjikari Café smoko truck is literally a vehicle to train two Aboriginal workers in hospitality and customer service.

“The smoko truck drives around to businesses and the community living areas, serving home made fresh treats,” Julalikari’s Jacqulin Pereira said.

The $190,000 grant also paid for equipment for outdoor film nights and music events, a stage and a jumping castle for the school holidays.

The project goes some way towards meeting the demand for Aboriginal tourism experiences and quality catering services in the town.

The CLC’s economic stimulus project was made possible by an injection of $36.7 million from the Aboriginals Benefit Account in November 2020. For more information email aba.stimulus@clc.org.au, call (08) 8951 0667 or, or go to https://www.clc.org.au/aba-economic-stimulus-package/

Enid Gallagher leaned forward over the spinifex and clutched her chest in fear. Suddenly, she wasn’t just showing the three young men from Nyirrpi how to track brush-tailed mulgara, she had become the frightened animal.

The animal in question is a small, threatened marsupial Yapa call jajina.

“Jajina wake at night when the lightning strikes,” she said, and pointed to the burrow beneath the spinifex.

Her teenage students learn the difference between fresh and old kuna (poo) left by the small marsupial, and read the tiny footprints around their burrows.

They listened carefully to their kuyu pungu (master tracker), and filled out their work sheets.

Reading and learning the country (yitaki mani) is part of a workshop by eight senior Yapa knowledge holders, educators, Central Land Council rangers from Yuendumu, Nyirrpi and Willowra and other staff.

The week-long workshop at the Newhaven Wildlife Sanctuary, 363 kilometres northwest of Alice Springs, included Nyirrpi high school students so they could road-test new learning materials developed by the Yitaki Mani project working group.

The workshop is part of a new CLC project that aims to find out how senior Yapa knowledge holders pass on a lifetime of learning and caring for country to Yapa who grew up in settlements.

Unlike young people today, kuyu pungu and Warlpiri Ranger Alice Henwood was born out bush, west of Nyirrpi, and learned to live off the land. “I’m one of the last bush ladies,” Ms Henwood said proudly.

Now in her sixties, she learned to track as soon as she could walk and follow her parents and aunties on the hunt.

Ms Henwood’s journey took many years, but she feels a sense of urgency to teach her young colleagues.

“I am worried that when I pass away that knowledge will just disappear. That’s why we have to pass the knowledge to the young rangers now, as well as the young people, so they can pass on to their kids,” she said.

“I am worried that when I pass away that knowledge will just disappear. That’s why we have to pass the knowledge to the young rangers now, as well as the young people, so they can pass on to their kids,” she said.

Warlpiri Ranger Alice Henwood, one of the last people to grow up living off the land.

Yapa and the CLC want to fast-track that learning process so that young rangers have access to yitaki maningjaku – everything you need to know to track.

The project working group developed teaching and learning materials that young people can relate to, but that still foreground Yapa knowledge systems.

Kardiya (non-Aboriginal people) typically trap animals to identify what species live in an area, but this only works if something falls into the trap.

A skilled kuyu pungu, however, can tell you the size, diet, territory and hunting patterns, as well as the speed of travel, age and sex of all the animals, reptiles and insects that left tracks around the trap overnight.

“We teach whitefellas, and we also learn from them too,” said Ms Henwood’s daughter and fellow Warlpiri Ranger Christine Michaels.

“Like with the tablets CLC showed us how to store information about endangered animals.”

Yapa knowledge is not just about identifying the animal, it’s also about the purda nyanyi (sensory awareness) of the expert tracker, which is traditionally stored in their head.

Thanks to funding from the 10 Deserts Project, the Yitaki Mani team is developing tools and resources to maintain and promote this knowledge for generations to come.

“I’m getting a little bit sick now, so I really need to pass my knowledge to the younger rangers and the kids.

I’ve been working for a very long time,” Christine Michaels said. “Today the kids from Nyirrpi were really excited to go tracking for jajina and warrarna (great desert skink) and count the burrows.

I was really happy with that.“If young people want to become a ranger they have to work to know their country, spend time with elders on country, and not go into town drinking,” she said.

The fate of the NT’s largest ever groundwater extraction licence at Singleton Station hangs in the balance, as distressed traditional owners challenge the science behind the decision and the effectiveness of water laws.

By Samantha Jonscher, ABC Alice Springs.

View the full feature article online here.

Robert Jampijinpa Robertson’s vision for a Yuendumu-owned and operated transport and vehicle recovery service is one step closer to reality.

Xtra Mile, the social enterprise he started, began running chartered bus services in June.

The milestone followed two years of planning with the Central Land Council’s community development team and volunteers of Community First Development, a com-munity development and research organisation.

“Members were coming and asking if we can take them to Lajamanu, Papunya and all those places, and that’s when I started to think we need to start a bus service or something for our people to get to places they want to go,” Mr Robertson said.

Yuendumu residents have long endured expensive and infrequent transport services, and people traveling to Alice Springs are often stranded for days, missing work and school.

Mr Robertson successfully pitched the social and employment benefits of his bright idea to the community committee of the Granites Mine Affected Area Aboriginal Corporation in May 2019.

Later that year, the committee allocated almost $98,000 to set up a social enterprise and buy two Toyota coaster buses, and almost $27,000 for two remote transport services consultants.

In 2020 it contributed just over $164,000 towards the company’s first year of operations, enabling it to run a charter bus service and establish trust with its customers.

Xtra Mile aims to offer a regular and reliable bus service to the whole community, with return trips between Yuendumu and Alice Springs costing around $160.

Mr Robertson named the company in memory of the travel his family used to undertake by foot.

“In the logo is a little boy being carried by his father,” he said.

“My father used to carry me on his shoulder when I used to get tired, so he had extra load on. He would carry a spear and me on top of all the stuff he was carrying. Extra mile.”

Mr Robertson sourced an additional $250,000 from the Aboriginals Benefit Account, allowing Xtra Mile to employ a social enterprise worker for two years.

Xtra Mile set up shop in an office rented from the Yuendumu Women’s Centre.

The centre also provided secure parking for the buses, and the Wanta Aboriginal Corporation is helping with human resources, governance and financial systems.

Xtra Mile aims to generate enough income to cover a third of its operating costs in its first year.

It is also training and employing locals.

Four Yapa drivers completed commercial passenger vehicle training in Yuendumu, passed their theory exam, medical assessment and got a police certificate.

Two more drivers will undertake the driver knowledge test and a medical assessment in Alice Springs before attending the second Drive Safe NT training in Yuendumu in September.

The company hopes four more drivers will upgrade to a light rigid vehicle license class.

Mr Robertson is proud of what he and the community have achieved so far.

“I think the whole thing is great training and jobs for our mob in the desert, and to strengthen your own business and help people understand what things are possible,” he said.

The traditional owners of the Yeperenye Nature Park near Alice Springs have launched a walking and cycling trail between Anthwerrke (Emily Gap) and Atherrke (Jessie Gap) that they financed, built and gifted to the public.

After six years of planning and design and more than six months of construction, around one hundred people gathered at Anthwerrke on July 27 to celebrate the official opening of the trail with a smoking ceremony and a kangaroo tail lunch.

The traditional owners used $365,000 of the rent income they get for the jointly managed national park to fund the trail – the largest sum any Central Australian Aboriginal group has ever invested in public infrastructure.

“It makes me really proud that we did that — putting our money from the government back to the trail here,” traditional owner Lynette Ellis said.

“We did this trail for all of us here, for our young kids now and for our future generations.”

At a time when the industry needs it most, this new public trail will open up another section of the East MacDonald ranges to tourism and local employment.

“Not many tourists come to Jesse Gap, they are always going to the West Macs, so we thought it would be something good to do to attract them out this way,” Ms Ellis said.

“There might be some sort of tour around here with tour guides. We will be doing more projects.”

More than 30 Aboriginal workers built the 7.2 kilometre trail by hand, trained in unique sustainable trial construction by local company Tricky Tracks.

“It has been good learning new skills and being able to work hard and share this sacred place with everyone,” Mr Grant Wallace, a traditional owner and worker on the track said.

“I’m looking forward to using these skills for future trail work around here.”

“This on-the-job, one-on-one training will allow these workers to build and maintain trails across the region,” CLC CEO Lesley Turner said.

Cultural supervisors were on site during the construction to ensure important sites were respected and protected.

The trail which follows the contours of the East MacDonnell Ranges and will feature interpretive signage at the trail heads.

The trail features rest stops and is wheelchair accessible in two sections to ensure visitors of all abilities can benefit from increased access to the East Macs.

Mr Turner told the crowd that the trail shows what can be achieved when traditional owners and local stakeholders work together to realise their ambitions to the benefit of all.

“I want to thank the owners of the Yeperenye Nature Park for their generosity, inclusivity and forward-thinking,” he said.

“You have left a legacy that’s making us all very proud. Of course you were not only thinking of us visitors.

You had your families and young people foremost in your minds and you spread the work around.”

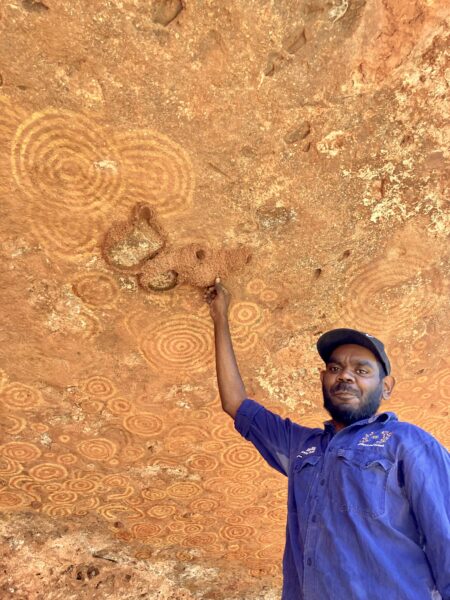

The Ltyentye Apurte Rangers have removed swallow nests from the paintings of their most significant rock art site – with a little help from their friends from Kaltukatjara (Docker River).

Traditional owner Damien Ryder led the convoy of two ranger groups on a trip to Utyetye, a large open cave at the bottom of a cliff on the Santa Theresa Aboriginal Land Trust, to watch them restore the paintings covering the cave roof to their former glory.

He stood at the edge of a cliff that turns into a waterfall after heavy rains, and creates a curtain across the cave opening while topping up the bright green water below.

“The old people used to camp here,” Mr Ryder said, gesturing down into the narrow valley beyond the cave that the rangers have recently cleared of reeds.

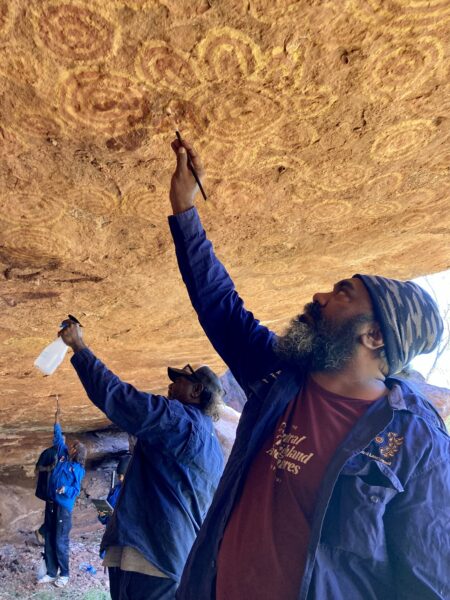

Bernard Bell, from Kaltukatjara, clambered down the steep rock face with a cardboard box under his arm, ready to show his colleagues what he learnt at Walka, a cave full of rock art his group is protecting back home.

“I’m teaching them how to look after these paintings and clean off the mud nests,” he said as he inspected the mesmerising design of concentric circles in yellow and orange ochre that covers almost the entire roof of the cave.

Then he pulled a wooden stick and a small hammer out of the box and started to carefully chip away at one of the dozens of mud nests stuck to the ochre.

When only a narrow rim of mud was left he pulled out a spray bottle filled with a clear fluid.

“We spray it with methylated spirits to make the mud soft,” he explained.

The moisture revealed even more paintings underneath the wet mud as he gently swept away the last of it with a soft paint brush.

“We use the brush to clean off the rest of the mud, spray it again, brush again, until it looks nice and clean. It works well. It never takes off the rock painting.”

“It’s been here for a long time and that’s why we need to look after it.”

Farron Gorey, from Ltyentye Apurte, got the hang of it right away.

“It’s a bit different from other ranger work,” he said.

His colleague Anton McMillan already had some practice, having learned the technique during a visit with the Kaltukatjara group.

“My first time was at Docker, where I was doing some training for this kind of work,” he said.

“Nobody has come out here before to clean out the swallow nests to look after all the paintings. It’s part of the history for this country, that’s why it’s important.

“I reckon the traditional owners will be happy with it.”

Mr Gorey agreed.

“I feel good that we can continue to do this, so the old people can see it,” he said.

“I want to bring them here to show them what we have learned. When they see this they are going to feel happy.”

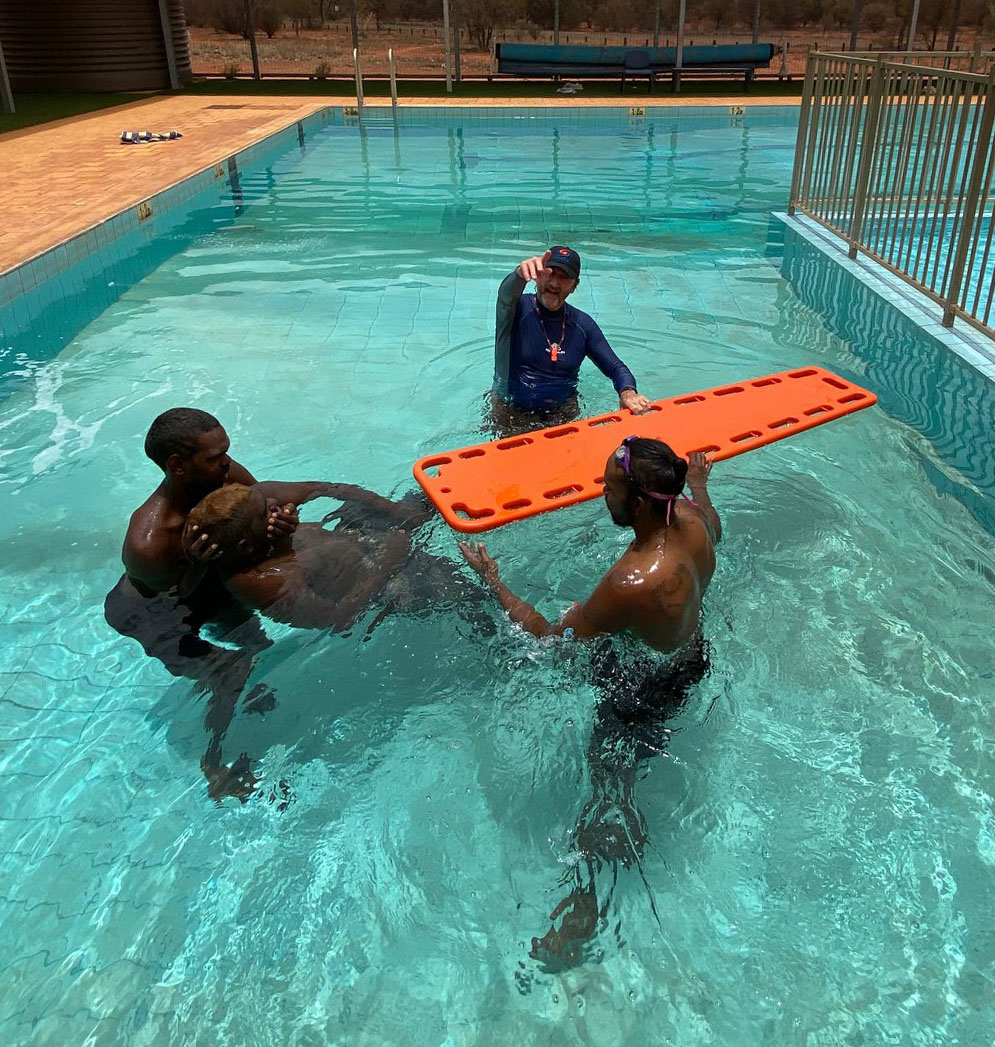

Mutitjulu has its very first home grown life guards to patrol the community’s popular swimming pool.

Five young men undertook lifeguard training in January, and two have qualified as lifeguards.

Clem Taylor and David Cooley completed the course, and Daniel Breaden, Terrence Rice and Christopher Dixon are expected to qualify later in the year.

Mr Taylor and Mr Cooley are now working at the pool as fully qualified lifeguards, alongside the trainees. “I like helping look after the kids and learning about the pool,” Mr Taylor said.

While locals have worked as casual pool attendants and helped to run events, the lifeguards are a first.The lifeguards know how to help someone after a heart attack, provide emergency care and rescue people from the water.

They had to show they could swim at least 200 metres, tow people, and get them out of the water safely. They learnt how to make the whole pool area safe, how to prevent problems and accidents and how to report them. They also worked on their communication skills through role plays and practised how to prevent and deal with problems and conflict.

The training course, like the pool, is funded by the community’s rent income from the Uluru—Kata Tjuta National Park. Using their new qualifications and work experience, the young men can also apply for work at the Yulara pool.

The new lifeguards have brought the community one step closer to its goal of managing the pool all by itself.

Native title holders and community residents have asked the Central Land Council to fight a water licence decision on Singleton Station if it is approved unchanged. Fortune Agribusiness has applied to pump up more than 40 billion litres of water annually, for 30 years, to grow fruit and vegetables on the pastoral lease south of Tennant Creek.

If the government grants the controversial application, the company would be able to take, free of charge, every 12 months more than four times as much drinking water as Alice Springs uses in a year.

It would be the largest private water allocation in the Territory’s history and would irrigate one of Australia’s biggest horticulture projects.

Native title holder Roger Tommy said the company is asking for too much. “We don’t want them to take all that water, we may have no water left for our communities,” he said. “They can have two bores, but no more than that. If you got a big mob of bore, you’re using up too much water.”

Senior knowledge holder Donald Thompson, who grew up in the region and worked around Singleton, said the proposal may be too risky.

“We’re worried that the country will dry out, and with no water there’ll be losses of all the animals and wildlife,” he said. “That’s why we’re talking really strongly to the government about this proposal.”

Traditional owners, residents, businesses and scientists are concerned that too little is known about how the company’s plan would affect native plants, animals, sacred sites and community drinking water in years to come.

A big meeting of native title holders and affected residents in Tennant Creek in February said independent water scientists must be allowed to check the licence, its conditions, the company’s ‘adaptive management framework’ and the way the government plans to manage the licence – a process known as ‘peer review’.

If that review shows it is too unsustainable and risky the meeting wants the CLC to fight the decision.

“We’re worried about the water levels dropping and we want to consult with people who know how much water there really is,” Mr Thompson said. “We got to know how much [water] is in the ground because that’s an important resource that could be lost. That knowledge should inform the decision. The government should find it out first, before they start making big project decisions.”

Elder Michael Jones implored the meeting to think about future generations. “Twenty to 40 years down the track – will the traditional owners have enough water?” he asked.

“Our kids got to survive, and the animals. They need to do more testing about how long that water is going to last.”

Independent water scientist Dr Ryan Vogwill has reviewed the Northern Territory Government’s water planning on which the Fortune Agribusiness application is based. He warned the meeting that the planning is “high risk” because it is based on too little information.

Dr Vogwill said the planning ignores the most culturally and ecologically important places, such as wetlands, springs and soaks, an oversight he called a “major gap”.

“There are more gaps than there are areas with a high level of understanding”, he said.

Water expert Dr Dylan Irvine, from Charles Darwin University, has also criticised the lack of data. “There’s modelling from Fortune Agribusiness. The issue with that model is it’s based on scant data, and we don’t know what the impact on salinity is going to be in the shallow aquifer region,” he said.

Dr Vogwill found there were “high levels of uncertainty” about the modelling and about how plants and animals would be affected. He wrote “the Murray-Darling is a good example of what happens” when lots of water is taken out of a system before we know what will happen down the track.

Tim Bond, a senior government water planner, told the meeting “we know enough about what’s likely to happen. We have put together a model based on our best estimate”. He said more research and monitoring would happen after a licence decision.

The government plans to practice ‘adaptive management’, saying it could cut back the water allocation if there turns out to be less water than it thinks.

The company would “get a little bit of water and if all goes well they get a bit more”, Mr Bond said.

“Adaptive management means that you are reacting to a problem when it has already happened,” executive member Michael Liddle countered. “There’s too many unknowns to take this risk.”

“You can’t give us a straight answer and we’re not happy with the whole process,” he said.

The process “is fraught with risk that may result in undesirable impacts on the environment or big reductions in allocations that may have serious project feasibility or negative economic outcomes,” according to Dr Vogwill.

No wonder small Aboriginal-owned horticulture pilot projects around Singleton are feeling threatened.

Centrefarm applied on behalf of the Iliyarne Aboriginal Land Trust for a 1,000 megalitre water licence for a horticultural operation south of Wycliffe Well. The company also trains young people at its horticulture training centre near Alekarenge, with promising results.

It fears these projects could become unviable if all of the Singleton application is granted.

“Teenagers who have been disengaged from school have been attending to learn about horticulture and are growing, harvesting and selling their own veggies to the community,” Centrefarm’s Joe Clarke said.

“The project is giving these young people opportunities to work on country, but its future depends on nearby Aboriginal-owned projects having sustainable access to groundwater that could be threatened by the massive Singleton application.

“It would be a real shame if the allocation put our training centre and Iliyarne’s plans at risk. These young people are the future and they must be the priority,” he said.

Native title holder Heather Anderson struggled with the idea that horticulture companies would get the water for free from the NT Government. “Water is not for free, water belongs to the land. It should stay there,” she told the Guardian news site.

The ‘free’ water is worth a lot of money, and that attracts companies to the Territory. “If this water was being extracted from the Murray Darling Basin, we’d be talking in the order of $20 million a year for that water use,” Dr Irvine told the ABC.

Mr Liddle does not believe the government will ask the company to pull out fruit trees and irrigation lines later on, if its “guesswork” turns out to be wrong.

“No future government will have the political will to cut back the water allocations of companies that have already invested millions of dollars,” he said.

Nobody may find out if there are problems because the government trusts the company to do the monitoring.

Maureen O’Keefe grew up around Singleton, where her parents worked and met.

“We’re not worrying about money, we’re worrying about life,” she told the meeting.

“We have climate change and we don’t have rainfall every year. I’ve been crying for this country. All the springs will be dried out. Then we got no name for them anymore. All the cultural sites will suffer and we will have no stories to tell for our kids,” she said.

CLC chief executive Joe Martin-Jard is also concerned that the government’s planning does not take into account global heating. “We’re mining a very precious, finite fossil resource that is likely to dwindle even further due to climate change and more frequent droughts,” he said.

“It would be extraordinary if it made such a far reaching decision based on assumptions and guesswork.”

Environment groups said the application should be rejected because even small errors in the government’s modelling could cause irreversible problems.

“There is no guarantee of how or when those water resources and the communities and ecosystems that rely on them would recover,” Kirsty Howey, from Environment NT, told the Guardian.

“And we’re not sure that they would, in fact, ever recover. That means that extreme caution should be exercised.”

CLC executive member Michael Liddle agreed. “Our water is too precious to rush this or get it wrong.”

Harry Jakamarra Nelson had planned to sit down with Land Rights News for more than a year to talk about his long and distinguished life as one of the nation’s land rights pioneers.

Sadly, an accident, followed by long months in hospital in Adelaide and Alice Springs, forced Jakamarra to postpone the interview several times and, in the end, the man who gave so generously of his time and knowledge all his life simply ran out of time.

He died surrounded by his loved ones in Yuendumu at the start of February. His family has given the Central Land Council permission to publish this tribute to its executive member and long-term delegate.

“Jakamarra was a land rights champion of the first order and commanded enormous respect,” CLC chief executive Joe Martin-Jard said. “He often described himself as ‘a CLC man through and through’.”

That sentiment expressed by CLC chief executive Joe Martin-Jard aptly sums up the life and career of Jakamarra Nelson.

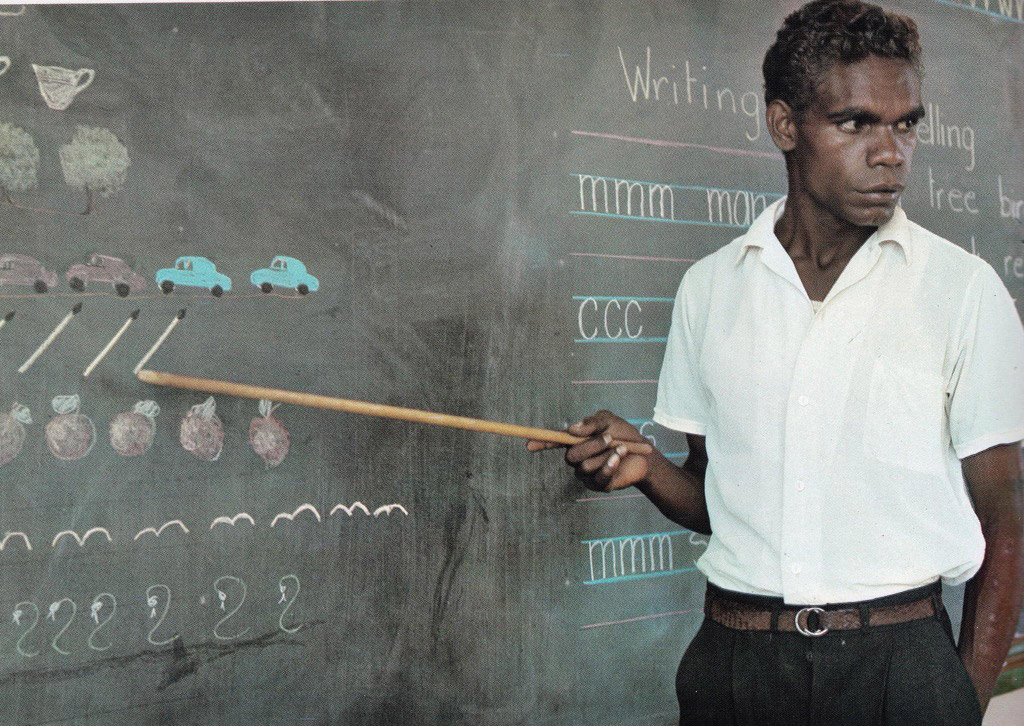

Born on Mount Doreen Station, Mr Nelson was six years old when his family was moved to Yuendumu, a welfare ration depot, around 1946. He was the fifth of nine siblings and his father had four wives.

Even though he only attended the community’s school until grade five, he benefited from many extra lessons by Baptist missionary Tom Fleming.

“I was lucky,” Jakamarra recalled in the CLC’s oral history collection Every Hill Got A Story. “The whitefella missionary used to teach me after hours … to give me extra education. That’s where I managed to pick up my command of English.” He considered himself blessed to have received a two-way education, with regular breaks from settlement life. “You’d go to church every Sunday, practice our culture every night if possible,” he said.

On frequent trips to his family’s country “we had explained to us how far, how long it would take from A to B to get there – walking that is, cross-country with no map recorded, except in your mind. I think I could still do that – but I can’t walk!” After a mechanic’s apprenticeship Mr Nelson attended teachers college in Darwin and returned to the Yuendumu school as one of the first Aboriginal teachers in Central Australia.

“There were two of us, one at Alekarenge and myself,” he said. After five years of teaching Jakamarra decided the adults needed his help more, and he joined the Department of Aboriginal Affairs to support the outstation movement as an assistant community advisor.

He was a champion of Aboriginal-led economic and community development, serving on the advisory committee of the Aboriginal Benefit Account and as a director of Yuendumu’s Yapa-Kurlangu Ngurrara Aboriginal Corporation and always had the back of the CLC’s community development team.

As a director of the Granites Mine Affected Areas Aboriginal Corporation he helped to fund projects with mining compensation income that support Yuendumu’s most vulnerable, particularly the elderly.

A lifelong advocate of truth-telling, one of Mr Nelson’s last public appearances was as master of ceremonies for the 90th anniversary Coniston Massacre commemoration at Yurkurru in 2018. He was a nephew of Bullfrog, who died when Jakamarra was a young fella.

At the commemoration, he talked about the disastrous consequences of his uncle’s killing of the white dingo trapper Fred Brooks in 1928. “Hundreds of Aboriginal people got shot by the punitive party led by Constable George Murray. They just went beserk,” he explained. “I’m not angry,” he told the ABC. “The truth needs to be told, that’s all. It’s time that we move on and live in harmony.”

To help with this healing, he and other Yapa leaders believe we need a public holiday to mark the massacres. As for Yurkurru, one of the massacre sites: “I would like to see this turned into a national park.”

His call remains unfinished business, but one who would remember it is Labor’s Warren Snowdon who attended the commemoration with his “close friend for over 35 years”. “We have lost a great friend and a leader of passion and conviction,” the member for Lingiari said in February.

“A strong voice that demanded to be heard, a person of great intellect and knowledge.”Another admirer, anti-domestic violence activist Charlie King is working on establishing an award in Mr Nelson’s name.

He told the NT News the award would recognise outstanding work in the fight against domestic and family violence and should become one of the annual NAIDOC awards. Mr King recalled that Jakamarra inspired the name for “No More”, the awareness campaign that works with sporting clubs to reduce family violence.

When the activist spoke with a group of Yuendumu men in 2006 about the shocking rates of domestic violence in the Territory, Jakamarra responded by waving his finger, saying “No more. No more.”

“How powerful is that?” Mr King said. “We will remember him for being a giant.” Jakamarra will also be remembered as a peace maker, who along with other senior men and women travelling between Alice Springs and Yuendumu, helped to prevent an explosion of grief and violence in Yuendumu following last year’s police killing of Kumanjayi Walker.

“It was through their leadership, calling for calm, calling for peace, calling for justice” that worse was averted, even though Jakamarra did not achieve his aim of moving the trial to Yuendumu, Mr Martin-Jard told the ABC.

“He wanted to see his people to see justice being done.” Mr Nelson worked as a Warlpiri interpreter during the early land council meetings and represented his community of Yuendumu on the council since 1988.

But more than 40 years later, following the most recent CLC elections in 2019, he told the many new young delegates why he was not yet ready to retire. “We are still very strong and still battling with the government and others who are damaging our country. I’m talking about the mining companies. That’s why I joined the land council,” he told them.

Mr Martin-Jard said that leadership will be missed. “He was a thorough gentleman who walked with ease in two worlds. We will all miss his wisdom and his humour,” he said.

Jakamarra leaves some big shoes to fill, and not just at the CLC.

“Mr Nelson was a fighter to the end,” Mr Snowdon said. “I met with him recently and he hoped those following in his footsteps would continue to protect knowledge, country and culture.”

Our thoughts are with Mr Nelson’s wife Lynette, his children and families.

Source: Land Rights News – March 2021

Students in Mutitjulu, Watarrka and Utju are soaking up traditional knowledge at school, thanks to a partnership between Tangentyere Council Land and Learning and the traditional owners of the Uluru – Kata Tjuta National Park.

Each school worked with local elders to plan bush excursions and what they wanted to teach on the trips.

Utju studied bush medicine plants, with students learning to prepare rubbing medicine from the witjinti plants they had collected out bush, and drinking and rubbing medicines from ilintji.

The elders’ knowledge, along with the students’ drawings and photos of the excursions, were then used to create teaching resources in Pitjantjatjara and English.

At Utju, they made two language books, Irmangka – Irmangka Palyantja, about making rubbing medicine from eremophilas, and Punti, Muur-muurpa, Witjinti munu Ilintji, Utjuku miritjina irititja kuwaritja, about how to use senna, bloodwood, corkwood and native lemongrass.

“It was a good story and the pictures too. Palya, it’s colourful and a good story,” assistant teacher Rachel Tjukintja said.

Teacher-linguist Leanne Goldsworthy agreed. “The book is beautiful and informative. It’s a great resource to have and a record of knowledge so it won’t be lost,” she said.

Anangu elders, the CLC’s Tjakura Rangers and the national park rangers took Mutitjulu students to Kata Tjuta to harvest urtjanpa (spearwood). They cut mulga wood for wana (digging sticks) and clap sticks from the surrounding woodlands and collected kiti (resin) from the mulga leaves.

They also made kulata (spears) and dug for maku (witchetty grubs). Back at the school, the elders showed the students how to finish their punu (wooden tools) and prepare kiti. They helped the students to record on worksheets what they had learnt. “We make kulata, wanaand music sticks. It was fun, I liked it,” student Sarah Lee Swan said. “The ladies teach us how to make them from the tree with different tools. I want to go camping next time.” Student Nazeeria Roesch agreed. “Yeah, fun. I make stick. I look for maku. Yes, let’s go again,” she said.

Maruku Arts provided the tools for this pununguru palyantja (making tools from trees) trip. With some planned trips cancelled due to COVID-19, Watarrka students illustrated Yaaltji ngiyarilu tjilka mantjinu (How the thorny devil got his spikes), a story told by Brian Clyne and translated by Julie Clyne.