Native Title

The Central Land Council became a native title representative body under the Native Title Act (1993) in 1994.

We prepare native title applications, respond to development proposals with the potential to impact on native title rights and interests (‘future acts’), negotiate indigenous land use agreements (ILUAs) and support many corporations representing native title holders known as prescribed bodies corporate (PBCs).

Information Booklets

In 2018, we published the Native Title Story booklet, an easy-English introduction to native title and PBCs for native title holders.

In 2021, the government changed some of the rules in the Native Title Act so we made a new Native Title Story booklet.

We also produced Native Title on Cattle Country, an easy-English information booklet about native title on pastoral lease land.

In 2024, we added two booklets to help people understand their native title rights and opportunities.

How to Claim Native Title is about the claims process. Native Title and Mining is about agreements with mining companies.

PBC Camps

In 2019, we held the first forum for native title holders in Central Australia, also known as the PBC camp, at Ross River, near Mparntwe (Alice Springs). Eighty native title holders from across our region attended.

We responded to their feedback and held a second PBC camp in June 2021. We prepared a report for native title holders and committed to hosting the forum every two years. Read about the most recent camp in June 2023.

PBCmob

The mobile phone app PBCmob offers our constituents native title resources in Arrernte, Alyawarr, Kaytetye, Pitjantjatjara, Warlpiri, Warumungu and easy English. The free app provides access to publicly available documents related to their PBCs and builds their understanding of native title and associated rights. We plan to add content in more local languages over time.

PBCmob is user-friendly and accessible on both iOS and Android devices. It works even without an active internet connection.

Native title determinations

The Federal Court legally recognises the existence of native title. Most native title determinations in Central Australia are by agreement between all parties without the need for a trial, in other words, by consent.

In our region the court has made the following determinations:

2024

Native title determination at Huckitta Station to be the strongest of its kind

The traditional owners of Huckitta Station will receive the strongest form of native title under the Native Title Act – exclusive possession.

On 22 May, the Amapete, Apwetyerlaneme, Atnweale, and Warrtharre native title holders of Huckitta Station will celebrate a native title consent determination.

Justice John Halley of the Federal Court will deliver the decision in the Plenty riverbed next to the Huckitta homestead, roughly 270 kilometres northeast of Alice Springs.

The native title holders purchased the Huckitta pastoral lease in 2010 with the assistance of the Aboriginals Benefit Account, and the Huckitta Aboriginal Corporation took over as the leaseholder.

Research on the native title claim began in 2011, and a native title determination application was filed in the Federal Court on 23 October 2020.

This makes it one of the longest-running claims in the CLC region.

Senior native title holder Kevin Bloomfield is glad the wait is finally over.

“After all our stories were written down and sacred sites, we was waiting a long time,”

“When that judge comes out and hands over that paper, I’m going to feel happy because we were waiting too long,” Kevin Bloomfield said.

The research for the claim included ‘exclusive possession’ native title, which also incorporates the right to take, access and use resources for any purpose–including commercial rights.

These rights will cover almost all the claim area of nearly 1700 square kilometres.

Central Land Council CEO Les Turner said native title rights differ from land rights.

“The determination allows native title holders to hunt, gather, conduct cultural activities and ceremonies in the area, as well as utilise resources from the land for an economic benefit.”

“What’s special about this determination is that the traditional owners hold the pastoral lease, which allows the native title holders to control access onto the station, but unlike under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act, they have no veto right over mining.”

Native title holders and court staff will celebrate the event by cutting a cake to mark the occasion.

The Huckitta Aboriginal Corporation will hold the native title rights and interests for the determination area.

2023

Native title determination to help protect sacred salt lake sites from mining

Karinga Lakes native title holders are about to receive recognition of their right to protect their sacred sites from more damage from mining and exploration.

The Anangu [ARR – na – ngu] native title holders of the Karinga Lakes area, approximately 250 kilometres southwest of Alice Springs, will celebrate a native title consent determination on the morning of 5 April.

Judge Mordecai Bromberg of the Federal Court will hand down a determination covering more than 10,000 square kilometres of pastoral lease land including Warltunta [WAL – tun – ta], or Erldunda Station, Maratjura [MAH– rah – joo – rah], or Lyndavale Station, and Tjulu [JOO – loo], or Curtin Springs Station.

The native title holders asked the Central Land Council in 2016 to lodge the Karinga Lakes claim because they want to protect the culturally and environmentally sensitive salt lakes from potash mining by Verdant Minerals, who hold exploration licences overlapping the lakes.

Some of the songlines that traverse and create the lake system are part of a major men’s tjukurpa [JOO –koor – pah], or dreaming.

Senior native title holder David Wongaway said the lakes are sacred.

“The whole lake is important to old people. It is sacred to men and women.”

Anangu have cared for the area since time immemorial.

“I was born on the land ancestors slept on,” native title holder Cyril McKenzie, said.

“Aboriginal people, Anangu, look after the land. Salt lake is older than tjukurpa. Elders tell us this is where tjukurpa is. Follow tjukurpa.

Anangu and Lyndavale pastoralists brought damage to the lakes following substantial drilling and trench excavation to the attention of the CLC in 2013.

Following extensive anthropological and legal research, the land council helped the native title holders to file the claim in 2020.

The native title holders would like Verdant Minerals to respect their rights as nguraritja [NGOO – rah – rit – jah], or traditional owners, and leave the lakes alone.

“We want no more digging holes on the land,” Mr Wongaway said. ”

Salt lake is damaged over the years with mining. Now we can say protect the land. It is part of the tjukurpa. It is connected,” Mr McKenzie added.

The native title holders are disappointed that the National Native Title Tribunal has to date failed to protect the lakes.

2021

Return to country: Jinka and Jervois stations native title determination brings people home

The traditional owners of the Jinka and Jervois cattle stations have celebrated the recognition of their native title rights.

Justice Charlesworth handed down a non-exclusive native title consent determination in May, during a Federal Court sitting in Bonya, a community living area excised from Jervois Station near the Northern Territory/Queensland border.

“It is a proud day today. Happy the court is here to recognise our native title, but also a bit sad because thinking about all those people who should be here, but not anymore,” Marlene Doolan, a member of the Thipatherre estate group, said.

“I think they must be here in spirit, and always will be here, watching over us.”

The determination area covers almost 5,000 square kilometres, including the two pastoral leases, a stock reserve and a disused stock route that cuts the stations in half.

The stock route crosses many cultural and historical places of significance to Aboriginal people, including sacred hills which form part of the Two Eaglehawks Dreaming.

The native title holders belong to nine land holding groups from the Ankerente; Arntinarre, Arraperre, Artwele, Atnwarle, Ilparle, Immarkwe, Ltye and Thipatherre estate groups.

The determination allows them to hunt, gather, teach and to conduct cultural activities and ceremonies in the area.

Native title holder Alan Dempsey was pleased about the determination.

“This is my grandfather’s country, Mr Dempsey said

“He worked on the station, and his father, and his father, and his father before him.

“The part we got is Jinka Springs. In the old days it didn’t matter about station boundaries or anything like that. We had our own water. We had Rain Dreaming there,” he said.

The area became a cattle station in 1909 and early mining exploration began in the 1920s.

Both shaped the lives and family structures of the north-eastern Arrernte people as it did their country.

Many families left their traditional homelands due to violent incursions from settlers. Others left to find work further east across the Queensland border.

Christine Doolan was born in Boulia, a four hour drive over the border. She remembers the stories about this country from her grandparents.

“My grandfather walked over that way with my grandmother, they took my mum and two uncles.

“It took them a whole year to get there. It was one of those bull carts, and one of the uncles nearly drowned in Marshall Creek, and his brother saved him. He was about four years old then,” she recalled.

“I’m very pleased, but it’s also a bit sad, too, this determination. It took a long time, and it’s what the old people were fighting for.”

From the 1920s onwards, the area was home to copper, silver and lead mines where many of the men worked. They travelled between mines and stations, visiting family.

Prospector Tom Hanlon discovered copper in the area in 1929 while droving horses down the Arthur River. He recognised the tell-tale green stain of copper on the Jervois Range, which is known as atetherre (Eastern Arrernte for place where parrots get their green) and the site of the Budgerigar Dreaming.

The Central Land Council lodged the native title claim in 2018 in response to renewed mining interest on the stations.

KGL Resources acquired the Jervois Base Metal Project, a proposed open-cut copper and silver mine in the Jervois Range, in 2011. It negotiated an indigenous land use agreement with the native title holders in 2016, two years before the CLC lodged the native title claim.

The government approved the proposed $200 million mine in January.

Francine McCarthy, the CLC’s manager of native title, said the determination gives the native title holders the right to negotiate exploration and mining agreements.

“But unlike on Aboriginal land, they have no veto right,” she said.

David Blue, a native title holder from Bonya, said that the determination gives traditional owners a seat at the table with pastoralists and mining companies.

“Something’s better than nothing. Now we have a bit of rights, and a bit of a voice,” he said.

The native title holders will exercise their rights through their prescribed body corporate, the Ingkekure Aboriginal Corporation, which takes its name from the Eastern Arrernte word for eagle claw.

2020

Limbunya native title holders celebrate recognition

A feeling of celebration was in the air as everyone present for the Limbunya native title determination jostled for space under the marquee for a group shot.

Native title holders posed with representatives of the Federal Court for photos marking the long awaited determination over the childhood home of land rights leader Vincent Lingiari.

Justice Richard White handed down the determination at the Karungkarni Arts and Culture Centre in Kalkaringi, witnessed by the Nawurlala, Parayi-Kakaru, Tjutamalin and Central Limbunya land holding groups.

The more than 5,000 square kilometre determination area, northwest of Kalkaringi, belonged to Lord Vestey’s cattle empire and was run as part of Waterloo Station until the 1980s. As on all Vestey stations, conditions were extraordinarily difficult for Aboriginal workers and their families.

Despite being paid in rations and shifted around from station to station and across state and territory borders, they maintained a very rich cultural life against the odds. They kept their songlines alive as they travelled around, and as relatively distinct cultures intermingled, the Vestey stations became a crossroads of many song traditions.

It was not uncommon for station workers from the vast northwest region to walk hundreds of kilometres to Limbunya during the wet season to attend ceremonies.

After Mr Lingiari led striking Aboriginal workers off Wave Hill Station in 1966, families working on Limbunya and other Vestey-owned stations joined the strike.

Pauline Ryan’s husband Banjo Ryan Jangala, a former Limbunya stockman, was recognised as a native title holder. “I was from Wave Hill Station, he was from Limbunya Station. We met in Kalkaringi many years ago and now we are both native title holders in a week,” Ms Ryan said, referring to the Wave Hill determination Justice White handed down two days earlier.

Many of those present were born on one of the stations, and walked off in 1966. The celebration brought together people who had not returned to their country since the strike with members of the Stolen Generations – descendants of those who were taken away from Limbunya as children.

Josie Crawshaw and her sister had travelled from Darwin to attend the determination in memory of their grandmother who was born on the station.

When her grandmother was four, she and her three siblings were separated and removed from their family at Limbunya.

“They were taken away by a policeman, all four kids were on one horse, with the policeman sitting behind. They rode all the way to Darwin.”

“It means so much to us to be here,” Ms Crawshaw said. Many of the native title holders live in Kalkaringi and Daguragu and continue to visit the station for cultural and ceremonial reasons.

“We’ll take our children to learn the dances on country,” John Leemans, who had travelled with his wife from Katherine, said. “Before he passed, I promised my uncle, he asked me to see this through. It was very important to him.”

The native title holders will exercise their rights through their prescribed body corporate, the Malapa Aboriginal Corporation. They nominated directors on the morning of the determination and started their first meeting by identifying inappropriate or derogatory settler place names, such as ‘Nigger Creek’.

The corporation will ask traditional owners to choose better local language names to submit to the Northern Territory Place Names Committee.

Source: Land Rights News (October 2020)

Wave Hill’s long wait for native title rights ends

More than half a century after the late Vincent Lingiari led the strike on Wave Hill Station, the native title rights of the strikers’ families have been formally recognised by the Federal Court.

Justice Richard White handed down the historic determination at Jinbarak, the site of the old homestead, and acknowledged the historic significance of Wave Hill as the site of the 1966 walk off that sparked the land rights movement.

“I think all of us here today would recognise that this is a particularly special determination of native title,” he said. “We’re not returning land, what we’re doing is recognising that the Jamangku, Japuwuny, Parlakuna-Parkinykarni and Yilyilyimawu land-holding groups have had interests in this land at least from the time of European settlement, probably for millennia.”

The non-exclusive consent determination means that the native title holders and Wave Hill pastoralist share access to almost 5,500 square kilometres of land. Francine McCarthy, the CLC’s manager of native title, said the determination recognises their rights to hunt, gather and teach on the land and waters and to conduct cultural activities and ceremonies.

“It gives them the right to negotiate exploration and mining agreements, but unlike on Aboriginal land, they have no veto right,” she said.

To those who took part in the walk-off, recognition of their enduring connection to country is about telling the truth about our shared history and how it shaped Aboriginal lives.

“I was born on Wave Hill Station. It means everything to me and my family,” said native title holder Pauline Ryan, who at age 10 was put to work at the homestead cleaning, ironing and washing bedsheets by hand. Her mother taught her how things were done on the station. Pauline never went to school.

“I was about 15 years old in the walk off in 1966, I remember that day. My stepfather, mother and grandpa were there too.“My uncle and grandpa and grandma passed away here. We bring our young kids here to talk about their memory.”

Many people who took part in the walk off made the journey to Jinbarak to witness the latest chapter in their quest for self-determination and to honour those who had passed away. Strikers Paddy Doolak and Jimmy Wave Hill welcomed everyone to Gurindji country.

Timmy Vincent, Mr Lingiari’s only surviving son, acknowledged his father and “those old people who aren’t here today.”

The last time Milton Splinter, who lives in Alice Springs, set foot on his country was 1966. “I was six years old when my people walked off the station.

I was born right over there. As a kid I used to play along these creeks, so this place is very important to me. Today is the first time I’ve been back. ”Wave Hill Station was established in 1883 by drover Nathaniel Buchanan, and in 1913 became part of Lord Vesty’s British cattle empire. By 1966, generations of stockmen and house servants had endured years of drought, deprivation and exploitation.

Instead of wages, they were doled out tea, sugar and tobacco, even after pastoralists had to pay them a wage set at half of the wage of non-Aboriginal workers.

Vestey’s refusal to pay triggered the strike. Pauline Ryan said life at Dagaragu, where the families settled, was better. “We had what we needed there. We could go hunting and grow vegetables and camp together.”

The families wanted to use a section of land to start their own cattle business on their own country. Their petition for a grant of a pastoral lease of 1,300 square kilometres around Dagaragu stated: “We feel that morally the land is ours and should be returned to us.”

They did not win the right to run cattle until 1975, when Prime Minister Gough Whitlam poured a handful of earth into Vincent Lingiari’s palm. Native title holder Matthew Algy said native title matters to his family today .

“It’s important to the legacy of the old people who worked here. I’m carrying on in my father’s footsteps, he was a stockman and I am a stockman. I was born on New Wave Hill Station, I’ve worked here [Wave Hill Station] like my father did.”

“It’s important to my family, but I’m also sad for the people who didn’t live to see this,” he said.

Source: Land Rights News (October 2020)

2019

Native title recognised on sugar bag country

“It means a lot to us, for our land, our country.” Jerry Kelly spoke for many of the traditional owners of Tennant Creek Station as he greeted the recognition of his native title rights over the pastoral property.

“We can keep the country going, make sure the sacred sites are looked after. We can make sure that no damage happens to the trees, sacred sites and waterholes if the country gets burned off,” Mr Kelly said.

Justice Natalie Charlesworth handed down a non-exclusive native title consent determination over an area of approximately 3,650 square kilometres to seven land holding groups, during a Federal Court sitting near Lirripi, on the cattle station some 36 kilometres south of Tennant Creek, in early July.

The seven land holding groups with traditional attachment to the claim area are Kankawarla, Kanturrpa, Kurtinja, Patta, Pirttangu, Purrurtu and Warupunju groups. “Native title gives us a say over what is happening on our country and protect our sacred sites and dreamings.

If mining or gas companies want to come onto our country, they have to sit down with us and negotiate,” native title holder Jerry Kelly said. “The determination recognises the rights of the native title holders to hunt and gather on the land and waters and to conduct cultural activities and ceremonies,” Francine McCarthy, the CLC’s manager of native title, said.

“It gives them the right to negotiate exploration and mining agreements, but unlike on Aboriginal land, they have no veto right.” Ms McCarthy is also one of the native title holders of Tennant Creek Station. Michael Jones, from the Patta group, said: “What is important to me is that I still can hunt there. And also practice ceremonies, and bring kids out. That’s very important to me.”

“We can go onto country to teach our younger generations about sacred sites and dreamings, and work with the station owner to protect our waterholes with the help of the Tennant Creek rangers,” native title holder and ranger Gladys Brown said.

The CLC lodged the native title application in October 2017, following mining and other development interests within Tennant Creek pastoral lease, which will continue to operate as a cattle station.

The lease area is home to many cultural and historical places of significance to Aboriginal people.

“Their elders and ancestors were born, lived and worked on Tennant Creek Station since the early 1900s,” Francine McCarthy said. “Our grandfather is buried here.

Before government used to put names for old people, they put his name as Chicken Jack Brown and that’s funny, you know,” Beryl Brown, from the Kanturrpa group, said. “Our families are all buried on the land, we know everything about this land, our father taught us when we were kids that this is sugar bag country.”

Like Phillip Creek Station to the north, native title holders were unsuccessful in purchasing the station in the early 2000s when it was placed on the market. Ms McCarthy was pleased the station owner joined the ceremony. “The native title holders of Tennant Creek station have built up a good relationship with the pastoralists, Ken Ford and his wife Leigh,” she said.

“They also lease neighbouring Aboriginal land so they can extend their pastoral operations and also give Aboriginal people an opportunity to be employed and start teaching the younger generations about cattle station life.”

Justice Charlesworth touched many present with her speech.

“For the western mind, it takes some effort to appreciate what it was like here, in this place, before colonisation. Now is the time to make that effort. Now is the time to reflect.”

She invited the audience to hold a minute of silence to honour the ancestors, stating, “Your ancestors are the land.”

Source: Land Rights News (October 2019)

Wurre custodians celebrate title over ancient ceremony ground

Native title holders from the Imarnte land holding group have paid tribute to their elders during the long awaited determination of native title over the men’s ceremony ground known as Rainbow Valley.

“I am feeling very proud about it because my dad and the oldfellas, they all did a lot of work on this. We have waited so long. It is a very important day for us,” Peter Kenny said.

The families gathered at the Rainbow Valley ranger station on May 7 to witness Justice Reeves hand down a non-exclusive consent determination over the 25 square kilometre conservation reserve.

The tourism icon an hour’s drive south of Alice Springs contains important sacred sites and is of great cultural significance.

“Rainbow Valley has always been our country, handed down from grandfather to grandfather,” Eric Braedon said. “It was a big ceremony place for all Imarnte people from all different areas of Imarnte country.

All came in to do ceremony until the white man came and moved us to Maryvale Station.”

The determination has given the custodians a greater sense of control. “I think it is very important that they decided to give us this native title because before, we were not sure whether we were allowed to come here or not. Now we know we can. It gives us more ownership,” Mary Kenny-LeRossignol, from nearby Oak Valley outstation, said.

The custodians have looked after Wurre in partnership with the NT Parks and Wildlife Service since 2005.

Together, they manage the reserve for visitors and protect its cultural and natural values by controlling weeds and fires, for example, and building tracks. “NT Parks and Wildlife and traditional owners will be working together to look after country, and keep this place safe and clean.

We don’t want cars to drive around,” Eric Kenny said. When the Central Land Council negotiated the joint management arrangement with the Northern Territory, the government agreed to consent to a native title claim over the area, but it did not agree to the lodgement of the claim until June 2018.

Mr Kenny said the determination is long overdue. “We have waited for something like this to happen for a long time,” he said.

The CLC’s manager of native title, Francine McCarthy, said the determination recognises the custodians’ unbreakable links to the land. “It means that the native title holders can use the area in accordance with their traditional laws and customs,” she said.

“It recognises that their cultural connection to Wurre dates back to time immemorial, and acknowledges how much the area means to them,” Ms McCarthy added.

Peter Kenny said the decision does not mean traditional owners wanted to drive tourists away.

“We have done a lot of work on this place, we are part of the decision making and we hope that more tourists come in,” he added.

Native title holder and tourism entrepreneur Ricky Orr has been telling visitors about the history of his country since 2008. “The area is a very important meeting place for visiting in the good times when food and water are plentiful and, most significantly, as an ancient men’s ceremonial ground,” Mr Orr said.

The native title holders will exercise their rights through their prescribed body corporate, the Wura Aboriginal Corporation.

Source: Land Rights News (October 2019)

2018

Native title a win in long battle for Henbury

“We been fighting for a long time for Henbury Station,” former Central Land Council chair Bruce Breaden said.

Now well in his 80s, Mr Breaden has been “pushing really hard all the time to get country back” for much of his life. “Not only for my family, but for all Aboriginal people,” he added.

Traditional owners of the cattle property they have long wanted to own under Australian law can now at least call themselves native title holders.

As Justice John Reeves handed down the native title consent determination for more than 5,000 square kilometres of land to six land holding groups at Three Mile waterhole, Mr Breaden took a pragmatic approach.

“We know native title is not strong like land rights, but it gives us a chance to have a say.

We have sacred sites all over Henbury. Native title research was a chance to look around country and show the younger ones,” he said.

The native title holders can now legally visit and protect their sites, hunt, fish, hold ceremonies and try to make agreements about tourism, mining and exploration proposals.

However, they can’t say ‘no’ to non-pastoral development of the station where their elders and ancestors were born, lived and worked since the late 1800s.

There is a cemetery where many loved ones are buried and within the determination area are several outstations on Aboriginal land that are connected by an old stock route.

Some of the old people still speak Pertame, an endangered language they are working to revive, while some speak Western Arrernte and Matuntara Luritja.

The traditional owners have fought unsuccessfully for more than 40 years for the return of their country.

In 2011, after an Australian government assisted purchase transferred the lease to RM Williams Agricultural Holdings for carbon farming, they thought they were close.

The CLC helped them negotiate with the company for a staged return of the land and to source funding for an Aboriginal ranger group to manage it.

When RM Williams went belly-up in June 2013, the traditional owners and the Indigenous Land Corporation tried to buy Henbury Station.

Their plans were dealt a bitter blow though when Henbury was sold to Ashley and Neville Anderson, Ted and Sheri Fogarty and David Rohan, a consortium of established Central Australian pastoral interests. “The ILC was helping, but we didn’t have enough money,” Mr Breaden said.

For now, Henbury will continue to operate as a cattle station, but old ringers never say die.

“We will push it again next time,” Mr Breaden says. “Working on country is good for Aboriginal people.”

Barry Abbott agreed. “I would be pleased to see a ranger group here, but it has to be our people, people from the land. They know how to look after country,” he said.

Robert Coombs reckoned that if Henbury returned to Aboriginal hands the rangers should look after “the waterholes and all the sacred sites”.

“I would apply for it. As long as it is a fulltime job.”

Source: Land Rights News (August 2018)

Anmatyerr mob celebrate native title over all of Pine Hill

Arden’s Soak Bore on Pine Hill Station was the scene of celebrations in May.

Families from five land-holding groups gathered to hear Federal Court judge John Reeves hand down a native title determination over the western side of the property.

The consent determination over more than 1,500 square kilometres west of the Stuart Highway complemented an earlier determination over the eastern side of Pine Hill in 2009.

It means that all of the station, where many native title holders grew up and worked, is now under native title.“I worked for a long time on Pine Hill,” Leslie Stafford Pwerrerl said. “I branded bullocks and broke horses.”

Peter Cole Peltharr said old people told them “the right stories”. “Old Bruce Campbell, he was a cook who told us stories about country and I now pass on those stories to young people,” Mr Cole said.

The native title holders hunt, visit rock holes and practice ceremony on the station, often in the company of the Central Land Council’s Anmatyerr Rangers in Ti Tree.“We feel good when we go to country,” Amy Campbell Peltharr said.

“When the CLC rangers come to help us we go to places we didn’t go to for a long time”. “I teach young people about important places and to do ceremony the right way,” Mr Stafford explained.“I sometimes go to Pine Hill and take young girls to show them how to get bush tucker and medicine,” Daisy Campbell Peltharr added.

“I like to camp out at Pine Hill and look for bean tree seeds with my younger sister.”

Francine McCarthy, the CLC’s native title manager, said the determination recognises these rights under Australian law, as well as the right to negotiate agreements about mining and exploration.

Some of the native title holders want to return to Anyungyunba outstation, across the river from the Pine Hill homestead and hope the native title decision will speed that process up.

“My family have been living there for many years, it would be great to live on my own country,” Dean Pepperill said. “I would like to come and live on the outstation.

I feel grateful for the native title consent determination.“And to try and get it going again, to have more activity and program going again, I have been taking kids there for school holidays – going on country, they love that.”

Source: Land Rights News (August 2018)

Native title holders seek mining and exploration benefits

Traditional owners of cattle stations in the south of the Northern Territory have celebrated native title consent determinations amid negotiations with mining companies. At special sittings of the Federal Court near Titjikala and at Aputula (Finke), Justice Natalie Charlesworth handed down consent determinations over Maryvale, Andado and New Crown stations.

The Maryvale determination took place on the banks of the Hugh River on May 23, followed by a non-exclusive native title consent determination over Andado and New Crown stations, an area of almost 20,000 square kilometres, at Aputula (Finke) the next morning.

The Maryvale area covers more than 3,200 square kilometres and includes an 18 kilometre-wide salt deposit, while further south there are plans for coal exploration.At both ceremonies the native title holders remembered their families who lived on the stations from the 1890s until the 1970s, working as station hands and domestic servants for little more than rations.“It’s bittersweet.

I’m very proud because of the hard work that our old people have put in,” Maryvale native title holder Helen Kantawara said.“Most of them are gone, but we have a few of them here, so we’re celebrating with them here today.“We’ve got lots of stories and song lines, even dances.

We’ve been taught since we were little.“It’s now our turn to make sure that our children here take it on and the knowledge stays strong,” Ms Kantawara said.Eric Breaden said his father and brother have missed out on seeing the determination.“My father worked as a cattle man, a drover and he was born on Maryvale, and my brother,” he said.“I’m the only one left to see this good thing happen. It means a lot to me what’s happening today.”

The native title holders from the Imarnte, Titjikala and Idracowra land-holding groups and the Andado, Pmere Ulperre, New Crown and Therreyererte family groups are happy that their right to hunt and gather on the stations, protect their sacred sites and conduct cultural activities and ceremonies has finally been recognised in Australian law.

“This determination also gives them right to negotiate about exploration and mining activities on their land, but no right of veto,” Francine McCarthy, the Central Land Council’s manager of native title, said.

The Maryvale families are negotiating an Indigenous land use agreement (ILUA) about a salt mine and hazardous waste storage facility with mining company Tellus.“It is exciting if it comes about,” Merilyn Kenny said about the salt mine near Titjikala. “There’s going to be jobs and opportunities for education of our children and young people. I don’t know about the waste dump. I’m worried that they might put something toxic in there, for our water.”

Mr Breaden hopes the mine will create local jobs and seal the road to Alice Springs, but he is equally nervous.“This salt mine happened so quickly and suddenly. We didn’t have any time to talk about it among the family.

Some of the old people still don’t know what’s happening,” Mr Breaden said.“As we were told, the waste dump, they’re going to top it up with salt. We don’t really know what’s going on there in the background. We’re scared of what is going to happen.”Mary LeRossignol met with the company three times, but still wants more information.“I do worry a lot. We don’t really know.

The only time we see them is at a meeting and you can’t really ask that many questions.”

The Southern and Eastern Arrernte native title holders at the determination ceremony in Aputula are trying to negotiate an ILUA with Tri Star, a company that won an exploration permit and

licenses to look for coal and coal seam gas.“Both New Crown and Andado are subject to minerals authorities held by Tri Star,” Ms McCarthy said. The CLC lodged the native title claim in 2013 in response to the company’s oil and gas exploration activities in the region, as well as proposed minerals exploration.Three years later, just before it lost the 2016 Northern Territory election, the Giles government announced it would grant Tri Star mineral authorities for coal exploration. The plan was designed to help the company cut its exploration costs, improve its security of tenure and avoid negotiations with the native title holders.

The CLC lost an appeal against this in the National Native Title Tribunal.The Gunner government granted the minerals authorities late last year, allowing the company to start exploration without an agreement with the native title holders.

The CLC’s efforts to negotiate with the company and its work on the native title claim did not go unnoticed. Artist and native title holder Marlene Doolan, who has lived at Aputula most of her life, presented Ms McCarthy with a ‘thank you’ painting depicting connection to country, dreamings and bush foods.

“I learnt my knowledge from the old ladies who passed it down to me,” Ms Doolan said.“My job is to teach the younger generations today.”

Source: Land Rights News (August 2018)

Native title holders seek mining and exploration benefits

Traditional owners of cattle stations in the south of the Northern Territory have celebrated native title consent determinations amid negotiations with mining companies. At special sittings of the Federal Court near Titjikala and at Aputula (Finke), Justice Natalie Charlesworth handed down consent determinations over Maryvale, Andado and New Crown stations.

The Maryvale determination took place on the banks of the Hugh River on May 23, followed by a non-exclusive native title consent determination over Andado and New Crown stations, an area of almost 20,000 square kilometres, at Aputula (Finke) the next morning.

The Maryvale area covers more than 3,200 square kilometres and includes an 18 kilometre-wide salt deposit, while further south there are plans for coal exploration.At both ceremonies the native title holders remembered their families who lived on the stations from the 1890s until the 1970s, working as station hands and domestic servants for little more than rations.“It’s bittersweet.

I’m very proud because of the hard work that our old people have put in,” Maryvale native title holder Helen Kantawara said.“Most of them are gone, but we have a few of them here, so we’re celebrating with them here today.“We’ve got lots of stories and song lines, even dances.

We’ve been taught since we were little.“It’s now our turn to make sure that our children here take it on and the knowledge stays strong,” Ms Kantawara said.Eric Breaden said his father and brother have missed out on seeing the determination.“My father worked as a cattle man, a drover and he was born on Maryvale, and my brother,” he said.“I’m the only one left to see this good thing happen. It means a lot to me what’s happening today.”

The native title holders from the Imarnte, Titjikala and Idracowra land-holding groups and the Andado, Pmere Ulperre, New Crown and Therreyererte family groups are happy that their right to hunt and gather on the stations, protect their sacred sites and conduct cultural activities and ceremonies has finally been recognised in Australian law.

“This determination also gives them right to negotiate about exploration and mining activities on their land, but no right of veto,” Francine McCarthy, the Central Land Council’s manager of native title, said.

The Maryvale families are negotiating an Indigenous land use agreement (ILUA) about a salt mine and hazardous waste storage facility with mining company Tellus.“It is exciting if it comes about,” Merilyn Kenny said about the salt mine near Titjikala. “There’s going to be jobs and opportunities for education of our children and young people. I don’t know about the waste dump. I’m worried that they might put something toxic in there, for our water.”

Mr Breaden hopes the mine will create local jobs and seal the road to Alice Springs, but he is equally nervous.“This salt mine happened so quickly and suddenly. We didn’t have any time to talk about it among the family.

Some of the old people still don’t know what’s happening,” Mr Breaden said.“As we were told, the waste dump, they’re going to top it up with salt. We don’t really know what’s going on there in the background. We’re scared of what is going to happen.”Mary LeRossignol met with the company three times, but still wants more information.“I do worry a lot. We don’t really know.

The only time we see them is at a meeting and you can’t really ask that many questions.”

The Southern and Eastern Arrernte native title holders at the determination ceremony in Aputula are trying to negotiate an ILUA with Tri Star, a company that won an exploration permit and

licenses to look for coal and coal seam gas.“Both New Crown and Andado are subject to minerals authorities held by Tri Star,” Ms McCarthy said. The CLC lodged the native title claim in 2013 in response to the company’s oil and gas exploration activities in the region, as well as proposed minerals exploration.Three years later, just before it lost the 2016 Northern Territory election, the Giles government announced it would grant Tri Star mineral authorities for coal exploration. The plan was designed to help the company cut its exploration costs, improve its security of tenure and avoid negotiations with the native title holders.

The CLC lost an appeal against this in the National Native Title Tribunal.The Gunner government granted the minerals authorities late last year, allowing the company to start exploration without an agreement with the native title holders.

The CLC’s efforts to negotiate with the company and its work on the native title claim did not go unnoticed. Artist and native title holder Marlene Doolan, who has lived at Aputula most of her life, presented Ms McCarthy with a ‘thank you’ painting depicting connection to country, dreamings and bush foods.

“I learnt my knowledge from the old ladies who passed it down to me,” Ms Doolan said.“My job is to teach the younger generations today.”

Source: Land Rights News (August 2018)

2017

Mabo anniversary: big year for native title

A big year for native title is set to get even bigger.

As Aboriginal people around the country celebrate the 25th anniversary of the High Court’s Mabo decision, which debunked the ‘terra nullius’ lie and kickstarted the Native Title Act, the Central Land Council marked some milestones of its own.

By the time the Mabo anniversary rolled around in June, the CLC had already celebrated its fourth native title consent determination for 2017. Another one is scheduled to take place at Philip Creek on August 3.

In May, Yangkunytjatjara and Matutjara speakers celebrated the first-ever native title determination in the Territory’s south.

At a special sitting of the Federal Court at Victory Downs, Justice Reeves handed down a consent determination over an area of approximately 12,500 square kilometres at the border with South Australia.

The claim area is the second-largest area in the CLC region to have native tilte recognised and includes Victory Downs, Mt Cavenagh, Mulga Park and Umbeara stations.

Native title holders are associated with significant places such as Ananta, Kalka, Watju, Wapirrka and Warnkula, and travelled from far and wide to be there.

CLC chair Francis Kelly, who joined them for the celebrations, shared the joy of the successful claimants. “I am very happy for the families,” Mr Kelly said. “They now have the right to negotiate about exploration, mining and tourism activities on their land.”

In early April, native title holders celebrated native title consent determinations over two pastoral stations and an area including a mineral lease north of Alice Springs at three special sittings of the Federal Court.

Justice Griffiths handed down two non-exclusive native title consent determinations on Aileron Station and one at the Harts Range Racecourse over the whole of Mt Riddock Station, an area of approximately 2,700 square kilometres.

The determinations of native title over the Aileron Station Perpetual Pastoral Lease and the area including the mineral lease known as Nolan Bore took place at Pretty Camp Dam.

They relate to an area of approximately 4,210 square kilometres.

The Aileron native title holders are of the Alhankerr, Atwel/Alkwepetye, Ilkewarn, Kwaty, Mpweringke, Ntyerlkem/Urapentye and Tywerl land holding groups.

Nolan Bore native title holders belong to the Kwaty and Tywerl land holding groups, while the Mt Riddock native title holders belong to the Atwele, IIrrelerre, Ulpmerre and Wartharre land holding groups.

Mr Kelly said all the determinations recognise native title rights, such as the rights to hunt and gather on the land and waters and to conduct cultural activities and ceremonies.

These rights will co-exist with those of the pastoral lessees, who will continue to run the properties as cattle stations.

Source: Land Rights News (August 2017)

Phillip Creek native title sparks memories

The native title determination over Phillip Creek Station has triggered many memories for Warumungu and Warlmanpa families.

“Some of us worked or grew up on Phillip Creek Station or our families told stories of what life was like working and living on the station in the early days,” Norman Frank, one of the native title holders, explained.

“As a young man, my father worked there, doing station work and looking after country,” he added.

In August, Justice Debra Mortimer handed down a consent determination over an area of approximately 3,800 square kilometres during a special sitting of the Federal Court on the cattle station 55 kilometres north of Tennant Creek.

The nine landholding groups with traditional attachment to the claim area, the Kankawarla, Jajjinyarra, Patta, Pirrtangu, Purrurtu, Wapurru, Yurtuminyi, Kanturrpa and Linga groups had travelled from across the Territory to the ceremony at Purrumpuru Waterhole, one of a number of significant waterholes in the claim area.

One of them was the manager of the Central Land Council’s native title unit, Francine McCarthy.

“The determination recognises our rights to hunt and gather on the land and waters and to conduct cultural activities and ceremonies,” said Ms McCarthy.

“It gives us the right to negotiate about exploration, mining and tourism activities on our land while the lessee will continue to operate the lease as a cattle station,” she said.

A good relationship with the pastoral lessee has enabled the native title holders to continue to visit their country and look after it.

Between 1995 and 1998, the CLC negotiated approval for three community living areas on the station for native title holders and their families.

These excisions are not part of the native title determination area.When Phillip Creek Station was placed on the market, in the early 2000s, the native title holders were unsuccessful in their attempts at purchasing it.

Source: Land Rights News (October 2017)

Mabo anniversary: big year for native title

A big year for native title is set to get even bigger.

As Aboriginal people around the country celebrate the 25th anniversary of the High Court’s Mabo decision, which debunked the ‘terra nullius’ lie and kickstarted the Native Title Act, the Central Land Council marked some milestones of its own.

By the time the Mabo anniversary rolled around in June, the CLC had already celebrated its fourth native title consent determination for 2017. Another one is scheduled to take place at Philip Creek on August 3.

In May, Yangkunytjatjara and Matutjara speakers celebrated the first-ever native title determination in the Territory’s south.

At a special sitting of the Federal Court at Victory Downs, Justice Reeves handed down a consent determination over an area of approximately 12,500 square kilometres at the border with South Australia.

The claim area is the second-largest area in the CLC region to have native tilte recognised and includes Victory Downs, Mt Cavenagh, Mulga Park and Umbeara stations.

Native title holders are associated with significant places such as Ananta, Kalka, Watju, Wapirrka and Warnkula, and travelled from far and wide to be there.

CLC chair Francis Kelly, who joined them for the celebrations, shared the joy of the successful claimants. “I am very happy for the families,” Mr Kelly said. “They now have the right to negotiate about exploration, mining and tourism activities on their land.”

In early April, native title holders celebrated native title consent determinations over two pastoral stations and an area including a mineral lease north of Alice Springs at three special sittings of the Federal Court.

Justice Griffiths handed down two non-exclusive native title consent determinations on Aileron Station and one at the Harts Range Racecourse over the whole of Mt Riddock Station, an area of approximately 2,700 square kilometres.

The determinations of native title over the Aileron Station Perpetual Pastoral Lease and the area including the mineral lease known as Nolan Bore took place at Pretty Camp Dam.

They relate to an area of approximately 4,210 square kilometres.

The Aileron native title holders are of the Alhankerr, Atwel/Alkwepetye, Ilkewarn, Kwaty, Mpweringke, Ntyerlkem/Urapentye and Tywerl land holding groups.

Nolan Bore native title holders belong to the Kwaty and Tywerl land holding groups, while the Mt Riddock native title holders belong to the Atwele, IIrrelerre, Ulpmerre and Wartharre land holding groups.

Mr Kelly said all the determinations recognise native title rights, such as the rights to hunt and gather on the land and waters and to conduct cultural activities and ceremonies.

These rights will co-exist with those of the pastoral lessees, who will continue to run the properties as cattle stations.

Source: Land Rights News (August 2017)

2016

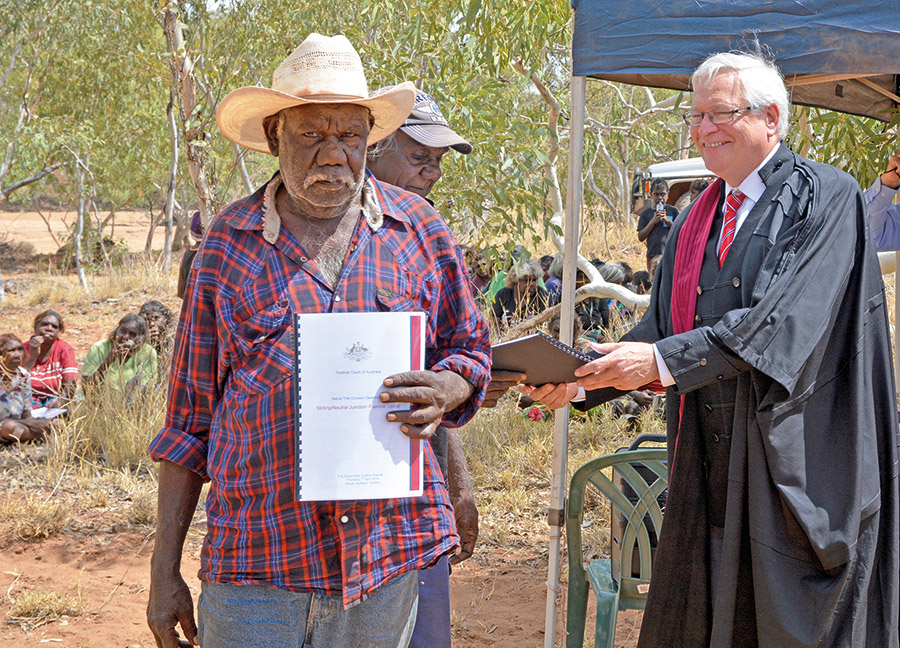

Stirling and Neutral Junction native title recognised at last

Traditional owners of two adjoining pastoral stations north of Alice Springs have received recognition of their right to hunt, gather, fish and conduct ceremonies on their land.

The almost 15,000 square kilometre determination area covers the whole of Stirling Station and parts of Neutral Junction Station.

Justice Reeves made the native title consent determination at a special sitting of the Federal Court on the Hanson River on Stirling Station in April.

The determination also secures traditional owners’ right to negotiate over future exploration and mining.

Anmatyerr and Kaytetye speakers from 13 different landholding groups – Akalperre, Amakweng, Alapanp, Arlwekarr, Arlpawe, Arnerre, Arnmanapwenty, Errene/Warlekerlange, Errweltye, Kwerrkepentye, Rtwerrpe, Tyarre Tyarre and Wake – attended the court sitting.

The Central Land Council filed the native title application in 2011. “The traditional owners were concerned about the protection of sites and wanted to have a say over exploration on their country,” CLC director David Ross said.

The native title rights co-exist with the pastoral leases, which will continue to be run as cattle stations.

The Eynewantheyne Aboriginal Corporation will become the Registered Native Title Body Corporate that holds the rights and interests on behalf of its members.

Source: Land Rights News (August 2016)

Mt Denison and Narwietooma native title celebrations

Special sittings of the Federal Court at two remote Central Australian outstations have confirmed native title for traditional owners of two pastoral properties near Alice Springs.

Justice Rangiah handed down two non-exclusive native title consent determinations at Cockatoo Creek and M’Bunghara outstations in June.

During a sitting at Cockatoo Creek, east of Yuendumu, he recognised native title over the whole of Mt Denison Station, more than 2,700 square kilometres.

The determination at M’Bunghara outstation, one day earlier, was in relation to an area covering the whole of Narwietooma Station, almost 2,700 square kilometres, and a portion of the Dashwood Creek where the claimants proved exclusive possession.

CLC chair Francis Kelly said he hopes the Mt Denison determination will improve the relationship between the traditional owners and the pastoral lease holders.“It will make it easier to share the country,” he said.

Mr Kelly said the court’s determinations recognise the groups’ rights to hunt, gather and fish, as well as to conduct cultural activities and ceremonies on their land. “It also gives them the right to negotiate about exploration and mining.”

These rights will co-exist with the Mt Denison and Narwietooma pastoral leases, which will continue to be run as cattle stations.The Mt Denison native title holders belong to the Rrkwer/Mamp/Arrwek, Yinjirrpikurlangu, Janyinpartinya,Yanarilyi and Ngarliyikirlangu landholding groups.Their native title rights and interests will be held by their Registered Native Title Body Corporate, the Mt Denison Aboriginal Corporation.

The Narwietooma native title holders are Western Arrernte and Anmatyerr speakers and belong to the Imperlknge, Urlatherrke, Parerrule, Yaperlpe, Urlampe, Lwekerreye and Ilewerr landholding groups and people who have rights and interests in the area of land known as Kwerlerrethe.

The Wala Aboriginal Corporation will become the Registered Native Title Body Corporate that holds their rights and interests.

Source: Land Rights News (August 2016)

2014

Native Title for Bushy Park and Kalkarindji

In May it was a big week for native title holders in Central Australia. The Federal Court recognised the native title rights of groups at both Kalkarindji and Bushy Park Station.

The Court sat in Kalkarindji, the birthplace of the modern land rights movement, on 7th May 2014. A determination of native title by consent over the Kalkarindji township was handed down in favour of the local Gurindji people.

Director of the CLC, David Ross, congratulated the traditional owners: “Standing with you here in your country, it is wonderful to see the long and proud tradition of Gurindji people is continuing, fighting for and achieving just recognition of your rights in traditional lands,” he said.

Mr Ross also noted that with the successful outcome of negotiations between the Northern Territory Government and traditional owners, the development of Kalkarindji was well provided for.

Senior traditional owner Roslyn Frith, a director of the Gurindji Aboriginal Corporation, celebrated the persistence of the Gurindji people: “We hold the land in our hands, and recognition here today is another milestone in the continuing campaign for Aboriginal land rights.”

Ms Frith also thanked the Federal Court and the Central Land Council and its staff for their assistance in lodging and pursuing the claim, together with the Northern Territory Government for its consent to the settlement.

Two days later, the court reconvened in a different region, and this time Justice White sat before the native title holders for Bushy Park to consider their claim for recognition over the area covered by the Bushy Park Pastoral Lease.

The Bushy Park PPL Native Title determination application was filed with the Court in December 2012 and on 9 May 2014, the Court recognised the non-exclusive native title rights of the Ilkewarn, Atwel/Alkwepetye and Ayampe landholding groups.

The Judge’s decision was handed down at Edwards Creek, (around 115 kilometres northeast of Alice Springs) and after the court ceremony senior native title holder Eric Penangk told the gathering: “Ceremony and culture has to pass to the young people. Aboriginal law and whitefella law can work together.”

David Ross congratulated the Ilkewarn, Atwel/Alkwepetye and Ayampe native title holders for gaining recognition of their laws from the court, noting that it was one more step in the fight for land rights.

While the native title rights are now recognised they still sit with other laws such as the NT Pastoral Land Act, and Bushy Park will continue to run as a pastoral lease.

Bushy Park PPL is located in the east off the Plenty Highway and covers an area of 1695 square kilometres. The perpetual pastoral lease will continue to run as a pastoral lease.

Source: Land Rights News (May 2014)

2013

Napperby Station native title

The Federal Court has recognised the native title rights of seven estate groups over the Napperby pastoral lease.

Sitting at Laramba Community Living Area on July 2, the court under Justice Reeves recognised by consent the non-exclusive native title rights of the Alherramp/Rrweltya-pet, Ilewerr, Mamp/Arr-wek, Tywerl, Arrangkey, Anentyerr/Anenkerr and Ntyerlkem/Urapentye es-tate groups. The seven groups are Anmatyerr and Arrernte people whose country includes the area where Napperby Station is located.

Napperby will continue to operate as a pastoral lease by the current owners.

The original application was filed with the court in 2005 as a result of a mining company being granted an exploration licence over an area on station of important cultural significance to the native title holders.

The native title holders were anxious to protect these areas of high significance and instructed the CLC to lodge a native tile application over the area.

This application was withdrawn on 17 March 2011 and a new native title application over the whole of the pastoral lease was filed with the court.

Source: Land Rights News (August 2013)

Native Title rights at Mount Doreen

The Federal Court has recognised the native title rights of groups from the Ngaliya Warlpiri people over Mt Doreen Station.

The Federal Court under Justice Reeves determined native title by consent over the Mt Doreen Station Perpetual Pastoral Lease (PPL) at 8 Mile Bore, 400 kilometres northwest of Alice Springs.

The decision recognised the non-exclusive native title rights of the Jiri/Kuyukurlangu, Kumpu, Kunajarrayi, Mikanji, Pikilyi, Pirrpirrpakarnu, Wantungurru, Wapatali/Mawunji, Warlukurlangu, Yamaparnta, Yarripiri and Yarungkanyi/Murrku estate groups, who are part of the Ngaliya Warlpiri people.

The native title claimants’ country includes Mt Doreen Station, but the Braitling family will continue to operate Mt Doreen as a pastoral lease.

CLC Director David Ross congratulated the Ngaliya Warlpiri native title holders and paid tribute to claimants who had passed away during the application process.

An initial application was filed with the Court in 2005 after a mining company was granted an exploration licence over an area of significant cultural importance to the native title holders on Mt Doreen Station.

The native title holders were keen to protect these areas of high significance and instructed CLC to lodge a native title application over the area. This application was withdrawn on 11 October 2011 and a new native title application over the whole pastoral lease was filed with the Court on 14 October 2011

Source: Land Rights News (August 2013)

2012

Lake Nash native title recognised by Federal Court

Native title was declared on two cattle stations near the Queensland border in August.

The basketball court at Alpurruru-lam community temporarily became the Federal Court, which recognised the rights and interests of native title holders of the Lake Nash and Georgina Downs pastoral leases.

The native title application was filed with the court for the Ilperrelhelam, Malarrarr, Nwerrarr, Meyt, Itnwerrengayt and Ampwertety landholding groups in 2001.

The Court recognised their traditional rights, including the rights to access and hunt, gather and fish on the land and waters, conduct cultural activities and ceremonies, and to camp on the land and erect shelters and other structures. The decision also secures their right to negotiate over any future acts such as mining.

Lake Nash and Georgina Downs, approximately 650 kilometres northeast of Alice Springs, are run as pastoral stations. The claimants’ native title rights will coexist with the rights of the pastoral leaseholders to graze cattle.

After a long battle, Lake Nash (Alpurrurulam) became a Community Living Area in 1991, with a small area of land excised from the station to enable traditional owners to live there.

Many of the current claimants or their parents were born and lived on Lake Nash Station near the waterhole for most of their lives.

CLC Director David Ross congratulated the native title holders and paid tribute to the many claimants who passed away during the process.

Native title holders from Glen Helen were also recognised recently.

Source: Land Rights News (December 2012)

Glen Helen Native Title Consent Determination

On 25 September 2012 Justice Lander handed down a native title consent determination at a special sitting of the Federal Court at Hermannsburg community, 120 kilometres west of Alice Springs.

Two applications were originally filed and registered on 23 January 2004 and 3 March 2005 respectively for the purpose of exercising the right to negotiate in regard to future acts on a portion of Glen Helen PPL.

A native title application was later filed on 27 October 2010, replacing the two earlier claims with a single whole of lease claim over Glen Helen Pastoral Lease, which lies approximately 200 kilometres west of Alice Springs.

The determination area lies within the territories of the Tyurretyerenye Western Arrernte and Merinarenye Kukatja-Luritja people.

There are six traditional ‘countries’ on the application area and the groups who hold rights and interests in the Glen Helen area are Imperlkgne, Urlatherrke, Pmerkerterenye, Yaperlpe, Lthalaltweme and Merina people.

The groups acknowledge they have a shared system of laws and customs that applies beyond the application area; however, the decision-making power about a particular country lies with the individual landholding group for that country.

The court’s determination recognises the groups’ traditional rights to access, camp, live on and use the land and its resources, and their responsibility to protect and care for sites and to regulate the land’s access and use by others.

These native title rights will co-exist with the rights of the pastoral leaseholders.

Source: CLC Annual Report 2012-2013

2011

Better protection for Kurundi

The day after sitting at Neutral Junction, the Federal Court visited Injaridjin Waterhole on the Davenport Range National Park, roughly 400 kilometres north of Alice Springs, this time to recognise the native title rights of the traditional owners of the Kurundi Pastoral Lease.

At one of its more picturesque sitting locations, the court recognised the non-exclusive native title rights of the claimants over the 3857 square kilometres of the lease.

The determination – by consent of the parties, as it was at Neutral Junction – is the outcome of a 10-year native title claim made by the Mirtartu, Warupunju, Arrawajin and Tijampara people.

The native title claim-ants have maintained their strong connection to their country on the Kurundi pastoral lease, in sometimes difficult circumstances.

Many of the claimants and their ancestors have lived and worked at the station over many decades. Working as stockmen gave them an opportunity to stay on their country, learning all their stories and abiding by their law.

“Station owns this for grass and water, that’s all – water the bullocks and horses,” said one senior local man. “They only working on top of Aboriginal land – the sacred sites, they (are) all still there.”

Claimant Pilot Carr was born on the end of the Kurundi airstrip and lived and worked as a stockman on Kurundi Station most of his life.

Another, Pat Murphy, was born on the station, and his father, Murphy Jappanangka, worked as a stockman there, later taking part in the Kurundi walk-off for equal wages in 1977.

The claimants hope that the determination will help them to continue to protect their country and sacred sites on Kurundi Station into the future.

“We never forget about our law,” said one claimant. “We work through the land council – we show land council what we got on the ground so they can prove it. “They did prove it – we got title for that now.

“The old people taught us how to look after country and we look after country same way. Before we go, we gotta teach our children same way, they will carry on after we go.”

“Our law is in the ground – it’s a pretty hard law. We gotta understand whitefella law and whitefella gotta understand our law. Sometimes we don’t understand each other.”

Source: Land Rights News (October 2011)

Court sees the truth in landowner’s knowledge

A cold, wet day north of Barrow Creek recently, the Federal Court of Australia recognised the native title rights of the area’s Kaytetye traditional owners.

The ceremony took place at Arnerre, an outstation within the Neutral Junction pastoral lease, which is also the site of a critical cluster of sites sacred to the Kaytetye.

During a rare break in the rain, Justice John Reeves handed down the court’s determination “by consent of the parties”, reflecting the uncontested nature of the claim. It was an important moment for the Kaytetye.

Under the Northern Territory’s Pastoral Lands Act, the traditional owners already had many of the rights that native title recognition brings, including the right of access, hunting, and the right to reside and build shelters.

What they didn’t have was native title’s guarantee of the right to at least negotiate over any future mining or exploration activity on the lands.

The area covers 1664 square kilometres of the northwestern section of the Neutral Junction Pastoral Lease, and includes the parallel Crawford and Osborne Ranges.

Traditional owners have historically resisted any exploration here, and any ground disturbance has caused a high level of anxiety to senior people.

In the early 1990s, CLC asked the Territory minister responsible for mines to declare a Reservation from Occupancy under the Mining Act over a portion of the Crawford and Osborne Ranges in order to protect sacred sites.

Unfortunately the minister refused. At various times the area has been loosely protected by agreements between the CLC and exploration and mining companies not to interfere with the sites, but now the traditional owners hope that recognition of their native title rights will strengthen this protection.

Kaytetye traditional owner and CLC ranger Kim Brown said that the Federal Court’s determination was an important moment for him personally. “It’s a special day and it makes our family proud and happy – we struggled for a couple of years.

Mr Brown also hoped families will start accessing country more. “I reckon people will feel more empowered to come back home now too.”

Tommy Thompson, a senior local man who speaks ten languages, was characteristically philosophical about the win. “Aboriginal native title is really Australian law with other laws coming up. “White laws come over the top of our native title law and our language. “We march on together.”

Source: Land Rights News (October 2011)

Ooratippra win exclusive native title

An native title consent determination for exclusive possession of Ooratippra Station pastoral lease was handed down by the Federal Court in July at Ooratippra pastoral lease some 300 kilometres northwest of Alice Springs.

Ooratippra is a 4,292 square kilometres pastoral lease owned by the Ooratippra Aboriginal Corporation .

The claim was lodged over the whole of the station and also included the Irretety Community Living Area, an area of eight square kilometres held by Irretety Aboriginal Corporation and located within the station boundaries.

Community Living Areas were small areas able to be established for Aboriginal people with historical residential association with stations who were unable to claim their traditional land back under the Land Rights Act.

As Ooratippra Station PPL and Irretety CLA are owned by native title holders, they are able to claim exclusive possession (“to the exclusion of all others”) under the Native Title Act, rather than non-exclusive rights which co-exist with pastoral lessees. That recognition secures their traditional rights, as well as the right to negotiate over any future acts like mining.

The Indigenous Land Corporation purchased Ooratippra Station PPL in May 1999 after years of lobbying by native title holders who wanted title to their own land and to be able to run their own cattle business.

Ooratippra can run up to 4000 head of cattle and will continue to be leased out to a neighbouring land owner who will, over time, assist in the re-establishment of a locally managed cattle herd.

The CLC lodged the Ooratippra native title application on behalf of several hundred native title holders in 2001.

The claim represents the Irrkwal, Irrmarn, Ntewerrek, Aharreng, Arrty/Amatyerr and Areyn estate groups of the Alyawarr language group.

Source: Land Rights News (October 2011)

2004

Native Title Victory

Central Land Council director David Ross congratulated Alyawarr, Kattete, Warumungu and Wakay native title holders on having their native title rights recognised in a decision handed down by the federal courts justice Mansfield.

“The decision recognises native title holders and their strong rights and interest in the area which will allow them to play a strong part in the future joint management of the park,” said Mr Ross.

The Central Land Council lodged a native title application on behalf of native title holders with the National Native Title Tribunal in 1995 over land southeast of Tennant Creek, including the proposed Davenport Murchison National Park and the historic township of Hatches Creek.

The area covered by the application is approximately 1,143 square kilometres and includes land within the Kurundi pastoral lease which was surrendered in 1993 for the proposed Davenport Range National Park.

Also included in the claim is the township of Hatches Creek which is surrounded by the Anurrete land trust.

Hatches Creek was gazetted in 1953, but was a “town” in name only, and at the time of the native title application was vacant Crown land.

Under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act ( Northern Territory National Park ) 1976, areas inside town boundaries are excluded from claim so the area was never included in the

Anurrete Land Trust.

Mr Justice Mansfield of the Federal Court of Australia heard strong evidence from Aboriginal witnesses about their law and connection to the area over two weeks of hearings on country in September 2000.

“It is really sad that a number of these key witnesses have passed away since the hearing ended while waiting for today’s decision,” said Mr Ross

Source: Land Rights News (July 2004)

FREQUENTLY ASKED NATIVE TITLE QUESTIONS

When the British arrived in 1788, they wrongly assumed that the land of Australia was terra nullius (land that belonged to no one). In 1992 the High Court, in its historic Mabo (No 2) decision, ruled that this assumption was incorrect.

The Mabo decision recognised the rights and interests that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people maintained in their land and waters.

The Native Title Act 1993 (Native Title Act) is a law passed by the Australian Parliament that protects those native title rights and interests.

The act describes how to claim native title and how native title is recognised and protected in Australia. It sets out how native title rights and interests fit within Australian law.

Native title is not a new type of land grant but an indigenous common law right that pre-dates European settlement.

Native title is a collection of rights outlined in a native title determination and can vary from determination to determination.

Many native title claims are for rights that are shared with other people who also have an interest in the land, such as the rights to:

- visit and camp on country, including making camp fires

- get water from soakages, waterholes and rivers

- talk about a development proposal and try to make an agreement

- hunt and fish native animals

- get bush tucker, wood, ochre and other natural resources

- look after and protect sacred sites and other important places

- teach and hold meetings and ceremonies on country

- decide how other Aboriginal people can use the country

- take anyone on the country to help with cultural activities and research

In some areas, such as crown land and Aboriginal-owned pastoral leases, the strongest kind of native title rights can be recognised, where native title holders own the land. This is called exclusive possession native title and gives native title holders a right to say what can and cannot be done on that land.

Other people need permission before they can access exclusive possession native title areas.

However, in other areas, such as pastoral leases, shared native title rights do not give Aboriginal people ownership of the land. In those areas, native title holders generally cannot:

- stop people coming on the country

- build houses or make new outstations

- get water from bores or dams built by pastoralists

- light fires to clear country

- stop development

After the Federal Court agrees to a native title claim, the native title holders need to establish a corporation called a prescribed body corporate, or PBC. PBCs manage and protect native title on behalf of the native title holders.

As legal entities, PBCs have certain roles and responsibilities under the following laws:

- Native Title Act 1993 (Native Title Act)

- Native Title (Prescribed Bodies Corporate) Regulations 1999 (PBC Regulations)

- Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (CATSI Act)

- other commonwealth, state and territory legislation

The High Court’s Mabo (No 2) decision in 1992 holds that native title existed everywhere in Australia in 1788 and today may continue to exist where Aboriginal people continue to observe their traditional laws and customs. Its Wik judgment in 1996 determined that native title could coexist with other rights on land held under a pastoral lease. Because of this, native title can usually be claimed on pastoral leases and crown land but not on crown leases or freehold.

Freehold titles and most leases over land extinguish (or finish) native title completely, except for some titles held by Aboriginal people. Aboriginal titles, such as land rights title or Aboriginal-owned pastoral stations, will generally have no effect on native title.

Some land titles will generally extinguish native title completely, but a pastoral lease will only extinguish some native title rights.

An indigenous land use agreement (ILUA) is an agreement created by the Native Title Act.

An ILUA allows developers to make plans and seek consent from native title holders for development on native title land.

It also allows native title holders to negotiate the suppression or extinguishment of their native title rights and interests. Agreements may include employment, compensation and the protection of sacred sites.

Entering into an ILUA is voluntary. It includes full and final compensation to native title holders and must be registered by the Naional Native Title Tribunal.

The government must notify native title holders of any new exploration licence proposal.

If the government thinks the effect on native title will be minor, it can fast-track the proposal. This is usually done for exploration which does not significantly disturb country.

If the fast-track is used, the company does not have to negotiate with native title holders and can carry out the exploration. In our experience, companies are more successful if they voluntarily build relationships with native title holders at the exploration stage.

If the government decides the fast-track does not apply, the company must negotiate with native title holders about its plan.

Native title holders almost always have a right to negotiate with big developers such as mining companies.

If negotiations break down, native title holders cannot veto developments. Instead, the National Native Title Tribunal decides if the project can go ahead or not.

We have been a native title representative body for Central Australia since 1994. Our legal duties include:

- facilitation and assistance

- certification of native title determination applications and ILUAs

- dispute resolution

- notification of native title holders of future act activities

- agreement making

- provision of a process for review of our decisions and actions and publication of that process

For more information go to Native Title Act made simple.

The history of the Native Title Act

The federal parliament passed the Aboriginal Land Rights Act for the Northern Territory in 1976. The act applies only to Aboriginal people with connections to land in the Northern Territory. The other states and territories missed out.

In 1982 Eddie Mabo, from Mer Island in the Torres Strait, complained to the High Court that Queensland didn’t recognise that his people, the Meriam, had a system of law and ownership before British settlement.

In 1992 the court ruled that indigenous traditional title to the land had survived British settlement and called it native title. As a result, Mabo’s people had native title rights over their islands.

The decision meant that native title could survive anywhere in Australia, as long as indigenous people had maintained Aboriginal law and customs on that land and no other titles allowing ownership of that land had extinguished (or finished) the native title.

The Alice Springs native title claim

Nearly 130 years after European settlement (see timeline below) began in Central Australia, the common law of Australia finally recognised the native title rights and interests of the traditional owners of the Alice Springs area.

This decision was the first in Australia to recognise native title in an urban area.