Land won back

More than half the land in our region – approximately 418,000 square kilometres of the southern part of the Northern Territory – is Aboriginal land.

Aboriginal land is private property and its traditional owners hold it collectively, mostly through a unique form of freehold title under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976. This title is inalienable, meaning it cannot be sold or mortgaged. Aboriginal land trusts formally hold the land upon its grant, typically after a land claim. Land trusts have come to refer to this title holding entity and to the land area itself.

The Land Rights Act, a federal law unique to the NT, recognises Aboriginal spiritual affiliation and responsibility as the basis for traditional ownership, by implication dating back indefinitely. Traditional owners have a deep affinity with particular areas of land. Much of their sense of identity derives from it. One area is not exchangeable for another, unlike under Western land systems.

The return of the Uluru—Kata Tjuta National Park under the Land Rights Act to its traditional owners in 1985 was a landmark in land rights history. It was the first time Aboriginal people in Central Australia agreed to jointly manage their land with a federal government agency, Parks Australia. National park joint management is now the norm here.

Another significant milestone is the Warumungu land claim, one of the longest and hardest-fought claims in land rights history. Repeated court challenges from the NT government after the claim was lodged in 1978 meant that it was not heard until 1985. The Aboriginal Land Commissioner hearing it recommended the grant of a large part of the claim area in July 1988. It took another three years before any of the land was granted to its traditional owners and five years before most of it was returned.

Land Rights News has long reported on traditional owners’ efforts to win back their land. Here are some of the stories:

Land Claims

Ammaroo Station handback

Land Rights News – Vol 10, No.1 (Mar 2020)

There were no ceremonies when the Minister for Indigenous Australians and his entourage arrived at Ampilatwatja to mark the handback of a part of Ammaroo Station, after one of the ceremonial leaders had taken ill.

Read More

Yurkurru

Land Rights News – Vol 4, No.2 (Nov 2014)

The 22 year battle for justice by the traditional owners of Yurrkuru (Brooks Soak) is over.

Read More

Barrow Creek Land Claim

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.40 (Jul 1999)

The construction of the Barrow Creek Telegraph Station in 1872, 280 kilometres north of Alice Springs, had a profound impact on the Kaytetye traditional owners of the land. It confronted them with strange new humans, new animals like goats and cows and what was then modern technology.

Read More

Central Mt Wedge back

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.37 (Oct 1995)

News that the 3,244 square kilometre Mt Wedge pastoral lease, some 350 kilometres north-west of Alice Springs, was going up for auction generated a great deal of excitement and interest from its traditional owners.

Read More

Mt Frederick repeat claim won

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.37 (Oct 1995)

Aboriginal freehold title to 2,350 square kilometres of land in the remote Tanami Desert near the Western Australian border benefits traditional owners from three different language groups.

Read MoreSimpson Desert returned to Eastern Arrernte

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.34 (Nov 1994)

Eastern Arrernte people celebrated title to their traditional lands in the northern Simpson Desert on 19 August 1994 when then federal Aboriginal Affairs Minister Robert Tickner granted them nearly 23,000 square kilometres of it at a ceremony at Arkarnenhe Well about 250 kilometres east of Alice Springs.

Read More

The Warumungu land claim campaign

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.32 (Jul 1995)

This claim was one of the longest and hardest-fought in the history of land rights.

Early explorers described the Warumungu people as flourishing in the 1870s, but by 1915 the invasion of their lands that followed the exploration brought them to the brink of starvation.

Read More

Luritja finally seal station deal

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.32 (Apr 1994)

In December 1993 the CLC helped the Tempe Downs Aboriginal Corporation to buy, on behalf of the traditional owners, the neighbouring pastoral leases Tempe Downs and Middleton Ponds, together totalling approximately 4,750 square kilometres.

Read More

Tanami Downs: a new beginning for the “Mongrel” station

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.27 (Mar 1993)

Pastoral lease turned Aboriginal land trust, Tanami Downs – formerly Mongrel Downs – is about 700 kilometres north-west of Alice Springs, right on the Western Australia border.

Read More

Undoolya Bore, Ooratippra and Mt Peachy

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.23 (Jul 1991)

Dispersed as their lands may be, Aboriginal land trust members from Undoolya Bore (10 kilometres east of Alice Springs), Ooratippra (400 kilometres north-east) and Mt Peachy (100 kilometres south) happily came together – in Tennant Creek – to receive their land titles.

Read MoreWestern Desert land claim: handback at Piccaninny Bore

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.23 (Jul 1991)

“We’ve got two titles,” said Yingualyalya Aboriginal Land Trust Chairman Mick Inverway Jungarrayl. “White man’s title and Aboriginal title.”

Mr Inverway was speaking at Piccaninny Bore, 600 kilometres northwest of Alice Springs, following the handback to traditional owners of two areas of land near the Northern Territory-Western Australian border by Aboriginal Affairs Minister Robert Tickner.

Read More

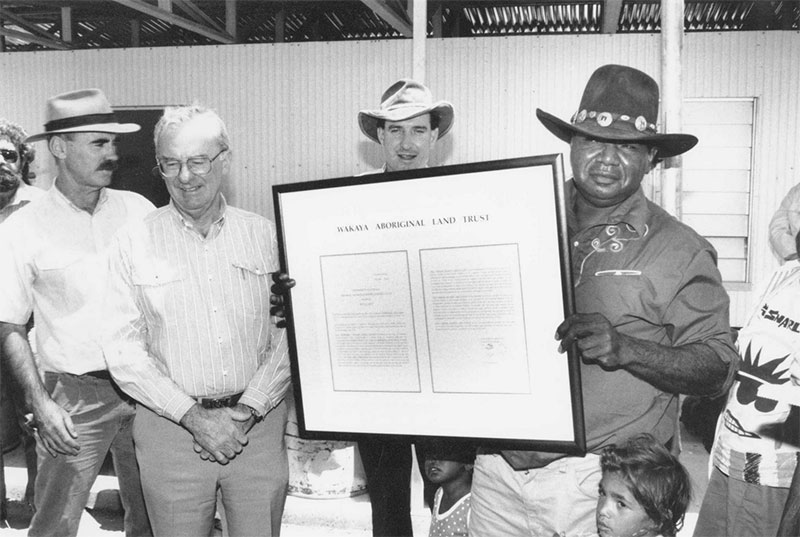

Wakaya Alywarre land claim

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.17 (Feb 1990)

On the eve of the Wakaya/Alyawarre land claim hearing in 1989, the NT government offered the claimants grants of NT title if they dropped their claim under the Land Rights Act.

Read More

Mt Allan – NT withdraws action

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.17 (Feb 1990)

In 1990, the NT government withdrew legal action over the grant to traditional owners of Mount Allan Station, 240 kilometres north-west of Alice Springs, and agreed to pay the CLC’s legal costs. An injunction restraining the Registrar-General from registering the title deed, the final step in securing Aboriginal freehold land, usually something of a formality, was lifted.

Read More

Taxpayer millions believed wasted in claim appeals

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.14 (May 1989)

In the wake of a Federal Court decision on Mt Allan, the CLC challenged the NT government to reveal how much it had spent fighting land claims.

Read More

Talking history: Murphy Japanangka at McLaren Creek

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.11 (Nov 1988)

I grew up with horses and cattle. I was working at Kurundi station.

I did everything – droving, branding, mustering, breaking horses, fencing, making a yard, everything.

Read MoreChilla Well win to traditional owners

Land Rights News – Vol 2 No.10 (Sep 1988)

The Federal Court dismissed an appeal by the NT Government against a land grant to the traditional owners of Chilla Well about 400 kms north-west of Alice Springs on the edge of the Tanami Desert. The government had submitted that there was a public road on the claim area. The Land Rights Act prevents claims over public roads.

Read More

Warlpiri, Kukatja and Ngarti land claim

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.2 (Mar 1987)

The Warlpiri, Kakatja and Ngarti land claim was the eleventh presented by the CLC under the Land Rights Act on behalf of traditional owners. In all land claims, the presentation of the case before the Aboriginal Land Commissioner was the culmination of a long process of CLC research into and consultation with the traditional owners of the land. It was for the Land Commissioner to consider the evidence presented, and other relevant matters, and decide whether or not to grant the land.

Read More

Mt Barkly land claim

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.2 (Mar 1987)

The Mt Barkly claim was the first time Aboriginal people had used the Land Rights Act to claim a previously purchased pastoral lease, necessary to convert the lease to Aboriginal freehold title.

Read More

Daguragu station land claim

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.2 (Nov 1986)

The courageous actions of the Gurindji people in their demand for land rights took the realities of decades of oppression of and colonial injustice to Aboriginal people into the sitting rooms of urban Australia.

Many heard and saw on television for the first time Aboriginal people telling of their exploitation by the pastoral industry.

Read More

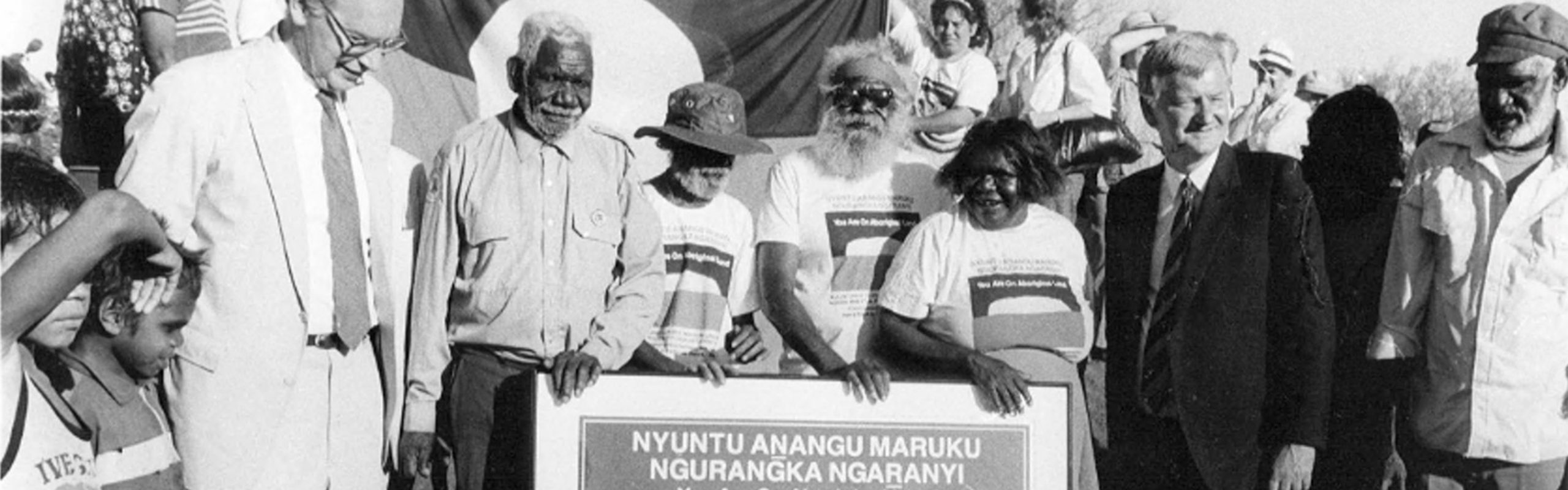

Uluru—Kata Tjuta land claim

Land Rights News – Vol 2 N.1 (Nov 1985)

In November 1983, Labor Prime Minister Bob Hawke announced that Uluru—Kata Tjuta National Park would be returned to its traditional owners. This was land that the Aboriginal Land Commissioner could not recommend for grant under the Land Rights Act because it had already been alienated as a national park.

Read MoreAmmaroo Station handback

Land Rights News – Vol 10, No.1 (Mar 2020)

There were no ceremonies when the Minister for Indigenous Australians and his entourage arrived at Ampilatwatja to mark the handback of a part of Ammaroo Station, after one of the ceremonial leaders had taken ill.

Instead, Ken Wyatt and the traditional owners gathered with their guests around the edges of the basketball court on November 6, silently remembering those who had passed away during the long wait.

Mr Wyatt had flown into the remote community a few hours earlier to return a slice of station land to the adjoining Aherrenge Aboriginal Land Trust, and paid tribute to past elders.

“Their guidance was important in reaching this point today because their wisdom and knowledge of country played a major part in what has been achieved,” he said.

He spoke of their “enduring perpetuity of connection” with the approximately 31 square kilometres of pastoral lease land in the Sandover region he was adding to the land trust.

“It is country that has been looked after, lived on and travelled since time immemorial. It is a place with important sites, stories and ceremonies that keep the land alive today,” he said.

“Knowledge of country, stories and ceremonies have been passed from generation to generation. By having your land as yours you’ll continue that tradition and continue to build on the strength of who you are and your spiritual and cultural connection to land.”

After he handed over the framed title deeds, Mr Wyatt commented on “the absolute joy in the faces of the elders and those who started the journey some time ago”.

One of them was Nigel Morton.

“The land is ours, it has always been ours, we have the rights and [now] we have proof of that,” Mr Morton told CAAMA.

“The title that has been given back to us is so significant to our song lines, the emu and the red kangaroo. Going back to the old days, before we had funerals, that’s where our tribal burial grounds are too.

“Our elders wanted this to happen during their time, but this took so long and most of them passed, that’s the saddest part.”

Yurkurru

Land Rights News – Vol 4, No.2 (Nov 2014)

The 22 year battle for justice by the traditional owners of Yurrkuru (Brooks Soak) is over.

During a ceremony on 8 September at Yurrkuru near Yuendumu, Indigenous Affairs Minister Nigel Scullion handed the title to the Yurrkuru Aboriginal Land Trust to Willowra elder and CLC executive member Teddy Long, on behalf of the traditional owner group.

The square mile of former crown land surrounded by the Mt Denison pastoral lease includes the sacred site where dingo trapper Fred Brooks was killed by Aboriginal men in 1928, before Mr Long was born.

The killing triggered a series of reprisal killings of large numbers of innocent Aboriginal people across the region by Constable George Murray. The raids became known as the Coniston Massacre.

“My father explained to me what happened here in the shooting days,” Mr Long said.

“He explained every rockhole and soakage where people got shot.”

The Aboriginal Land Commissioner recommended the grant of the block in 1992, but the Mt Denison pastoralists bitterly opposed it.

“I am happy to have my grandfather’s and father’s country, even though it took a long time,” Mr Long said. “It’s important for ceremony and culture.”

Mr Long and the men sang a ngatijiri (budgerigar) song while the women (pictured at left) performed a bandicoot purlapa (song and dance) and presented the Minister with a coolamon and clap sticks.

About 80 traditional owners attended the ceremony.

“They had to wait a long time for their land but they never considered giving up,” said CLC chair and Coniston documentary maker Francis Kelly.

Originally, the traditional owners wanted to set up an outstation on the block, but changed their minds because the soak is an unreliable water source and has been fouled by cattle.

They have plans to build a shelter to harvest rain water and provide shade for visitors, as well as feature interpretive materials about the events that led to the massacres.

“Yurrkuru doesn’t only hold deep cultural significance for us but the loss of so many people during the massacres is still causing a lot of sadness across our region,” Mr Kelly said.

“It will be good to be able to teach visitors about this place so we can make peace with our shared past.”

Barrow Creek Land Claim

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.40 (Jul 1999)

The construction of the Barrow Creek Telegraph Station in 1872, 280 kilometres north of Alice Springs, had a profound impact on the Kaytetye traditional owners of the land. It confronted them with strange new humans, new animals like goats and cows and what was then modern technology.

The Kaytetye still tell the story of an old man and his first encounter with the ‘singing wires’ of the telegraph line. He listened to the humming wires, thinking that bees were alerting him to honey, ‘sugarbag’, inside the poles. When he chopped down the pole he instead found iron inside. He said it made an exceptional tomahawk.

A permanent settlement with stock put heavy pressures on Kaytetye water and food resources and, in early 1874, the police stationed an officer at Barrow Creek to prevent cattle killing.

A week later, in apparent response to theft of their land and exploitation of their women, a group of Aboriginal men descended from the hill behind the telegraph station and fatally speared the station master and a linesman. Reprisal was swift and severe and many innocent Aboriginal people were killed in the following months.

Traditional owners showed the Aboriginal Land Commissioner, Justice Howard Olney in this case, what they say is the birthplace of the Kaytetye language and culture during the land claim hearing at Barrow Creek. More than 30 claimants took part in the hearing, visiting many sacred sites in the area with Justice Olney.

The claim covered some 12.5 square kilometres of land around the telegraph station, including the old racecourse nearby, the Thangkenharenge Resource Centre and the old telegraph station itself but not the Barrow Creek Hotel.

Claimants said they would remain on the land and build houses if the claim was successful. They hoped that secure title would enable them to get funding for the houses and essential services, a hope not diminished since success in the claim and the subsequent grant of the land to the traditional owners on 27 August 2002.

Central Mt Wedge back

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.37 (Oct 1995)

News that the 3,244 square kilometre Mt Wedge pastoral lease, some 350 kilometres north-west of Alice Springs, was going up for auction generated a great deal of excitement and interest from its traditional owners.

As a result of CLC negotiations on their behalf, the sale of the property to the Ngarlatji Aboriginal Land Corporation was finalised with funding from the Aboriginal Benefits Trust Account.

About 150 traditional owners of Mt Wedge, many living at Laramba, Yuendumu and Mt Allan communities, were looking forward to moving back to their country. They have always maintained strong ties to it.

The establishment of Karrinyarra outstation on the cattle station against vigorous opposition from the NT Cattleman’s Association was an inspiring testament to their resolve.

Spectacular Mt Wedge the landmark runs straight through the property and water is relatively plentiful.

The traditional owners gave instructions to the CLC to lodge a land claim over their newly acquired property in order to convert its tenure to inalienable Aboriginal freehold title.

Mt Frederick repeat claim won

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.37 (Oct 1995)

Aboriginal freehold title to 2,350 square kilometres of land in the remote Tanami Desert near the Western Australian border benefits traditional owners from three different language groups.

The title to the Mt Frederick (No 2) Land Trust was granted to the traditional owners in September 1995.

The land is linguistically diverse, in part because of its extraordinary, sometimes violent history over the past 100 years.

Pastoral and gold mining activities have had an enormous impact on the lives of the traditional owners since the 1880s. Government Resident reports, settler biographies, local histories, Aboriginal oral traditions and the personal experience of older claimants all attest to the brutality perpetrated.

By 1944, the decline in the number of Aboriginal people in the region prompted the Vestey Group to initiate a plan to provide a labour force for the group’s network of cattle properties in the NT’s north-west.

The station labour recruitment plan moved people out of this claim area. The older claimants tell of working for brutal station managers, of cattle killing, goat stealing, being arrested and seeing relatives shot.

Such forced demographic changes contributed to the linguistic diversity of the claimants, in turn contributing to complexities in the claim research. First lodged as part of the Western Desert Land Claim in 1980, research was made more difficult by the poor access to the claim area resulting from its inhabitants’ removal.

It was not until Tanami Downs to the south was acquired for Aboriginal people, and mining companies graded better roads through the area, that access became easier and the CLC was able to firm up understanding of traditional ownership.

A repeat claim was lodged and was accepted by the Aboriginal Land Commissioner in September 1994, and an offer to settle the claim was made by the NT government late the following year.

The Tanami and Granites gold mines are both close. An exploration agreement between goldminer North Flinders Mines and the traditional owners had already been signed under the provisions of the Land Rights Act in anticipation of the land being granted Aboriginal freehold title.

The agreement guaranteed protection for sacred sites and employment opportunities for Aboriginal people. It was the first such agreement signed by the CLC on behalf of traditional landowners over land still under claim yet with mutual certainty attained in anticipation of the land grant.

Mr Tilmouth said “Aboriginal people are not averse to mining but the are concerned about the protection of their sacred sites. This agreement, signed under Section 48A of the Land Rights Act, gives both the traditional owners and the mining company certainty for the future.”

Simpson Desert returned to Eastern Arrernte

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.34 (Nov 1994)

Eastern Arrernte people celebrated title to their traditional lands in the northern Simpson Desert on 19 August 1994 when then federal Aboriginal Affairs Minister Robert Tickner granted them nearly 23,000 square kilometres of it at a ceremony at Arkarnenhe Well about 250 kilometres east of Alice Springs.

Around 180 people attended the ceremony, including many traditional owners who travelled long distances. An enormous cake was made especially. Eastern Arrernte people had been waiting for the return of this land since the original claim for it was lodged in 1980. It was the first large part of their land returned. The claim actually formally covered two parts: the North Simpson Desert (17,700 square kms) and the North West Simpson Desert (5,250 square kms).

“Eastern Arrernte people were subjected to typically horrific government regulations since first contact with Europeans,” then CLC Director Tracker Tilmouth said.

“The South Australian parliament passed laws to remove and pacify any Aboriginal people likely to impede European expansion. Pastoralists and miners moved quickly and by the late 1800s lease applications covered much of Eastern Arrernte land.”

Mr Tilmouth explained that, upon claim, this land was vacant Crown land, except a 4,000 square kilometre area called Apiwentye, formerly Atula Station, owned and successfully operated by Aboriginal people since 1989.

“Many of the traditional owners returned from a number of areas including Mount Isa and Alice Springs for the handover ceremony,” Mr Tilmouth said.

“Elders are now able to return to the lands of their grandmothers and grandfathers after such long periods away.”

Mr Tickner described the area as harsh by the standards of most Australians, but of enormous significance to the Eastern Arrernte, who were among the most dispossessed Aboriginal people of the NT yet who had maintained cultural links to the land.

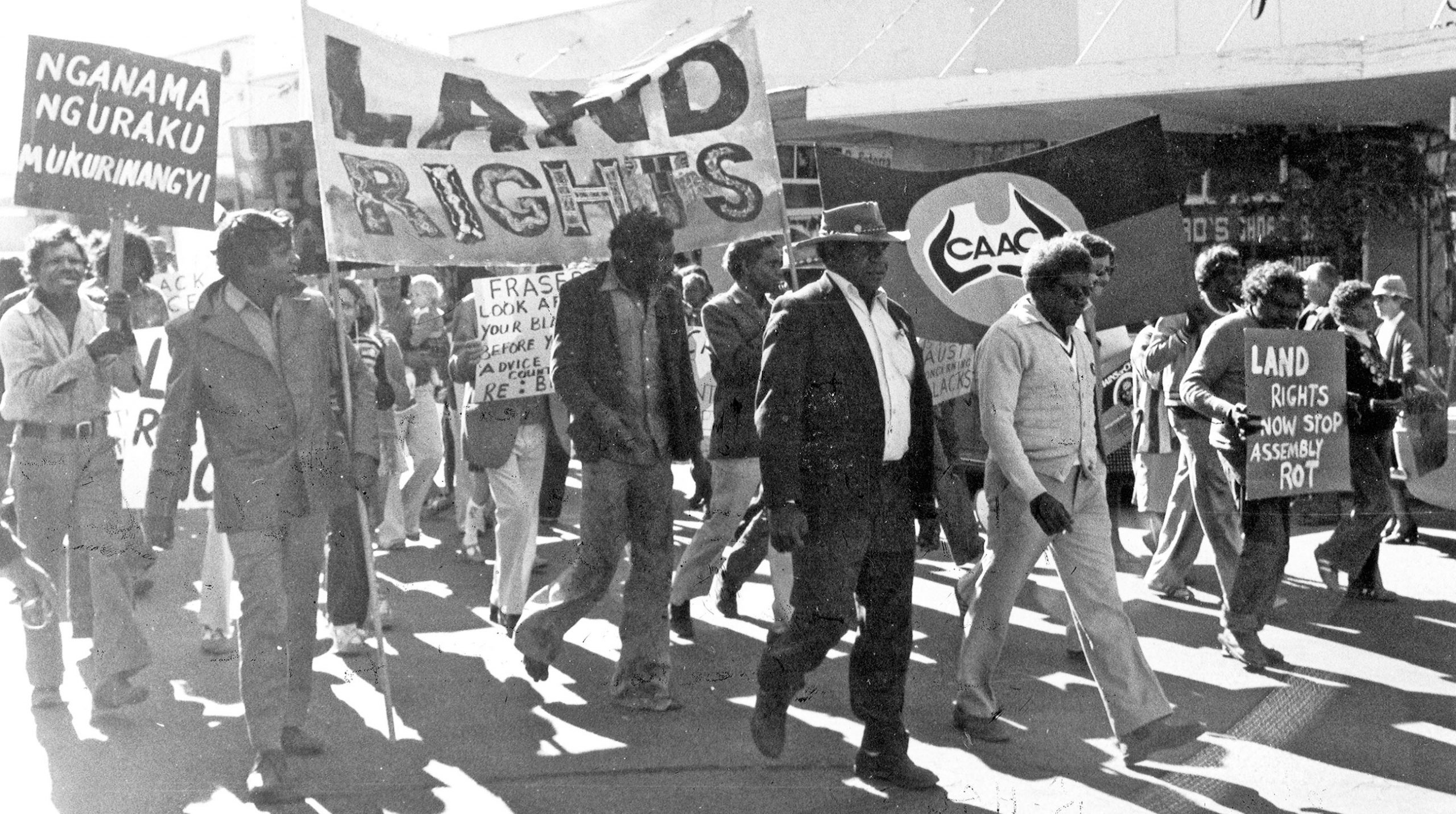

The Warumungu land claim campaign

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.32 (Jul 1995)

This claim was one of the longest and hardest-fought in the history of land rights.

Early explorers described the Warumungu people as flourishing in the 1870s, but by 1915 the invasion of their lands that followed the exploration brought them to the brink of starvation.

The reserve set aside for the Warumungu in 1892 was revoked in 1934 to make way for gold prospectors. They were then shunted to new reserves which later revoked too, until the 1960s when they were pushed off their traditional land altogether.

But the Warumungu wouldn’t give up. They made their first written application for land in 1975 when the Rockhampton Downs Aboriginal community requested land be returned to run their own affairs.

The CLC lodged a claim under the Land Rights Act on behalf of the Warumungu in 1978.

The NT government tried to prevent the claim from proceeding by changing the status of the land. Land within town boundaries could not be claimed, so in the same year the claim was lodged the government extended the boundaries of nearby Tennant Creek town to encompass 750 square kilometres, the size of a major city.

Alienated land – land sold or leased from government – likewise could not be claimed, so in 1982 the NT government leased nine of the twelve areas under claim to a government-controlled corporation, a cynical move it announced two days into the claim hearing that year.

The resulting litigation went all the way to High Court, meaning the hearing didn’t resume until March 1985.

Aboriginal Land Commissioner Justice Michael Maurice recommended the grant of a large part of the claim in July 1988 – ten years after the claim was lodged.

It was another three years before any part of the claimed land was actually granted to its traditional owners and five years before most was returned to them. Although recommended for grant, the Warumungu were required to negotiate over the land with other users, such as the Tennant Creek Town Council, pastoralists, businesses and the NT government, to ensure the interests of these users weren’t adversely affected.

Luritja finally seal station deal

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.32 (Apr 1994)

In December 1993 the CLC helped the Tempe Downs Aboriginal Corporation to buy, on behalf of the traditional owners, the neighbouring pastoral leases Tempe Downs and Middleton Ponds, together totalling approximately 4,750 square kilometres.

More than 350 traditional owners who lived or intended to live on their land directly benefited from the purchase. Preliminary CLC land claim research, for a claim necessary to then convert the land to Aboriginal freehold title, pointed to a total of more than 500 people with traditional affiliations to the area.

At the time, the purchase was considered to be the single most important in the CLC region.

It was a long-awaited victory for the traditional owners who had incorporated the Luritja Land Association in 1974, the first Aboriginal land rights organisation in Central Australia, formed in fact before the CLC and land rights law in the NT.

Even before that, the traditional owners, led by Bruce Breaden who would become chair of the CLC, sought help to purchase Tempe Downs in 1973 when the property was actually offered for sale to the federal Department of Aboriginal Affairs (DAA).

Apparently failing to see the wider significance of the land to traditional owners, the DAA rejected the offer on the grounds that parts of the lease were considered non-viable for a cattle enterprise and were being considered for a national park. Five successive federal ministers for Aboriginal Affairs were approached for help to purchase the land, while the position of the Adelaide-based owners shifted to one of reluctance to sell.

On many occasions the traditional landowners attempted direct action to return to their country, but were thwarted by sometimes severe harassment from station management.

Meanwhile, some 800 square kilometres of Tempe Downs was indeed acquired for the Kings Canyon (Watarrka) National Park in 1983.

Elder Ben Clyne expressed the traditional owners’ extreme frustration and mistrust felt towards the NT government responsible for creating the park: “For 10 years we’ve been asking quietly, ‘Can we have some land? Here? Here? Here? Or where?’ And all the time it’s the same, they say ‘No you can’t have it.” This time we’re being told it’s for tourists. Before it was for cattle. All the time it’s the same. We can’t go on any longer like this.”’

While three groups were able to obtain tiny living areas within the park, only one living area was successfully negotiated on the pastoral lease. The four totalled only 2.75 square kilometres!

“When they made the park we got a small area to live. This one is a small one you know, you can’t run your horses. I’ve had to feed the horses, buying hay and all that,” Mr Breaden said. The horses were to be part of a tourist trail ride enterprise associated with the national park, but with insufficient land for feed the enterprise couldn’t proceed.

However, since the purchase of both properties the future is looking considerably brighter.

“It’s a good thing for me now, for other people too,” said Mr Breaden. “I can run my horses, and we’re looking forward to getting cattle at Tempe Downs too. We want to get steers for a start, for a couple of years, to see how we get on and then if it goes all right we might get breeders. And we’ve got about seven outstations there now, trying to go back and stop there.

“People are very happy. There’s a lot of traditional owners – we purchased it for the whole lot, all the traditional owners. We might get a school at Tempe Downs later on. That’s a long way away though. First we need proper houses, not tin sheds, but fixed houses. We need bores as well.

“That’s pretty good, for kids especially, for the next generation. I think they’ll have a very different life from us. They might have different ideas. They won’t have the struggle we older ones have had all our lives. They’ll be all right. They’ll be able to go ahead and do the work they like.”

By then the preliminary research had commenced for the land claim over the purchased leases. For Mr Breaden, who was born there and worked on both Tempe Downs and Middleton Ponds as a young man, this work couldn’t begin soon enough.

“I want to see the work start now. I want to do something straight away. I’m not ready to retire yet. I want to run the cattle – I’m still a bit lively! I still ride horse and I’m still all right.”

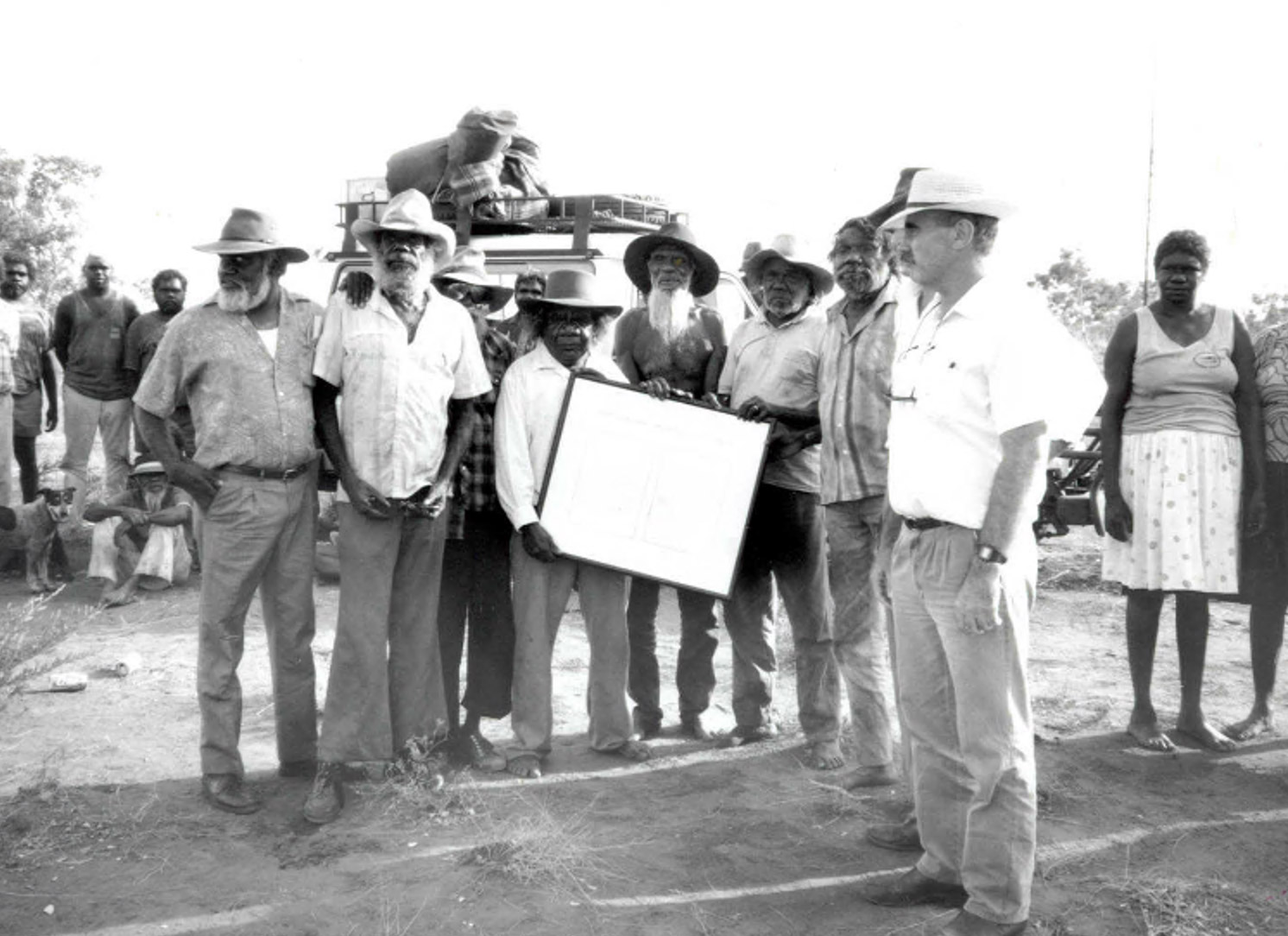

Tanami Downs: a new beginning for the “Mongrel” station

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.27 (Mar 1993)

Pastoral lease turned Aboriginal land trust, Tanami Downs – formerly Mongrel Downs – is about 700 kilometres north-west of Alice Springs, right on the Western Australia border.

It is virtually surrounded by Aboriginal land. To the north and east is the Central Desert Aboriginal Land Trust and to the south the Yiningarra Aboriginal Land Trust.

The station was purchased for the traditional landowners with Aboriginal Development Commission funds in early 1989. Soon after, the CLC lodged a land claim over it on the traditional owners’ behalf. Aboriginal Land Commissioner Justice Olney heard the claim in late 1990 and issued his report in 1992 recommending grant of Aboriginal freehold title to the land.

The land ranges from poor to excellent cattle country. Although droughts are common, Tanami Downs has some mountainous areas with permanent water and the central and northern portions are plains covered with ‘neverfail’ grass, claypans and lakes, providing the basis for cattle operations. Upon purchase, the station was running about 3,500 head of cattle.

In non-Aboriginal terms, it is very isolated. But from some 22,000 years ago till 1945, the area was a focus for large ceremonial meetings in favourable seasons.

Encroachment by the pastoral industry began to force the traditional owners away. Their flight was speeded by gold rushes to the Tanami and Granites mines in 1911 and 1932, each adding severe stress on the Aboriginal peoples’ water and food resources.

The dire drought of 1929-31 might have been the final straw. By 1945 most Aboriginal people were gone from the claim area. Some fled to cattle stations over the border in Western Australia, to appalling living and working conditions.

Though later threatened with eviction from some stations, many managed to stay near Gordon Downs and build a community at Ringer Soak, still home to some Tanami Downs claimants. Other traditional owners were taken to ration depots at the mines and Balgo Hills during the 1940s and were later transferred to larger settlements under government Aboriginal assimilation policies.

Attempts to establish a reserve for Aboriginal people failed because of the influence of mining interests.

The upshot of their profound dislocation was traditional landowners of Tanami Downs and vicinity scattered extraordinary distances over the NT and north-east Western Australia. As well as Ringer Soak, many live or have lived in Balgo, Halls Creek and Kununurra in Western Australia, and at Lajamanu, Yuendumu, Katherine, Tennant Creek and Alice Springs in the NT.

The Tanami Downs cattle operation has continued under the direction of a management committee of traditional owners. In recommending grant of freehold title to the land, Justice Olney said that about 500 claimants would be quite directly advantaged and a further 500 would benefit, primarily from being able to protect sacred sites and their cultural identity. This includes in the face of ongoing mining pressures. The area remains highly prospective.

True to its original non-Aboriginal name, the formality of the title handover ceremony was disrupted by some snarling and snapping from the station dogs, adding humour and a few jokes to the occasion.

The old name implied a place of poor quality and little value, but that was certainly never the way the true owners saw it. With security of title, Tanami Downs is now what the traditional owners make of it.

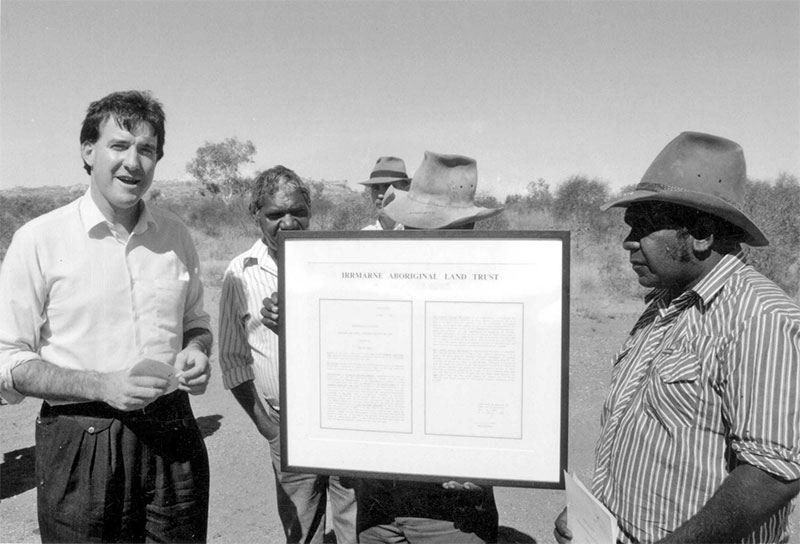

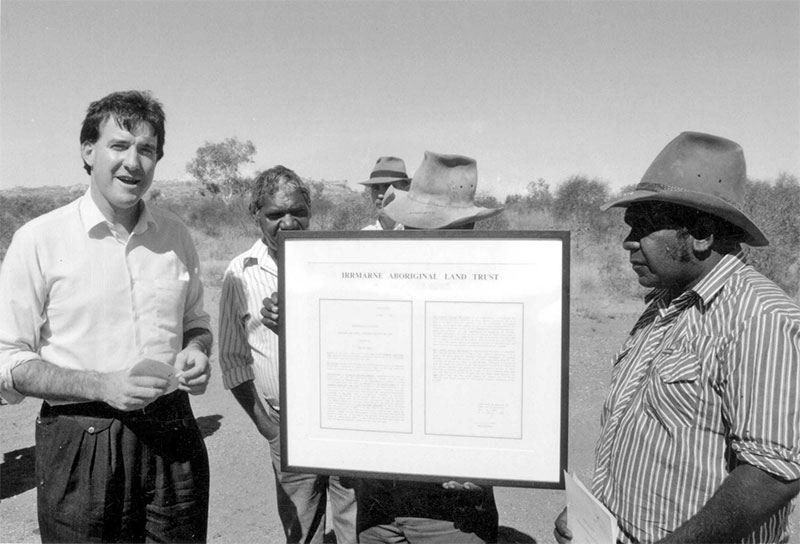

Undoolya Bore, Ooratippra and Mt Peachy

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.23 (Jul 1991)

Dispersed as their lands may be, Aboriginal land trust members from Undoolya Bore (10 kilometres east of Alice Springs), Ooratippra (400 kilometres north-east) and Mt Peachy (100 kilometres south) happily came together – in Tennant Creek – to receive their land titles.

Senior Arrernte man Patrick Hayes accepted title to Undoolya Bore on behalf of the Melknge Aboriginal Land Trust. The Hayes family had been living on the area since 1984 when, frustrated at being unable to obtain tenure to their traditional country through negotiations, they began squatting with nothing more than a few tents.

Sid Kenny accepted the title for Mt Peachy on behalf of his father Jack, then chair of the Mpwelarre Land Trust. Jack Kenny, also an Arrernte elder, was born at Mr Burrell south of Mt Peachy and moved back out to his country in 1981.

Jack’s daughter Mary Ross said that her parents moved out to Mt Peachy to escape living conditions in Alice Springs. “I don’t think they would have survived in town,” she said. “They were that used to being out bush and then they came in. They tried living in town but mum was getting sick all the time and dad just felt like he was in the middle of everything. They wanted to get out.”

Until 1988, Jack lived in a makeshift shed at Mt Peachy and carted water there from Walkabout Bore two kilometres away.

The Ooratippra land claim was lodged on behalf of Alyawarre people in 1980. The traditional owners were scattered from the area in conflicts with hostile pastoralists in the 1920s and 1930s.They were forced to move hundreds of kilometres, generally east to Lake Nash and even Camooweal in Queensland. Roy Rusty as chair of Irrmane Aboriginal Land Trust and his son Stuart accepted the title to this claim area. The traditional owners planned to fence their land trust, the largest of the three small but important areas receiving title, this one expected to provide a living area for about fifty people.

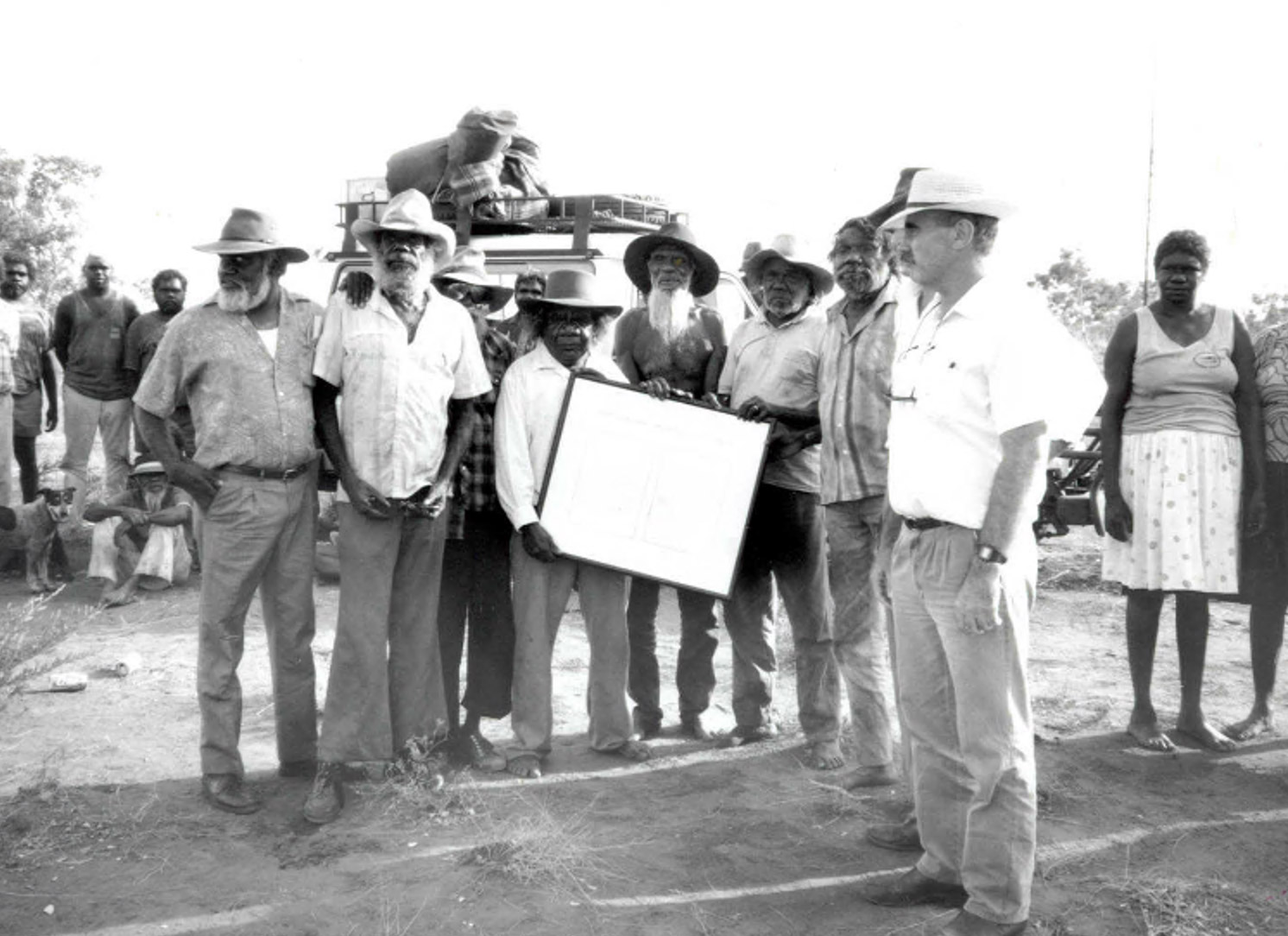

Western Desert land claim: handback at Piccaninny Bore

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.23 (Jul 1991)

“We’ve got two titles,” said Yingualyalya Aboriginal Land Trust Chairman Mick Inverway Jungarrayl. “White man’s title and Aboriginal title.”

Mr Inverway was speaking at Piccaninny Bore, 600 kilometres northwest of Alice Springs, following the handback to traditional owners of two areas of land near the Northern Territory-Western Australian border by Aboriginal Affairs Minister Robert Tickner.

“I’m very pleased to see the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs coming from Alice Springs and a long way,” said Mr Inverway. “Coming here to Piccaninny Bore and he handed over that title. That’s very good! We got the land back. We’ll be able to look after that place.”

The original claim over the area was lodged by the Central Land Council on behalf of the Gurindji, Nyininy and Warlpiri traditional landowners in 1980. The two areas returned cover 3,682 square kilometres.

Popeye Jangala, the chair of the Mount Frederick Aboriginal Land Trust, said he was glad to win non-Aboriginal title to his traditional country. “I’ve been walking all over this country – Wave Hill way, Lajamanu way, Balgo way – a big country. I’m going to stop here now. I’ll stay here. This one.”

The area was first visited by non-Aboriginal people in 1856, when explorer A.C. Gregory earmarked it for cattle grazing.

More permanent non-Aboriginal occupation grew out of prospecting in the early 1900s, sparking killings between Aboriginal people and miners. Central Land Council director David Ross said that the return of the land is a measure of the strength of the traditional landowners bond with their country.

“Despite the harshness of this desert country and the brutal history of their contact with non-Aboriginal people over the last 120 years, the traditional landowners have kept their culture strong.”

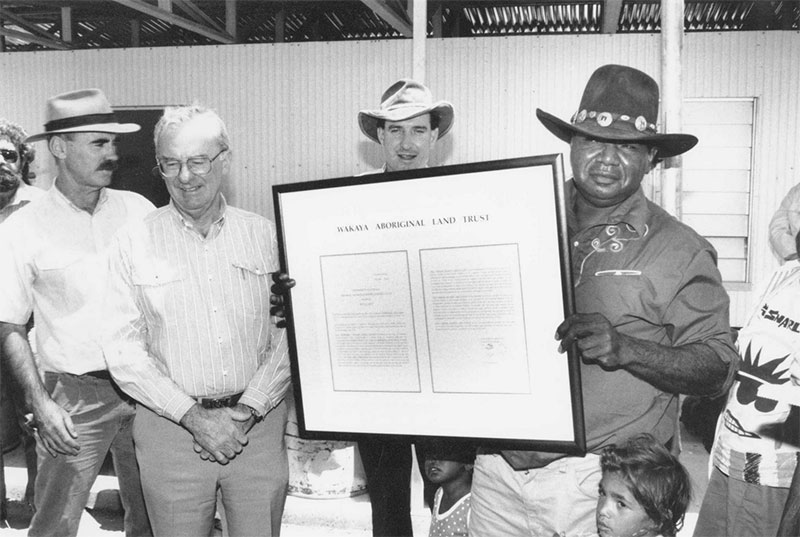

Wakaya Alywarre land claim

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.17 (Feb 1990)

On the eve of the Wakaya/Alyawarre land claim hearing in 1989, the NT government offered the claimants grants of NT title if they dropped their claim under the Land Rights Act.

Eight of the nine claimant groups rejected the offer, preferring to proceed with the claim in the hope of gaining the much stronger Aboriginal freehold title afforded by the Land Rights Act. The NT title did not give landowners control over mining and other development projects, or indeed much control over mere access to their land.

Director of the CLC at the time, David Ross, criticised the NT government for its last minute bid to prevent the land claim proceeding, questioning the sincerity of the government in offering land to the groups or it would have made the offer years earlier.

“The Wakaya/Alyawarre land claim was lodged in 1980,” he said, “Since then thousands of dollars have been spent researching and preparing the claim.” CLC money; CLC and traditional owner time spent.

“The NT government’s record in opposing land rights is well known,” Mr Ross added.

Jack Punch and his family accepted and received NT title to about 5,000 square kilometres of their group’s traditional estate in the desert east of Tennant Creek.

Mt Allan – NT withdraws action

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.17 (Feb 1990)

In 1990, the NT government withdrew legal action over the grant to traditional owners of Mount Allan Station, 240 kilometres north-west of Alice Springs, and agreed to pay the CLC’s legal costs. An injunction restraining the Registrar-General from registering the title deed, the final step in securing Aboriginal freehold land, usually something of a formality, was lifted.

The CLC lodged the claim on behalf of the traditional owners in 1979.

The government had appealed to the full bench of the Federal Court after a judge of the court dismissed its application to have a number of inter-station tracks declared public roads and excised from the land grant.

In October 1988, senior traditional owner Frankie Japanangka received the title to Mount Allan for the Yalpirakinu Aboriginal Land Trust. This had been delayed for more than three years by initial NT government legal action, despite the federal Minister for Aboriginal Affairs announcing in 1985 that he had accepted the recommendation to grant from the Aboriginal Land Commissioner.

But within days of Mt Allan becoming Aboriginal freehold land, the NT government slapped an injunction on the Registrar-General, preventing registration of the deed and allowing time for its latest legal action.

The government’s back down and withdrawal of this legal action followed a meeting between the traditional owners and neighbouring stations at which pastoralists were assured that there would be no impediment to their use of the inter-station tracks.

No impediment in fact had always been the position of the traditional owners and the CLC.

The government agreed to pay more than $36,000 in legal costs to the CLC. The total cost to the NT taxpayer was an estimated $100,000 – all over some dirt tracks that the neighbouring pastoralists themselves were hardly concerned about.

Taxpayer millions believed wasted in claim appeals

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.14 (May 1989)

In the wake of a Federal Court decision on Mt Allan, the CLC challenged the NT government to reveal how much it had spent fighting land claims.

“I estimate more than $5 million has been spent running to court trying to stop the return of land to Aboriginal people,” then CLC Director Pat Dodson said.

Mr Dodson’s challenge followed Federal Court Justice Lockhart’s decision concerning Mt Allan Station, claimed in 1979 then in fact granted Aboriginal freehold title. Justice Lockhart dismissed the NT’s application to have some inter-station roads excised from the land grant and ordered the NT to pay costs, before the NT appealed.

“This Mt Allan case involved five barristers, including two QCs, spending four days in a Sydney court,” said Mr Dodson. “Legal fees alone would be $40,000.Then there’s the cost of flying witnesses down from Mt Allan and Darwin and of course all the preparatory work.

“All that in a failed attempt to have ten dirt tracks declared public roads and cut out of the land grant. The Mt Allan case is only the latest, and compared with the litigation costs involved in the Kenbi and Warumungu land claims, it’s chickenfeed.

“Ever since the Land Rights Act came into force the NT government has shamelessly fought tooth and nail trying to deny Aboriginal people land rights. Everyone has a right to their day in court, but the NT’s rabid activity is bordering on the absurd.

“They’ve raced off to court thirty times against Aboriginal people and are yet to win a case. Obviously the government’s political motivation is clouding their assessment of the legal issues, but of greater concern is the extravagant waste of public money.

“I challenge the NT Attorney General to reveal to taxpayers the full cost of the government’s continuing lit

Talking history: Murphy Japanangka at McLaren Creek

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.11 (Nov 1988)

I grew up with horses and cattle. I was working at Kurundi station.

I did everything – droving, branding, mustering, breaking horses, fencing, making a yard, everything.

We had no motor car, no buggy, nothing. Just horses. We grew up with horses. That droving job was hard work. We were droving from Kurundi to Queensland and also to Alice Springs. It took 5 or 6 weeks to take them down to Alice Springs for trucking. It’s a long way and you had to watch the cattle at night.

There was no yard and maybe five, six or seven hundred cattle and five men. We used pack horses. Pack them up every morning, pull them up for dinner and again at night to make camp.

And in the morning pack them up again. You’ve got to be a good man to ride horses every day. Big work and little money.

We been working for tea, shirt and hat, no good money. I been working there at Kurundi for a long time – since I had no whiskers.

When the army came through (World War 2) we were working there. When the army finished, we were still working there. We didn’t have houses. No houses, no sheet of iron, nothing like that. We just had humpies, grass huts, that’s all.

The boss gave us a blanket and a campsheet to keep the rain away. We got very low wages. They had a shop at Kurundi and that used to take half our wages straight away.

So in 1977 we walked off Kurundi. We walked off easy way. We knew what was coming, this land rights law was coming, so we just walked off quietly. A good mob of us walked off with our families. We were sitting down over there at a place called Ngurrutiji.

We stopped there when we come away from Kurundi station. In 1985 we bought this McLaren Creek station and you know when I first came to this place there was nothing. No cattle, nothing. Just place.

That was three years ago. No horses for riding, nothing. We came here with a Toyota and looked around, “where’s the horses?” No horses to ride. “Where’s the cattle?” No cattle, nothing. We had the old truck here from the station (prior owners) but one day they came up and took it away. So I looked all over for cattle.

We were just doing it the Aboriginal way, my old way. We’re horsemen. I also use the Toyota, the bull bar on the Toyota. Knock him down with the bull bar, tie him up with rope. Tie up the front legs and the back legs and let him lie down. Then we go and get the pen, put up a yard and let him stand. The helicopter, we’ve seen it a lot of times. It rounds them up ok, but they die later from too much galloping. The helicopter scares them.

I’ve seen them kill too many. We’re not helicopter men, we’re horsemen. Now we claim this country because it’s our father’s country. We’ve been working on stations all our life, working for someone else.

Now we can work for ourselves.

I’ve been working hard, battling for something. Getting our land back means we can carry on and our children can carry on after us. That’s the way we want it – to look after everything and do a good job.

We’ve got a good few cattle here now. We’ve been grow them up all the way, nearly 200 head of cattle.

We had a meeting and they picked me to be the manager because I understand cattle. We’ve got to do all this fencing around the paddocks now and clean it up and fix the bores then go and look for cattle again. You know, you can’t do all that in one day.

Chilla Well win to traditional owners

Land Rights News – Vol 2 No.10 (Sep 1988)

The Federal Court dismissed an appeal by the NT Government against a land grant to the traditional owners of Chilla Well about 400 kms north-west of Alice Springs on the edge of the Tanami Desert. The government had submitted that there was a public road on the claim area. The Land Rights Act prevents claims over public roads.

The Chilla Well road was a graded dirt track, made especially to take a water drill to an Aboriginal outstation at Mt Theo. Less than 10 kms of the track fell within the claim area. Federal Court Justice Wilcox dismissed the NT Government appeal, saying its grounds were ‘inappropriate’.

Then CLC Director Pat Dodson cited the case as the latest in a long line of failed NT appeals against land claims ‘on the flimsiest of grounds.’

‘The Territory Government is flexing whatever muscle it has to deny justice to Aboriginal people through what can only be seen as an abuse of the judicial process,’ Mr Dodson said.

He said the government was gaining a reputation as a vexatious litigant, and should modify its approach to co-operate with Aboriginal organisations.

NT Attorney General Daryl Manzie responded that the CLC itself had lodged appeals in land claim cases, and that the government supported ’the concept’ of land rights.

Mr Dodson pointed out the NT Government must represent the interests of all Territorians, ‘but conveniently forgets about its Aboriginal constituency.’

‘It really represents the powerful interests of pastoralists and business,’ Mr Dodson said.

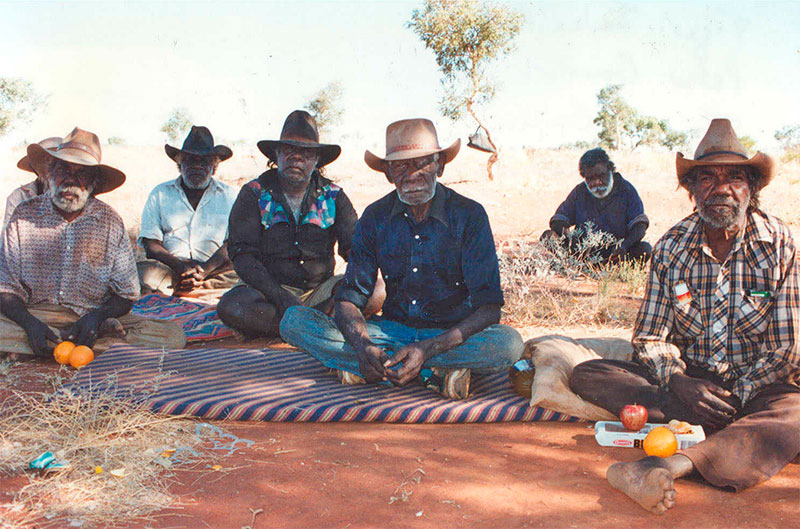

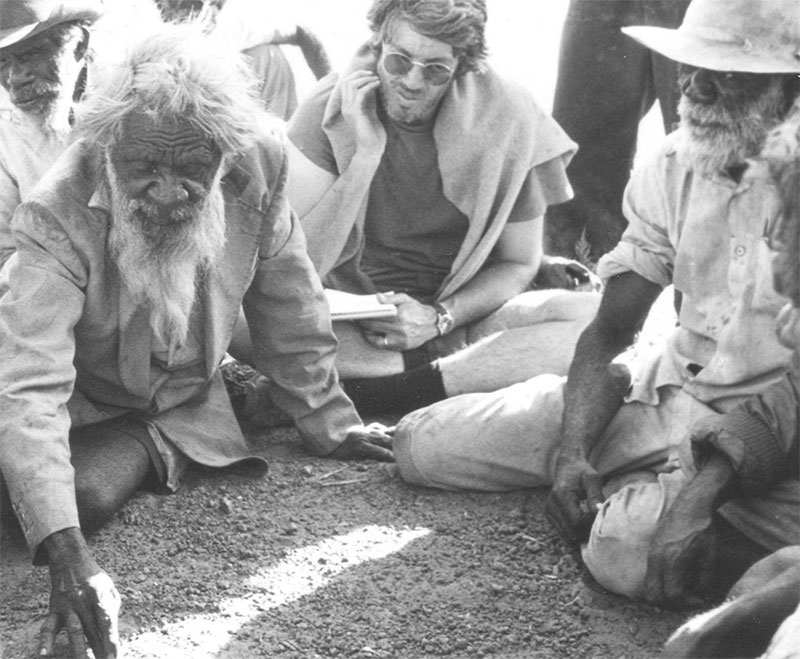

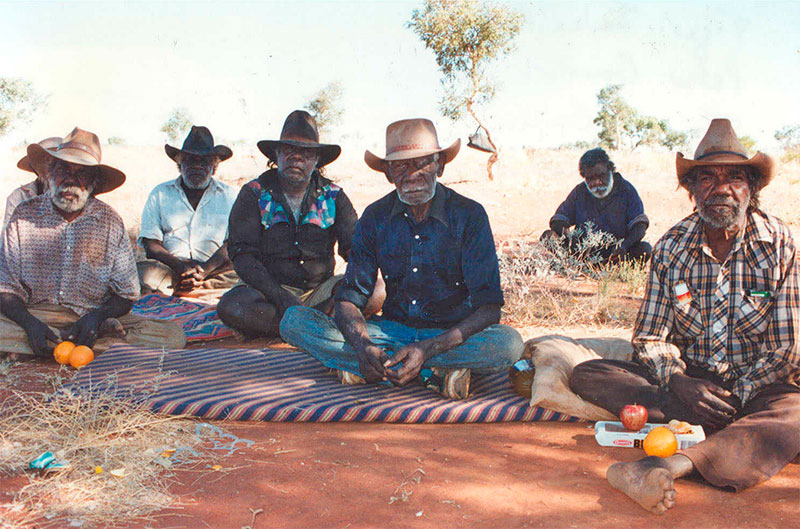

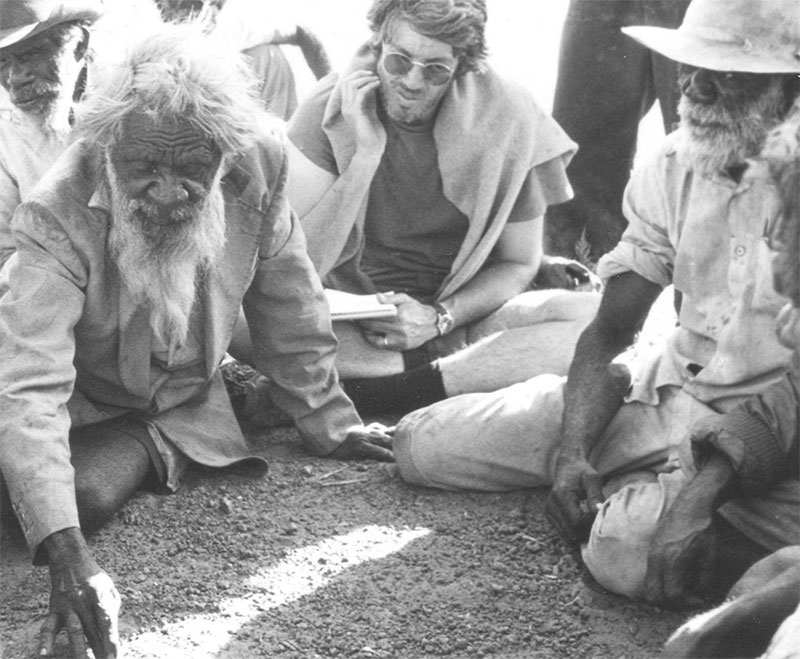

Warlpiri, Kukatja and Ngarti land claim

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.2 (Mar 1987)

The Warlpiri, Kakatja and Ngarti land claim was the eleventh presented by the CLC under the Land Rights Act on behalf of traditional owners. In all land claims, the presentation of the case before the Aboriginal Land Commissioner was the culmination of a long process of CLC research into and consultation with the traditional owners of the land. It was for the Land Commissioner to consider the evidence presented, and other relevant matters, and decide whether or not to grant the land.

This claim was to approximately 2,000 square kilometres of land, bounded on the north by the southern boundary of Tanami Downs pastoral lease (formerly Mongrel Downs, now Mangkururrpa Aboriginal Land Trust), on the east by a line extending south from the Tanami Downs eastern boundary, on the west by the NT-Western Australia border and on the south by the Warlpiri Aboriginal Land Trust.

Linguistically, the traditional owners describe the claim area as ‘mix-up’ as it includes land associated with the Ngarti, Warlpiri, and Kukatja language groups or subgroups.

The Land Commissioner had the privilege of having songs about the Wirntiki sung to him by the claimants on their country, and its ceremonial importance demonstrated in a dance for one of the Wirntiki sites.

On the request of the claimants, further details of the Wirntiki dreaming were provided at a restricted hearing on the claim area.

The benefits of a grant of such remote desert land are difficult for non-Aboriginal people to appreciate. But at base, claim success means secure tenure for many traditional owners of the land, control over the country of their ancestors and a foundation for the ongoing integrity of their culture, as strongly linked to the land as that is.

Mt Barkly land claim

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.2 (Mar 1987)

The Mt Barkly claim was the first time Aboriginal people had used the Land Rights Act to claim a previously purchased pastoral lease, necessary to convert the lease to Aboriginal freehold title.

Some 2,590 square kilometres 360 kilometres north-west of Alice Springs, Mt Barkly is of great religious significance and economic importance to the people from there and nearby Willowra, and to their relatives dispersed around the communities of Ti-Tree, Anningie, Mount Allan, Yuendumu, Alekarenge, and Lajamanu.

People from these places regularly perform ceremonies connected with sites at Mt Barkly.

This is land they have traditionally owned for thousands of years, land stolen from them and upon which boundaries artificial to them were placed for pastoralism.

In 1928, conflict between whites and Aboriginal people over use of land and water in the area culminated in the death of many relatives of the Mt Barkly claimants in the Coniston massacre.

Massacre survivors fled the area, and didn’t return for many years. When they did, many were exploited to develop the pastoral industry.

The Mt Barkly pastoral lease was purchased by the Aboriginal-owned Willowra Pastoral Company early in 1981 with its own resources, without government assistance.

A feasibility study by the Aboriginal Development Commission found it had marginal viability as a cattle station. But while it was always planned to run some cattle there, the principal motivation in acquiring the property was to enable the traditional owners to have free access to their country for hunting, gathering, sacred site maintenance and other economic, social and religious activities essential to their way of life.

Traditional land ownership here and elsewhere is fundamentally a religious relationship between people and land. It is these religious links that give certain rights, namely to use resources of the area, and responsibilities to look after the country including through the ritual performances.

Thankfully, the NT government did not challenge the traditional ownership of Mt Barkly. Yet evidence of it still had to be presented at the hearing. Taking the evidence of the male traditional owners began by them visiting a site with the Aboriginal Land Commissioner.

Women then performed ceremonies for Pawu (Mt Barkly) and Ngarnka (Mt Leichhardt). For two days at Willowra the claimants told of their deep spiritual relationships to the land.

They talked of the dreamings for the traditional countries or estates that constitute the claim area, dreamings that trace their religious links to the land.

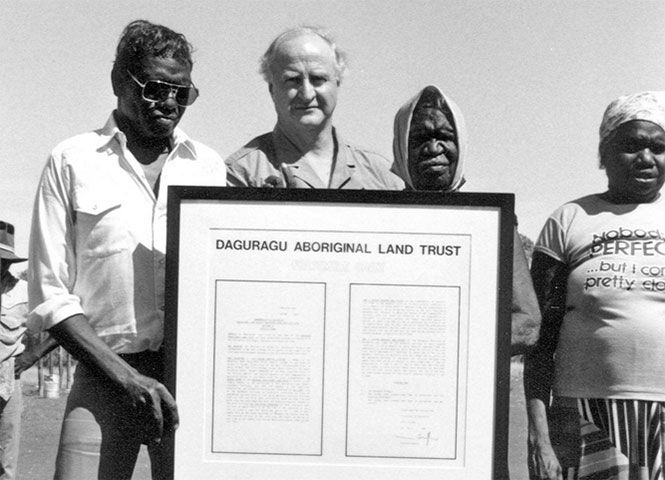

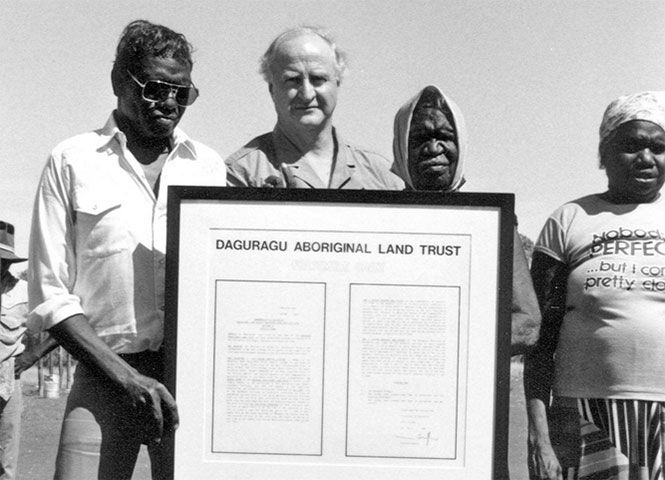

Daguragu station land claim

Land Rights News – Vol 2, No.2 (Nov 1986)

The courageous actions of the Gurindji people in their demand for land rights took the realities of decades of oppression of and colonial injustice to Aboriginal people into the sitting rooms of urban Australia.

Many heard and saw on television for the first time Aboriginal people telling of their exploitation by the pastoral industry.

When the Gurindji stockmen of Wave Hill station walked off the job in 1966, and refused to be bribed back until they got justice through land rights, even politicians were forced to listen.

The indifference of generations of non-Aboriginal Australians was shattered. Aboriginal activists from around Australia kept up the momentum, erecting an Aboriginal tent embassy on the lawns outside national parliament house.

The Australian Labor Party – under the leadership of Gough Whitlam – and the trade union movement responded and land rights became a central part of Whitlam’s successful drive to wrest Government from the Liberal/Country Party Coalition for the first time in twenty three years.

In 1974, Prime Minister Whitlam handed the Gurindji a lease to part of the vast Wave Hill property, operated by Vesteys, a British-based multinational company. Gurindji elder Vincent Lingiari said at the time: “They took our country away from us, now they have brought it back to us ceremonially.”

It was a great and symbolic day for Aboriginal people and their supporters around Australia, but to the Gurindji it was only a first step.

Whitlam echoed this when he said that the lease ceremony was “a token that these lands will be in the possession of you and your children forever.” The Gurindji wanted perpetual title, under the foreshadowed Land Rights Act. They feared that without this governments could take away their lease. This fear was realised in 1979 when the NT government gave notice to surrender the title.

In May 1986, twenty years after the walk-off, the Gurindji’s demand for justice through land rights was finally met, and the Hawke Labor government’s Minister for Aboriginal Affairs Clyde Holding at last handed to them the deed to inalienable Aboriginal freehold title under the Land Rights Act.

Yet this final achievement was marred by other threats to the desire of the Gurindji – and other Aboriginal people – for control over their land and lives. The Gurindji were deeply worried about the presence of the NT government-sponsored town of Kalkaringi.

They feared they would become fringe dwellers here, almost on their own land. Most of all, they want the school moved into their community, on the Aboriginal land now surrounding Kalkaringi.

Worse were plans being considered to allow the NT government to effectively repeat Kalkaringi by giving the government the power to acquire portions of Aboriginal land for any ‘public’ purpose.

The Gurindji were aware too that at the time of the return of their land the Hawke government was moving to put an end to provision in the Land Rights Act for the conversion of pastoral leases to Aboriginal freehold title.

Fortunately such damaging changes to the act were rejected, facilitating secure land rights, including for other Aboriginal owners of cattle stations.

Uluru—Kata Tjuta land claim

Land Rights News – Vol 2 N.1 (Nov 1985)

In November 1983, Labor Prime Minister Bob Hawke announced that Uluru—Kata Tjuta National Park would be returned to its traditional owners. This was land that the Aboriginal Land Commissioner could not recommend for grant under the Land Rights Act because it had already been alienated as a national park.

With the Prime Minister’s intervention, it would become inalienable freehold Aboriginal land on the condition that it be leased back to the Commonwealth as a national park. A joint-management scheme was instituted so that the continued use of the park as a tourist venue was assured. An Aboriginal majority on this board was negotiated and enshrined.

Prime Minister Hawke’s announcement succeeded a previous undertaking by then NT Chief Minister Paul Everingham in 1982 to grant NT title to the iconic landmark of Uluru.

The traditional owners preferred title under the Land Rights Act, a stronger title than any proposed by the NT government. Federal Labor’s move led the NT Everingham government to use Uluru and its traditional owners as political pawns in the Territory tradition of Canberra bashing.

Uluru—Kata Tjuta is of course no stranger to conflict.

The Aboriginal Land Commissioner Justice Toohey commented in a report. “The history of black and white contact from the 1870’s onwards is like that of many other parts of this country. There is evidence of cattle killing by Aboriginals and some attacks on whites with a consequent over-reaction by police and pastoralists.”

For instance: “In 1934, while investigating the death of a young Aboriginal man near Atila (Mt Conner), the police arrested several men who later escaped and made their way to Uluru. There they hid at Mutitjulu but were found. One, a brother of Paddy Uluru, tried to escape and was shot. The death is still in people’s minds.

“I have no doubt that the conflict (between black and white) that did exist, in particular the punitive expeditions, caused people to move away from actual or potential trouble.”

Freehold title to and joint management of Uluru—Kata Tjuta now gives them good reason to return.